Photo: Stella Olivier

Sybil capped the whole season-long of Kentridge Residency at UC Berkeley, “a rare opportunity to engage directly with Kentridge and his artistry via lectures, performances, and events showcasing the breadth and depth of his creative output.” That Friday performance was also celebrated as the Cal Performances’ 2023 Gala, honoring Kentridge and supporting their mission “to produce and present performances of the highest artistic quality, enhanced by programs that explore compelling intersections of education and the performing arts.”

Sibyl was conceived as two-part; the 22-minute film with live score The Moment Has Gone, followed (after intermission) by the 42-minute chamber opera Waiting for the Sybil. The latter was originally commissioned by Teatro dell’Opera di Roma to create a “companion piece” for its 50th anniversary revival of Alexander Calder’s Work in Progress, a seminal “ballet” (as Calder called it) featuring an array of mobiles, cyclists, and large painted backdrops combined with a soundtrack of avant-garde electronic music by Niccolò Castiglioni, Aldo Clementi and Bruno Maderna.

A portion of Work in Progress (without the soundtrack) can be viewed below. Waiting for the Sybil (together with Work in Progress) was premiered at Teatro Costanzi on September 10, 2019, to mark its autumn opening.

The inspiration for Waiting for the Sybil came from both Calder’s work and the Ancient Greek mythology of sybils (oracles), as Kentridge himself described. After realizing that it was possible to tour with Work in Progress due to the logistics of transporting Calder’s props, Kentridge decided to pair Waiting for the Sybil with an expanded version of a film he was making at that time called City Deep, accompanied by live score from Mahlangu and Shepherd. That became The Moment Has Gone, the first part of the collective work that Kentridge called simply Sybil.

The piece received its world premiere in London’s Barbican Theatre on April 22 last year, before traveling to Ruhrfestspiele in Recklinghausen and Théâtre du Châtelet. At the time of the premiere, The New York Times wrote an illuminating article about Sybil, including this quote from Kentridge: “A libretto is a straitjacket: You put it on willingly, but nonetheless it is a restriction. This is a totally different experience.”

Nothing could have prepared me for the extravagant sensory overload that I experienced last Friday, as Sybil represented a full-blown attack on the senses! Not only it engaged the audience visually and aurally, but it also provided them with food for thought long after the performance was over. Furthermore, it invited the audience (like me) to research and learn more about the meaning and symbolisms of the work; a perfect representation of art as a medium of social change!

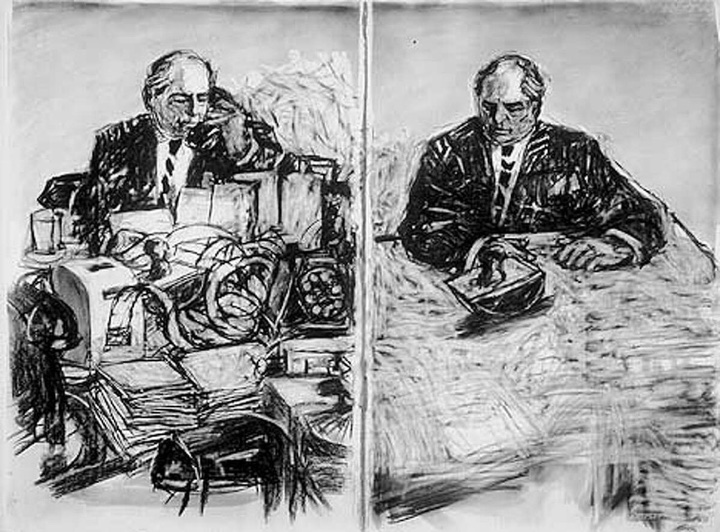

The Moment Has Gone started simply enough, as Kentridge himself appeared in the video drawing on a blank canvas. With his well-known “unique charcoal animation technique of successive erasure and redrawing” he then conjured his alter ego, the fictional mining tycoon Soho Eckstein (the subject of many of his drawings (aka The Soho Eckstein Cycle)), and set the motion rolling with the juxtaposition of Eckstein in an art museum with a solitary miner persistently digging at a mine, highlighting the social injustice in South Africa as they moved from Apartheid to a democracy. Kentridge framed that “storyline” with images (not just one, but two!) of him in the studio drawing those scenes, no doubt to signify the act of the creation of art.

© William Kentridge

For The Moment Has Gone, Mahlagu used an all-male isicathamiya style, which he called in an interview with Thomas May a “suppressed” form of singing “to steal a moment of joy when you have been removed from your homeland and put in places where noise is not allowed by white people”—to create a haunting soundscape, signifying the important of the message to be relayed. I only wished that Kentridge restrained himself from appearing double in the video, as those moments (which attracted unnecessary laughter from the audience) somehow lessened the impact of such complex storytelling!

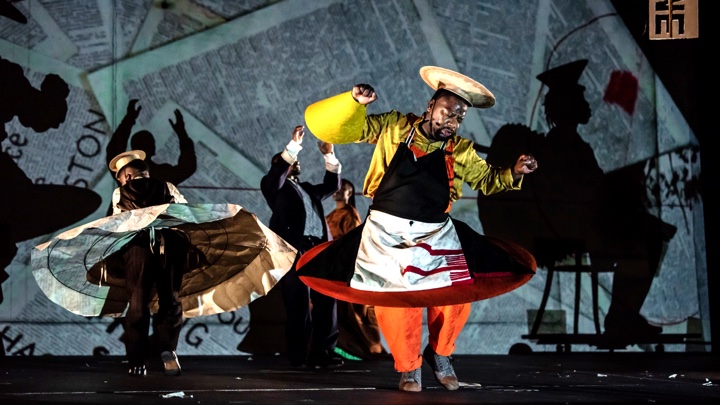

While The Moment Has Gone reveled in its monochromatic glory (except for those scenes with Kentridge in studio), the 9-performers Waiting for the Sybil exploded in kaleidoscopic colors right from the moment the curtain opened, thanks to Greta Goiris’ vibrant costumes and Sabine Theuissen’s lively sets. The whole experience could certainly be described as “organized chaos,” well-fitting the source of its inspiration, and Kentridge truly employed every aspect of his practice into it; from projection, charcoal animation, dance, props, all the way to shadow movement.

In a way, he embodied the spirit of Caldera’s Work in Progress, as the six scenes of Waiting for the Sybil moved with relentless force, including the front curtain that was used to delineate those scenes. Kentridge used such transition mostly to project a hand-drawn swirling oak trees and leaves (upon which Cumaean Sybil wrote her prophecies).

The choice for eschewing a linear libretto really established the uncertainty nature of fate and the irony of the unrelenting desire to know one’s fate. Kentridge filled the backdrop with unrelated quotes to depict the Sybil’s questioner’s fate, ranging from silly “Resist the third martini” to the mysterious “Heaven is talking in foreign tongue” or morbid (especially in times of pandemic) “Fresh graves are everywhere”.

During the “Starve the Algorithm” scene, those sayings were even verbally spoken (through the use of a megaphone) to suggest to the audience a cryptic or ominous feeling about their meanings!

Initially I was a bit disappointed as from my seat in Right Mezzanine I could only see half of those texts projected on the screen (as they were blocked by the thick black panel framing the stage). However, my disappointment dissipated as I realized that there was no particular significance to those wordings, certainly not above the actions of the performers!

Speaking of the nine performers, they worked closely as a tight ensemble to present the six scenes as moving tableaus. Generally, the six scenes could be characterized as follows. The first scene established the Sybil, in the form of dancer Teresa Phuti Mojela in brown dress dancing frantically (recalling the Oracle from Zack Snyder’s epic historical action film 300), while the next scene placed the action of disseminating Sybil’s fates in a warehouse, where one typed the fates with a typewriter, and another interpreted the papers by listening closely to them.

The third scene was where Calder’s influence manifested, as everyone on stage swirled in a circular motion to resemble the wheel of fate, followed by the aforementioned “Starve the Algorithm” scene. The fifth (the chair dance) was probably my most favorite, as it depicted the unpredictable nature of fate … just when you thought you had everything figured out, your life (as symbolized by the chair) fell apart! The final scene illustrated the persistence of human being in search of their fate, even if the Sybil was visibly exhausted and slowed down in her dance.

Musically, Mahlangu and Shepherd brought a vast range of musical influences to the score of Waiting for the Sybil, drawing strength from their experiences as choral composer (Mahlangu) and jazz pianist (Shepherd). In the May interview linked above, Mahlangu observed “I bring the traditional and the visceral and Kyle Shepherd brings the classical and the technical.” The collaboration gave Sybil a rich sonorous score with an underlying lamentation and a hint of hope—exactly like our fate!

Kentridge also talked about the algorithm, the contemporary version of fate we wanted to control but ending up controlling us. In the era of ChatGPT and the likes, it is worth to note that this so-called philosophical algorithm may soon become a reality, and Sybil served a perfect reminder of how we humans should behave before our existence made redundant!

Sybil will travel next to Madrid next and I assume, it will visit more venues afterwards. If you can, you would be wise to try to catch a performance of it, as it remains a staggeringly profound meditation of life and fate, and I guarantee that you would come out of it examining the meaning of life and what’s important to you. Truly a life-changing work!

Comments