But beyond the opera’s ingrained pomp, however, one wonders why this work – so unrewardingly ambitious, so difficult to cast, so affectively weird — was chosen for this festive occasion. Surely it was not to feature one singer in particular; the afternoon’s highest profile performer, bass Morris Robinson, was fêted at length onstage for the 25th anniversary of his BLO debut but hardly shown off to any great lengths in the smallish role of Ramfis. (Falstaff, albeit an unconventional one, would have been a better and more à propos choice for this bunch.) And surely not as some sort of culmination or commentary surrounding BLO’s much touted engagement initiatives concerning the matters of politics or representation that fully encompass Aïda’s baggage – in fact, predictably (and lamentably) sanitized subtitles and a mea culpa program note by Anne Bogart here were the extent of the grappling with the issues that animated last season’s courageous and fully staged Madama Butterfly. Nor was it an opportunity for Music Director David Angus to wade into philological debates, the only changes made to the score being the excision of any dance music. And they couldn’t have known when selecting the opera last year how demoralized and fatigued we’d all be of talking about loud and brassy theocracies by the end of this week.

But Aïda they chose, so it was love and intrigue in the shadow of the pyramids we got. But it was an Aïda that often worked harder rather than smarter, its celebratory purpose often dragged below the surface of Verdi’s gurgling Nile despite good intentions.

Nobody seemed more well intentioned than soprano Michelle Johnson in the title role, but her vibrant dramatic involvement couldn’t redeem such a thoroughly uncoordinated vocal performance. Her main repertoire consists of later works (Tosca, Mimì, Turandot, Bess etc.) that subject the vocal line to less exposure, but she’s no stranger to Aïda which was what made Sunday’s clucky performance in part so disconcerting. The tessitura doesn’t exceed her abilities (though the C of “O patria mia” was practically physically hurdled into), but the full-scale lack of any sort of legato, of any inclination towards an artful negotiation between registers and textures which make this perpetually anguished character just barely more than a cipher, made for tedious listening.

More than in any other Verdi opera, the music for both female protagonists — concentrated around register breaks — derives most of its visceral impact from the anticipation of where a note will come from in the voice and what that shading will bring to a line, not if it will merely be audible or healthy-sounding. Everyone in this opera is always judging, fuming, fretting, hedging, lying; Verdi keeps us guessing by obliging singers to differentiate how those very interior emotions sound externally, which is no easy assignment. That sense of anticipatory drive, however, presupposes a vocal security that was absent here.

A similar sense of ambivalence characterized Alice Chung’s Amneris; she came into her own in the Judgement Scene which elicited the afternoon’s strongest applause, but the rest of the role would have benefitted from the histrionic attention she lavished on that moment. Up to that point (despite what her gowns might have you believe), it had been a performance practically free of chest voice, the music massaged into her smooth and sweet middle voice, and without a trace of imperiousness in her handling of the text. Dramatic mezzo repertoire is perhaps not temperamentally intuitive for this singer, but the raw materials are not without promise.

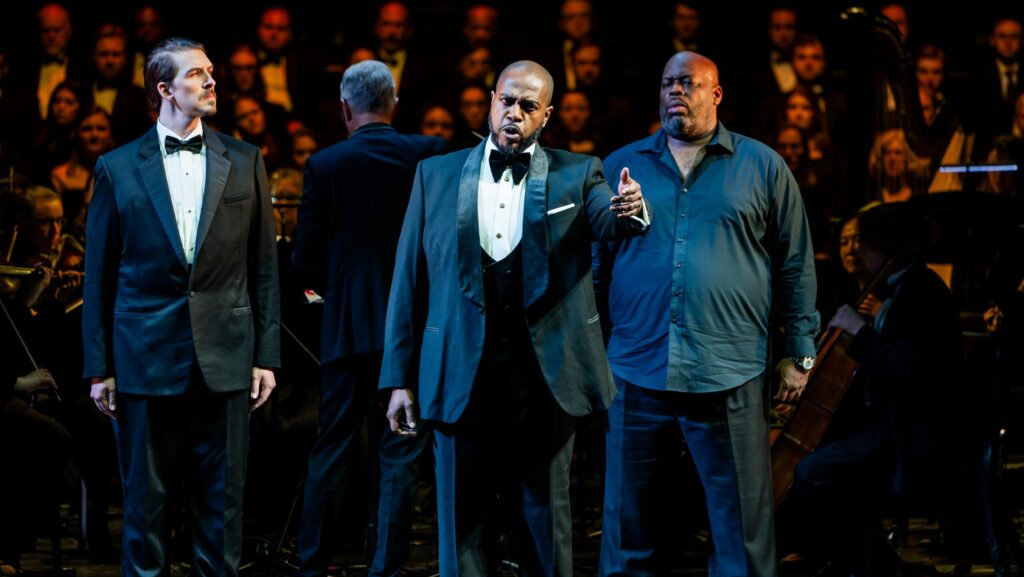

Tenor Diego Torre as Radames was more consistent, singing with both more of a vocal core and genuine squillo. But even his “Celeste Aïda” had an ungainly wavering towards the top (the lilting Fs, not the concluding, robust B-flat) that betrayed more a lack of style than a lack of ability. Only in some of the lower male voices did the elements come to coalesce on a more steady basis; Robinson, the afternoon’s honoree, has an authoritative ease with text if a slightly unfocused overall sound and Brian Major, a real singing actor with a bright and even-tempered baritone, provided a much needed jolt in his Act II arrival as Amonasro.

David Angus valiantly marshalled the choral and orchestral forces with uniformity and verve; despite some seriously problematic sharp playing in the principal trumpets, the orchestra made a fine and cohesive sound and the combined forces of the Boston Lyric Opera Chorus and the Back Bay Chorale were formidable, especially during the Triumphal Scene (which was briefly paused midway through while a chorister underwent a medical emergency onstage – she was stabilized shortly thereafter). Nathan Troup had the off-book soloists moving through a semi-staging in gala attire with fluidity and while the vaguely Futurist scene-setting projections by Jeff Grantz of Illuminus didn’t make much sense, the projections on the wall of the theater during the Triumphal Scene earned their oohs and ahhs.

Not that Aïda is a remotely easy piece to perform, but nearly everything about this performance felt like more work than it needed to be. Perhaps the hubristic choice of opera was one of the inevitable curatorial growing pains that the hand of new Artistic Director Nina Yoshida Nelsen might steady when she begins planning her own seasons in earnest. But overshadowing the afternoon was the unfortunate irony that this performance benefitting community programs (anchored in the newly opened Opera + Community Studios) was itself unable to actually offer an artistically sound genuine article towards which people might eventually be educated. I previously looked at BLO’s opera-void spring season with some sadness — only a Sarah Ruhl/Vivaldi mashup starring Anthony Roth Costanzo as well as a production of Carousel remain. After Sunday, I think this time out might be necessary.

Photos: Nile Scott Studios