It quickly sold out bringing in the younger and more diverse audiences that most performing arts institutions desperately court and crave.

This critic was seeing this work for the first time and found it a moving and provocative experience in the theater. There are weak parts in the work (unmemorable declamatory vocal melodies, repetitive sections that keep heavy handedly recurring, overdependence on monologues with a paucity of vocal duets and ensembles). But the combination of the fluid staging by James Robinson and Camille A. Brown, strong conducting by Evan Rogister and pivotal and compelling central characterizations by Ryan Speedo Green and Latonia Moore made for a powerful evening of musical theater.

Working from the memoir by journalist Charles M. Blow, librettist Kasi Lemmons keeps the focus not so much on the external conflict but the internal conflicts of the protagonist. The actions of others wound the soul and impact the development of Char’es Baby (Ethan Joseph) as he matures into the emotionally shut down, angry, sexually conflicted and self-hating teenage (later adult) Charles (Speedo Green). The opera’s protagonist must decide whether to be the victim or take revenge or let go – almost a Hamlet figure. The homosexual urges the protagonist is suppressing (Blow came out as bisexual at the age of 44 after divorcing his wife with whom he fathered three children) are hinted at but not explicitly dramatized except in a “dream ballet” (choreography by Camille A. Brown) showing men of color physically exploring each other’s bodies.

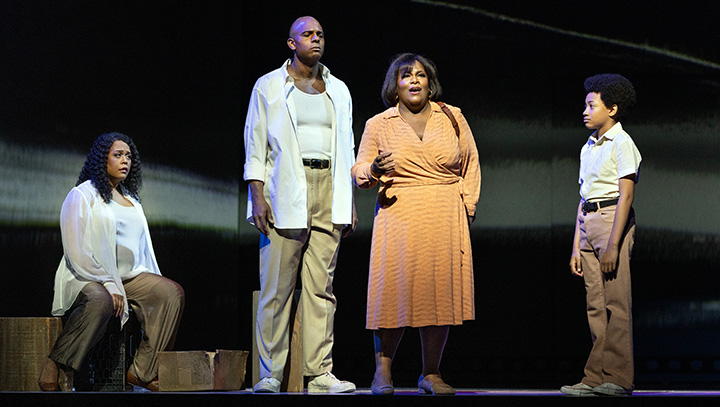

The traumatic experience that haunts the younger Charles is sexual abuse at age seven by his older cousin Chester (Daniel Rich in a smoothly sung and powerfully manipulative performance). Damaged emotionally by this experience, Charles keeps seeking love from others including his exhausted and withholding mother Billie (Moore repeating her triumphant performance from the Met’s original production) and later various women including university student Greta (Brittany Renee). Renee also doubles as personifications of Destiny and Loneliness who haunt Charles throughout the story trying to influence his actions.

Both Green and Renee appeared in the original production in supporting roles – Green as Uncle Paul (now strongly sung by Kevin Short) and Brittany Renee charmed as the alluring Evelyn, Charles’ first girlfriend (now Kearstin Piper Brown in a winning Met debut). In the tripartite role of Destiny/Loneliness/Greta, Renee initially made an equivocal impression – her upper register gleams and soars but her middle register is comparatively small and weak. Initially, she lacked the vocal authority and Met-sized instrument that the role’s originator, Angel Blue, possesses. She came into her own in the role of Greta, revealing a mixture of longing and desire mixed with unease as her character realizes the extent of Charles’ damage and aching need which she can’t heal or fulfill.

Ryan Speedo Green has a totally different voice and stage presence from Will Liverman, who scored in the lead role in 2021. Green has a bass-baritone voice that is deeper, darker (often hooded in tone) and much louder than Liverman’s. It is likely that Blanchard lowered the role for Green’s bass-baritone as he did for the higher baritone lead role of Emile Griffiths in his Champion last season. Physically and vocally Green is an imposing figure – easily believable as a college basketball player with his height and muscular frame. The voice vibrates with palpable emotional conflict and anguish – yet his diction was consistently clear. This Charles is very much an adult male, not a hurt man-child, whose potential for violence and self-destruction are as great as the emotional pain and vulnerability that drives him. Speedo Green’s more overt masculinity made Charles’ sexual ambiguity and fragile inner self more in contrast and in conflict with his powerful virile external persona.

Veteran Latonia Moore, her compromised soprano in strong form, sometimes sounded hollow and breathy in the middle but rose to powerful climaxes as Billie, Charles’ loving but often neglectful mother. She seemed the most comfortable in the jazz-classical hybrid idiom having studied jazz singing in college before transitioning into opera. Moore was a rock of emotional truth, her presence commanding center stage throughout as she confronted her adulterous husband Spinner (a smooth and sleazy Chauncey Packer) with a pistol, provided the glue that kept her five sons out of hunger and trouble, and later revealed her deep maternal love for Charles.

Allen Moyer’s movable unit sets were transformed into endless variety by Greg Emetaz’s evocative, never distracting projections and Christopher Ekerlind’s often bold lighting. Brown’s choreography in Act II stopped the show with the homoerotic “dream ballet” and dancing Grambling frat boys. Rogister, a specialist in tricky “modern” (complex 20thcentury) scores, seamlessly synthesized the jazz, blues and modern classical elements of Blanchard’s idiom.

Blanchard, Lemmons, Robinson, Brown and Blow himself (embracing his onstage counterpart Green) all appeared at the final curtain call before an enthusiastic audience in a genuine standing ovation which extended to the upper balconies and side boxes. Whether the work attracts as much public attention and box office clout in revival is an open question – but the live audience got the work’s message.

Photo: Marty Sohl / Met Opera

Comments