… perhaps not in the top 10, but definitely somewhere in the top 20. For some time, I have been itching to do one of my exposés on it, but have been put off not only by committing myself to listening to it so many times, but by knowing that I will then have to put up with a bloodbath from those that think that either The Greekess or Mme. Kunc should be in the #1 spot when clearly La Sublima is. Be that as it may, what motivates me to write now is the upcoming performances at the Salzburg Easter Festival with a cast that could possibly equal the legendary ones of the past: Anna Netrebko, Jonas Kaufmann, and Luca Salsi (well, maybe not Salsi) under the baton of Antonio Pappano. Here are a few thoughts.

The composer Ponchielli … it’s hard to understand how someone could compose so much inspired melodic music, including some of the most famous music ever written, “The Dance of the Hours,” and then not have written anything of consequence ever again. It’s hard not to picture the crocodiles and tutu-wearing hippopotamuses of Disney’s Fantasia, much less start singing “Hello Muddah, Hello Fadduh.” But despite the tune’s wide recognition, just how many people could identify “The Dance of the Hours” by title or composer?

If I were to categorize Gioconda with similar operas, it could fall into several categories, such as “Operas that Critics Love to Hate” or just simply “Grand Operas” (which is pretty much the same thing). Perhaps “One-Up” operas, i.e., operas like Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci or Adriana Lecouvreur or Andrea Chenier, all of which are more or less the singular operas of note by the composers that wrote them (which again puts them pretty much into the same thing as the first category). It is a peculiar opera in that it’s hard to determine to what period it belongs. First performed in 1876, it is effectively the last of the great Grand Operas, the genre of 19th-century opera with its specific rules: four or five acts, a ballet (not too early in the evening), large-scale casts and orchestras, lavish sets and costumes, spectacular effects, and plots usually revolving around some historical event. The period of Grand Opera lasted from around the 1820s to the 1860s. One could claim that Gioconda logically follows the heyday of Meyerbeer, the King of Grand Opera, whose last opera, L’Africaine, was first performed in 1865. Gioconda’s 1876 is also five years after the premiere of Aïda, yet for the most part it sounds more similar to the Verdi of the 1860s. Gioconda also foreshadows the verismo period (I suppose that depends on how it’s performed). Clearly, La Gioconda is one of a kind.

Detractors have dubbed the opera vulgar, yet its supposed vulgarity is what has made for its durability. Think: demented – and if you don’t understand that reference than you sorely need to read Ethan Mordden’s book Demented (currently available on Amazon for 96¢). The opera lacks any intellectual poses or mystical preaching. The object sought and achieved is emotional communication at a very basic level – the definition of verismo. An influential critic in Rome, when forced to see a performance of Gioconda without the slightest desire to do so, wrote, “It is impossible to understand how this opera that has been called a musical aberration is still performed in this year of 1933 before a public whose taste, we ventured to hope, is superior to that of Ponchielli.”

Nevertheless, La Gioconda is the quintessential grand opera. It demands six voices of superstar power and those six characters supply the archetypal opera plot: The contralto is the mother of the soprano and murdered by the baritone who is in love with the soprano, who’s in love with the tenor, who’s in love with the mezzo, who is married to the bass. It is filled with spectacular Venetian scenery: the Piazza San Marco, a ship that blows up, and the Ca’ d’Oro where that most famous of opera ballets takes place. Each character has a terrific solo moment though I’ve always found it peculiar that Gioconda herself is a street singer who never gets to sing a street song; her big aria near the end of the evening is about suicide, hardly the subject for a street song. Ironically, “la gioconda” – not to be confused with Leonardo da Vinci’s painting – is Italian for “the happy woman.” The plot is filled with exciting moments involving blackmail, adultery, religion, the aforementioned blowing up of the ship, attempted murder, and, yes, suicide. Most of it has its own operatic logic though who can explain what the blind La Cieca is doing wandering around a palazzo by herself – oh, that’s right, she has to supply the mezzo voice in the thrilling concertato that ends the third act because the rightful mezzo who is actually on stage is supposedly dead. Ah, Grand Opera!

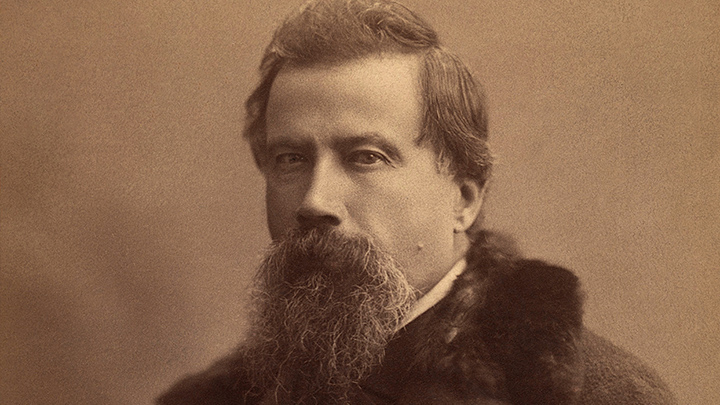

Amilicare Ponchielli

Ponchielli was born in an obscure town, Paderno Fasolaro in the Lombardy region in 1834. An obvious prodigy, he won a scholarship at the age of nine to study music at the Milan Conservatory. He wrote his first symphony when he was 10 years old and his first opera at the age of 22. When he was 19, he graduated with honors but he was unable to fulfill his promise. None of his early operas were particularly successful and he earned his money as an organist, bandmaster, and a teacher while transcribing other composers’ music. Gradually, his operas gathered recognition that brought him a contract with the music publisher Ricordi and La Scala where Gioconda had its very successful premiere on April 8, 1876 – so successful that even the prelude was encored. To his credit, Ponchielli recognized faults in his work and set about correcting them. In all, he made three revisions to the work and it achieved its definitive version in 1879 in Genoa. One revision included a new version of Alvise’s aria that was later discarded and repurposed within Iago’s Credo in Otello. The final version included a magnificent new concertato as the finale for Act III, which was to become one of the opera’s most famous and lauded excerpts. This is the sort of moment for which this kind of opera exists: everyone’s emotions and tensions pulled into a huge ensemble, complex yet dominated by a single memorable theme used to tremendous effect on the final page of the act, when it bursts forth from the orchestra as an ardent summation of the momentous scene.

In 1881, Ponchielli was appointed maestro di cappella of the Bergamo Cathedral and in the same year he became a professor of composition at the Milan Conservatory; among his students were Puccini, Mascagni, and Giordano. In 1874, he married Teresina Brambilla who became a famous interpreter of the role of Gioconda. He died of pneumonia in Milan in 1886.

I thought I should listen to some other Ponchielli opera and came across a performance online of his final opera, Marion Delorme (no, not an opera about Marion Lorne). A lot of it reminded me of Mercadante who would come between Donizetti and Meyerbeer, but by the final act, I could clearly recognize La Gioconda and found it sort of enjoyable. It sounded like Gioconda and Enzo going at it; Marion and Gioconda are definitely cousins. With some effort in trying to find a synopsis, I found a review from Gramophone by Alan Blyth and it’s worth quoting his synopsis:

“Based on a drama by Victor Hugo (source of so many 19th-century libretti), it is far from being the best plotted of operas. Taking place in 1638 France, dominated by Cardinal Richelieu, it concerns that favourite Romantic figure of the good-hearted demi-mondaine, the Marion of the title, who is greatly loved by the youthful, unhappy Didier, who has no idea of her courtesan past in Paris. Eventually he learns about it and of her numerous lovers, among them the devil-may-care Severny (who eventually goes to the stake with Didier, as a punishment for duelling, outlawed by the Cardinal) and the Scarpia-like Laffemas. As with Tosca and Scarpia, Marion agrees to give herself to him to save Didier, all to no avail.”

Now, just how many opera plots can you find here???

La Gioconda is based on 1835 play by Victor Hugo Angelo, tyran de Padoue (“Angelo, Tyrant of Padua”) and modeled the construction after the Grand Opera style of Eugène Scribe, the librettist of many of the most successful grand operas and opéras-comique. The librettist is listed as Tobia Gorrio, an anagram and pseudonym for Arrigo Boito. One might think, and many did, that Boito was ashamed of the text, but there is no proof of that, and he had used that pseudonym as a signature for many articles that he authored. Fresh out of the conservatory, Boito was filled with ideas that were against the musical concepts of conservative Italians. He wished to reform Italian music along the lines of Berlioz and Wagner and turned out theoretical essays that were clearly attacks on Verdi.

The setting of Hugo’s play is Padua in the 16th century. The wicked Angelo (Alvise in the opera) is in control of the city which is overrun by spies; among them is Homodei (Barnaba). Angelo’s mistress is La Tisbe (to become La Gioconda) who’s current profession is an actress-courtesan instead of a ballad singer). As in the opera, Angelo’s wife, Caterina (Laura), is in love with Rodolfo (Enzo). In the final scene, Rodolfo stabs La Tisbe just before he is reunited with Caterina. In general, the events of Hugo’s play are even bloodier than the opera. The play stayed in the repertory for many years and provided a star vehicle for many celebrated French actresses, in particular Sarah Bernhardt.

Ca’ d’Oro – Venice

La Gioconda is like Frenchified melodramma with a Trovatore cast (plus an extra mezzo) and even mirrors Trovatore’s idiotic contrivances of plot. Indeed, the ideal Trovatore cast would be the ideal Gioconda cast. More on that later. The opera acts are titled Act I: La Bocca del Leone (The Lion’s Mouth), Act II: Il Rosario (The Rosary), Act III: Ca’ d’oro (the House of Gold), and Act IV: Il Canal Orfano (The Orfano Canal). The acts respectively – and spectacularly – take place in the Piazza San Marco during Carnivale, on the wharf and deck of Enzo’s ship off an uninhabited island in the Fusina Lagoon, in a chamber and ballroom of the Venetian palazzo along the Grand Canal (later to become a casino and currently a museum — and one vaporetto stop away from the Ca’ Vendramin Calergi where Richard Wagner died), and finally, a crumbling ruin on the island of Giudecca on the Orfano Canal (if a production of Gioconda were to be given in New York City today, it would probably take place on the Gowanus Canal). Not much you need to know about the plot beyond what I wrote up above. For the record though, the story revolves around the street singer Gioconda, devoted to her blind madre adorata La Cieca who is saved by her rival Laura, herself married to wealthy Alvise, head of the Inquisition, though in love with the banished Genoese nobleman Enzo adorato, Gioconda’s ex … oh, yes, the villain: Barnaba, he’s a spy for the Inquisition and hot for Gioconda but she prefers suicidio. And that’s all you need to know about the plot and the characters.

La Gioconda at the Deutsche Oper Berlin

Instead, let’s talk about the music.

Who would think that the operas Mefistofele, La Gioconda, and Otello have anything in common? More than one might think. Boito was the composer and librettist of Mefistofele, the librettist of Verdi’s Otello as well as Falstaff, and under the anagram Tobia Gorrio, the librettist of Gioconda. In my research, I came across a rather curious article by Josmar F. Lopes on an even more curious website, Curtain Going Up (I highly recommend it as there’s a current article, “They Lived for Their Art – The First Ladies of Opera: Callas, Tebaldi, and Milanov (Part One)” – highly relevant to this essay and I’m dying to get to Part Two!). The article is entitled: Similarities between Mefistofele and La Gioconda. I admit that I always find similarities with the Laura-Enzo duet and the Margherita-Faust duet, “Lontano, lontano, lontano.” However, most of the very long article strikes me as far-fetched. You can read it for yourselves. It did reference a review by Alan Blyth in Opera on Record 3 that found similar similarities between Gioconda and Otello which others have found. I hadn’t thought about it much but when I do, I see that the structures of the two operas are very much alike. Obviously, Boito carried something over to Verdi. Gioconda opens with Barnaba’s goading of the crowd over La Cieca’s supposed use of witchcraft while Iago plies Cassio and the crowd with drink. Clearly, Barnaba and Iago are kin (and Scarpia their son). Enzo enters with “Assassini” anticipating Otello’s “Esultate” and Barnaba’s “O monumento” clearly presages Iago’s Credo. And that’s just mostly in Act I. Think about Act III: ballet (assuming the Otello ballet were ever done) followed by the concertato ending the act with Enzo attacking Alvise vis-à-vis Iago’s placing his foot on Otello. Let’s not get started on Tosca and Gioconda! My thought: there are only 88 keys on a piano – just how many tunes can one get out of them?

Gioconda’s success in Italy led to its American premiere at the Metropolitan Opera during its very first season on December 20, 1883, with the same Swedish soprano Christina Nilsson who had opened the Met in Faust. By coincidence, La Gioconda and Boito’s Mefistofele were the major novelties presented during the maiden season. Following that, the German domination of the Metropolitan repertoire did not see Gioconda again until 1904 with Lillian Nordica and Enrico Caruso. In 1909, the opera opened the season with Emmy Destinnas well as Caruso. 1924 saw a new production with Rosa Ponselle and Beniamo Gigli. It remained in the permanent repertoire through 1940 with a rotating cast of performers including Zinka Milanov and Giovanni Martinelli in a legendary 1939 performance. 1945 saw a new production with Stella Roman and debuting Richard Tucker until it was replaced by the Beni Montressor production on the second night at the new Metropolitan Opera House in Lincoln Center with Renata Tebaldi and Franco Corelli. In all, Gioconda has received 287 performances at the Met. As long as there is a soprano capable of singing the title role, it remains in the repertoires throughout Italy and the United States. It is rarely done in England; apparently it is too “bloody” for proper Englishmen!

Be that as it may, what cannot be denied is that the work is a magnificent vehicle for full-blooded, Italianate singing and demands a sextet of supreme vocalists from each of the major vocal categories. Each of them is rewarded with an aria, all of which are part of that singers standard repertoire, most especially the soprano’s “Suicidio,” the tenor’s “Cielo e mar,” and the stunningly beautiful Rosary aria “Voce di donna” of La Cieca. The opera, far more than its one famous ballet in the third act, has wonderful dance music in the first two acts. It features a succession of great melodies – arias, duets, trios, stirring confrontations, and one of the great concertatos. Even the myriad choruses rousing in the first half and when they serve as background music in the third and fourth acts are intricate and rewarding pieces of music in their own right. No matter the situation, the music is always appropriate and sings an emotional truth.

Generally regarded as a soprano vehicle, it should be considered as an ensemble effort. In the character of Gioconda, Ponchielli presents a soprano role of a woman grievously wronged meeting a tragic end. Gioconda, along with Norma and Turandot, ranks among the heaviest in the Italian repertory. It demands both vocal and emotional extremes. To be crude, Gioconda is a ball-buster of a role. Callas approached the role as “just on the border of decent singing.” Zinka declared, “what could Ponchielli have thought when he wrote those jumps?” The singing line taxes the voice; it is extremely long and strenuous, yanking the soprano from one end of the staff in one measure and then up or down to the other end in the next. Switching gears like that is rough and tiring and one has to be equally strong at both ends of the range.

Stylistically, there should be a considerable emphasis on the chest voice: Eileen Farrell famously never used any, Milanov minimally, and Tebaldi carried it up well beyond any natural territory yet she could still descend to a low B-flat in her regular, lush, middle sound without resorting to chest. It is little wonder that sopranos have come to view the role much as actresses viewed that of La Tisbe; once a staple of the Italian and American repertoire, performances have dwindled in recent years. Primary reason? The lack of a capable soprano to handle the title role, though, one could add, all of the roles need to be filled adequately. Yes, there have been divas who could handle the notes and the needed volume, but lacked the style. The last performances of Gioconda at the Met (and that I attended) were in 2008 and only the mezzo Olga Borodina fulfilled the requirements. However, it was the dancer Angel Corella who got most of the applause – overwhelming applause! That’s not how the opera is supposed to go.

Divertissement: As I’ve been writing, running through my mind was a distant Time Magazine article that started with “Sir Rudolf Bing’s Nightmare.”

It’s a fabulous read! As it turns out, it was a cover story – COVER STORY??? in a national magazine??? – when Tebaldi opened the season (1958) in Tosca. There have also been cover stories of Callas and Price and Sills that I recall. I finally found the original article in the Tosca section of one of my scrapbooks. What’s especially interesting is, paragraph-by-paragraph, how quickly things changed. Within a couple of years, all three voices were mostly worn out and Price, Nilsson, and Sutherland arose. Interesting article. Here’s just the first three paragraphs and relevant to this survey:

Rudolf Bing, general manager of New York’s Metropolitan Opera Company, is not given to discussing his dreams, but it has been whispered that he is haunted by a recurring nightmare. In the dream he is Prince Paris, lost atop a papier-mâché Mount Ida on the Met’s stage. He is surrounded by three goddesses who insist that he choose the fairest of them by handing her an apple (Golden Delicious, supplied by Sherry’s Restaurant). The goddesses, of course, are the three reigning sopranos who, season after season, vie for favor at the Met—Zinka Milanov, Maria Meneghini Callas and Renata Tebaldi.

The choice is harrowing. In the dream, Bing hems and haws, but a decision must be made. The three divas’ pet dogs advance on him. Zinka’s spitz, Nickie, growls; Maria’s poodle, Toy, nips at his ankles; and Renata’s poodle, New, crouches to jump. “Choose, choose, choose!” sing the divas, to some nightmare melody that sounds like Alban Berg played backwards.

Bing wakes up, screaming.

Next time, we’ll dive into Bing’s nightmare with a recording survey featuring in-depth looks at the three sopranos who kept him up at night: Zinka Milanov, Renata Tebaldi, and Maria Callas.