Verdi had an eye for male narcissists that would make any TikTok dating-app commentator proud. The men that populate Verdi’s operas are rarely good—at best they are well-intentioned but ineffectual, easily fooled, or too eager to play the martyr, (Gustavo, Alfredo Germont, Ernani,) at worst they are positively malignant, less people than dark stars who destroy everyone in their paths (Giorgio Germont, the Duke of Mantua, Macbeth, and of course, Iago). But the Marquis de Calatrava might take the cake (pun intended, in this production) for most harm done in the least stage-time—he only has to utter a few words to doom his children.

In Mariusz Trelinski’s new production, which premiered at Polish National Opera last year, the action moves to a nonspecific contemporary setting (‘in’ for 2024: nonspecific modern locales) and, as various promotional material states, “makes extensive use of the Met’s turntable.” This turned out to be something of an understatement: it spun almost endlessly, but, to Trelinski’s credit, it had a purpose: its perpetual motion is that same motion that catches characters and real people up in structures that harm them most by remaining invisible.

With this concept, the director shows himself as strong reader of Verdi and makes a real case for forza as a modern parable of the patriarchy. It has what has felt so vanishingly rare in recent new Met productions: a clear take on a classic work and, through some very compelling stagecraft, the dramatic chops to present an argument for the director’s new reading. This alone makes the production worth watching, even if not all of Trelinski’s smaller choices are effective.

Trelinski does slightly force his reading on us; in migrating the opera to a modern setting, the director adjusts some of the plot points to draw a direct connection between patriarchy and the apocalypse. Here, Alvaro’s accidental manslaughter sets off a chain reaction that causes the war whose setting dominates Act III, instead of war arising for unrelated reasons. By Act IV, this conflict has brought the world to near apocalyptic-state; the peasants of the original are now refugees. The war-glorying tarantella in Act III now plays ironically as wounded soldiers limp or wheel themselves on stage. While it occasionally introduces more confusion into an already convoluted plot, these choices reflect an admirable attitude of Treli?ski’s towards classic opera that isn’t afraid to adjust things in big ways. Take as an example, how the opera opens: instead of the famous notes of the “fate” motive in the overture, we first see a visibly-anxious and ball-gowned Leonora outside of a hotel. We hear her take large drags on a cigarette, before steady herself enough to go back inside. As the doors slam, the stage begins to turn and the overture, finally, began as we follow her in. From there, the motion will almost never cease until the show’s bloody conclusion.

It’s a bold choice, given how famous this overture is, and a good one. The initial shiver wore off for a while as the opera started in earnest and for a long time was replaced by skepticism. Something felt a bit off in Acts I and II: musically, it felt choppy and unsettled, losing the propulsive force of Verdi’s orchestra and sometimes obscuring the structure of the vocal lines. There was something of a power struggle going on between Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s conducting and the singers, evidenced by some misplaced breaths and some…disagreements… around tempi and rallentandi. The direction was similarly scattered; sometimes incredibly subtle, but other times whapping us on the nose with its cleverness. The generally strong visual sensibility marred by some rather atrocious projections (which were often out-of-focus, to boot!) whose imagery would have looked better on a laptop screen where it the CGI of it all wouldn’t be quite so visible. As it was, it provoked a lot of unintended chuckling, particularly in Leonora’s vision of the Virgin Mary, who looked like a spooky video game babe. The incursion of this particular visual was all too jarring. It this was a bad night for wigs on the Met stage, too: Leonora’s penitent pixie crop seemed a punishment too severe for her crimes, while Alvaro’s metal-head tresses were dull and stringy like the “before” pictures in a Tresemmé ad. Perhaps he was sneaking in after a show at St. Vitus and got caught waiting for the L train. But what would a night Met be without some tragic wigs?

Lise Davidsen was very strong as Leonora, but she suffered the most from the lumps and bumps of the first two acts. She has a unique voice—powerful and generous with plenty of bite, but little warmth—and perhaps not one perfectly suited to the dramatic needs of Leonora’s character, who must be so instantly sympathetic that her subsequent destruction carries full emotional force. Davidsen sang beautifully in the first two acts, but something did not quite click both with the characterization and with the voice.

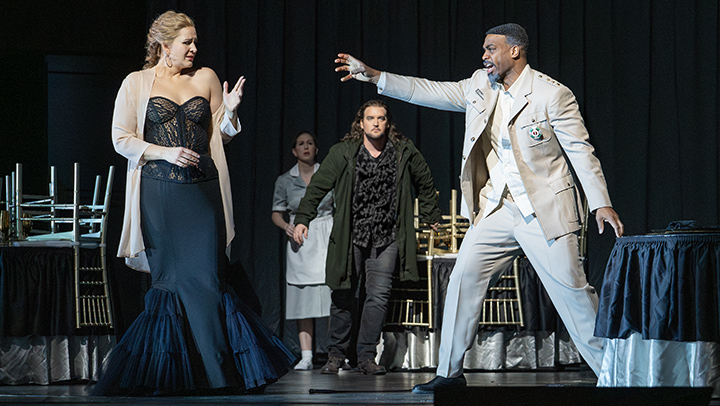

By the first intermission, I felt ready to write this one off as an interesting attempt but without the ability to deliver on its big ideas. But the final two acts pulled off whatever the operatic equivalent of a Hail-Mary pass is and turned my entire opinion around. Here Trelinski’s direction, and his somewhat sea-sickness inducing use of the turntable, yielded such rich dividends that most of the earlier flaws were forgotten. Alvaro’s aria at the beginning Act III marked a musical and dramatic turning point. Nézet-Séguin seemed to breathe more intentionally with his singers, while tenor Brian Jagde poured forth a river of energetic, lustrous sound. The world stopped spinning, finally, and not just because the turntable lay blessedly still for a few moments. Igor Golovatenko, as Carlos, sounded good to start with, but only got better and better as the night wore on. The baritone has a flexible, powerful instrument with a welcome lightness that made the otherwise exhausting character of Carlos (who has only one note: you killed my father, prepare to die) compelling and almost sympathetic. He and Jagde were well matched; their duets were easily the amongst the opera’s most exciting moments.

Boris Kudlicka’s sets, though arresting throughout (think apocalyptic Cabaret), became increasingly dynamic. His set for the fourth act, which took place in the rubble of a bombed-out train station was simply marvelous—intricately textured, realistic, and sinister. Revolving under Marc Heinz’s lights, it shapeshifted with every degree of rotation, catching glimpses of the Marquise’s ghost in a moment of clever staging that revealed this opera as something akin to a horror film. Finally, Trelinski’s direction snapped into place, perfectly melding strong visuals with clear dramatic effect. It was scary good and displayed just how well the Met can do theater when it’s in the right hands.

Similarly, my earlier doubts about Davidsen’s Leonora eased up significantly. When she fourth act, I was able to relax fully into her portrayal. Her “Pace, pace mio Dio” was simply spellbinding; as a now aged-up Leonora, Davidsen’s natural gravitas and dignity aligned with her character, and, with a now-becalmed orchestra beneath her, she allowed a bit of balminess in to her sound, to the audience’s vocal delight. The applause was so thunderous that Davidsen momentarily broke character to incline her head.

The whole cast fared well, especially in the latter half. Soloman Howard is, frankly, too young and handsome to be visually convincing as the Marquis and Padre Guardiano, but he can’t help that, I suppose. He ‘compensated’ with an imposing, mature bass and a remote, towering charisma that made something as simple as seeing him lurk around the edges of a scene feel terrifying to behold. Judit Kutasi, as Preziosilla—here reclassified as a “mysterious entertainer” with bunny-mask-wearing backup dancers rather than Romani— had a tightly controlled, locked down sound, with plenty of hidden depths and warmth. Also great: beloved (by me, certainly) character bass-baritone Patrick Carfizzi as Melitone. He was mean, funny, and helped to underline Verdi’s points again: there are petty, corrupt, and cruel men everywhere and in every profession, as surely as the world turns.

By the time the curtain fell, I was caught up in the centripetal force of Trelinski’s production. It’s far from perfect, but this one had enough movement to suggest an escape, if not from patriarchy, then from the boredom of a risk-free, drab retelling.

Photos: Karen Almond/Met Opera