No, this is not Aimee Semple McPherson, the evangelist, (think Anything Goes) but Mardones, Caruso, and Ponselle.

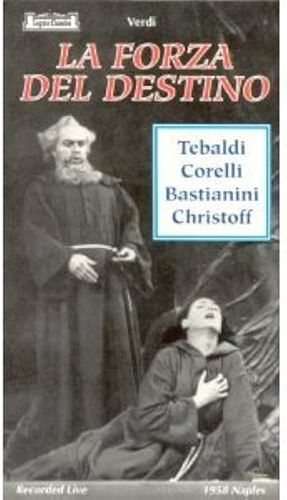

However, while there are several studio recordings available, none have been made since the 1990s and all of them leave something to be desired. Fortunately, there are a few legendary performances that have been preserved and in relatively good sound. Going straight to the top of the list, the most legendary is also a video. (3-15-58; San Carlo, Naples – Francesco Molinari-Pradelli; Renata Tebaldi, Oralia Dominguez, Franco Corelli, Ettore Bastianini, Renato Capecchi, Boris Christoff) When this 1958 San Carlo, Naples was released commercially on VHS (later DVD), it garnered a full page review in The New York Times. A dream cast: Renata Tebaldi, Franco Corelli (his role debut), Ettore Bastianini, and Boris Christoff in magnificent form. Okay… one must ignore the poor video quality, not to mention the flapping drops, but, oh! the singing!

Having said that up front, I should backtrack to some historical recordings and performances, that is before that 1958 Forza. Without question, one of the most exciting and historic nights in the annals of the Metropolitan Opera must have been the première of La forza del destino on November 18, 1918. The stars – in heaven and on stage – were aligned: Enrico Caruso, Giuseppe De Luca, and José Mardones. However, most attention centered on the Leonora who was not only making her Metropolitan debut, but appearing in any opera for the first time anywhere. She turned out to be whom many consider as the greatest soprano ever to grace the stage of the Metropolitan Opera, the then 21-year-old Rosa Ponselle. It’s a shame of course that there is no complete recording with that opening night cast, but there are several recordings made by them of excerpts. Caruso recorded the tenor aria, but most interestingly, recorded the three tenor-baritone duets each with a different baritone: Antonio Scotti, Giuseppe De Luca, and Pasquale Amato. In 1928, Ponselle recorded a heavenly performance of the conclusion of Act II, the “Vergine degli Angeli,” with Ezio Pinza and the entire finale with Giovanni Martinelli and Pinza. She also recorded the “Pace” four times.

Forza maybe more than any other Verdi opera can stand or fall by its conductor. If you don’t believe that, listen to the 1956 Decca recording with possibly more stars (Tebaldi, Mario Del Monaco, Giulietta Simionato, Bastianini, Fernando Corena, Cesare Siepi) than any other and see how flat that can fall. On the other hand, some of those same stars (Tebaldi and Bastianini) even with the same (or in spite of the same) conductor can, under live circumstances, pull off a great and legendary performance that made it on to that historic video. The conductor issue applies especially to the first “complete” Forza to be made. (1941; Naxos; Turin Ch. & Orch. – Gino Marinuzzi; Maria Caniglia, Ebe Stignani, Galliano Masini, Carlo Tagliabue, Saturno Meletti, Tancredi Pasero) It was also one of the first complete recordings of any opera to be made in a studio. This 1941 recording, originally released by Cetra on 35 78-LPs was magnificently remastered by Naxos to two CDs in 2002. There are small snippets missing here and there but the “Sleale” duet is the only major cut. Still, this can be considered one of two “reference” recordings. The fact that it was made up of 4-minute sections in a studio now seamlessly combined to create a theatricality more vivid than many of its successors on disc is truly a miracle of modern technology. It is one of the very rare studio-made recordings that sounds like applause is missing at the end of most of the numbers. That this exciting performance evokes theatre, not studio, and a totally Italian instinct is due entirely to its conductor, Gino Marinuzzi. Well-known and a major figure in the operatic world, especially throughout Italy before the war, this was his only recording prior to his untimely death in 1945. The cast exudes Italianità at its best. Besides Maria Caniglia, the standout performance here is the Guardiano of Tancredi Pasero.

The other reference recording, truly a state-of-grace, is the legendary 1953 Florence performance. (6-14-53; Florence – Mitropoulos; Renata Tebaldi, Fedora Barbieri, Mario Del Monaco, Aldo Protti, Renato Capecchi, Cesare Siepi) On the podium was the illustrious Greek conductor, Dmitri Mitropoulos. Mitropoulos transformed the opera into an outstanding dramatic work in spite of the usual “Sleale” cut and smaller ones here and there. Most critics deem him to lead the finest conducted performance of the work, or at least on a par with Marinuzzi’s and with an all-Italian cast just as authentic. Those who are familiar only with Tebaldi’s many studio recordings will be amazed at the depth of feeling she brings to every note she sings.

This was one of those evenings when Tebaldi was unequalled in the role as well as in voice. On listening to the second act finale, one can understand why Toscanini said hers was “the voice of an angel.” In this fabled evening she is equaled by Del Monaco, Barbieri, Capecchi, and Siepi. Mario Del Monaco was always at his best when Mitropoulos was the conductor, not only here, but in another remarkable performance, Ernani. He was always subtler and more musical on stage than in the studio, more stylish than usual. Here he is in magnificent voice in what was possibly his best role other than Otello. This doesn’t mean one actually had to like his sound and many didn’t, myself among them. Still, there is no question about his being exciting. For most, this is the definitive performance of La forza del destino and should be for anyone at least if it weren’t for the cuts and somewhat poor sound of the recording itself. Along with the Marinuzzi recording, these are the “reference” recordings. Nobody sings Italian opera like Italians!

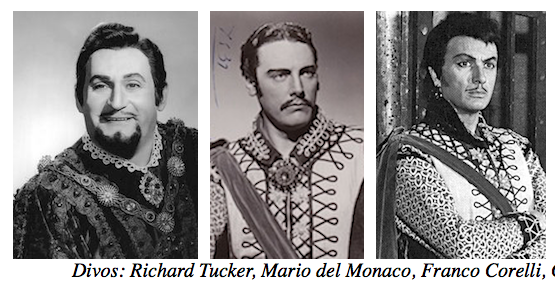

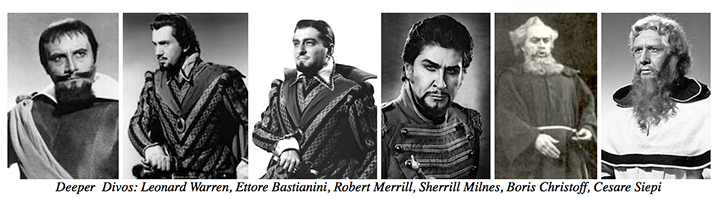

The first studio recording of the modern era, albeit not in stereo, is the “Callas Forza” – there’s not a lot of reason to consider it anything other than. This 1954 EMI recording gives us Maria Callas in a role not generally associated with her. In a role that calls for voice, and more voice, Callas is surprisingly good and gives the role a depth of character that would be beyond the comprehension of the role’s usual exponents. Those would include the three Verdi singers who dominated the role of Leonora after Ponselle and up to the present time, specifically, the era of the ‘50s through the mid ‘70s: Zinka Milanov, Tebaldi, and Leontyne Price. They had their equally magnificent male companions: Milanov was pretty faithful to Richard Tucker, but Tebaldi had multiple lovers – two-timing Dick, Mario, Franco, and Giuseppe di Stefano– while Leontyne ran off also with Franco and Dick too (he got around a lot) as well as Carlo Bergonzi and Placido. And they were harassed by the likes of Leonard Warren, Ettore, Robert Merrill, and Sherrill Milnes and calmed down by Boris, Jerome Hines, and Cesare. The latter, Cesare Siepi, sang the role with all three divas, just as he was fortunate enough to sing Oroveso to the Normas of Milanov, Callas, and Sutherland. It was another era, a Golden Age, and I’m glad I’m old enough to have seen them all!

It would seem like the Met presented more performances of Forza than any other company, though with all the cuts it often seemed like The Met vs. Verdi. Regardless, all those singers with the exception of di Stefano and Christoff sang the opera there. One could say all their performances were legendary, but based on Milanov, Tebaldi, and Price, I will whittle it down to the ones I think were the best:

- 3-17-56; MET – Stiedry; Milanov, Elias, Tucker, Warren, Corena, Siepi, Sgarro, Votipka, De Paolis, Cehanovsky – arguably, Milanov, Tucker, and Warren sang better in the 1952 broadcast, but the later performance is better overall

- 6-14-53; Florence – Mitropoulos; Tebaldi, Barbieri, Del Monaco, Protti, Capecchi, Siepi – the #1 choice!

- 3-15-58; San Carlo, Naples – Molinari-Pradelli; Tebaldi, Dominguez, Corelli, Bastianini, Capecchi, Christoff – also video

- 3-12-60; MET – Schippers; Tebaldi, Dunn, Tucker, Sereni, Baccaloni, Hines – this performance was one week following the death of Leonard Warren who was replaced by Mario Sereni

- 3-9-68; MET – Molinari-Pradelli; Price, Pearl, Corelli, Merrill, Corena, Hines – Price and Corelli made their Met debuts on the same evening in 1961 in Trovatore.

- 3-22-72; MET – Veltri; Price, Casei, Bergonzi, Paskalis, Corena, Siepi

- 1976; RCA (Studio recording) – Levine; Price, Cossotto, Domingo, Milnes, Bacquier, Giaiotti

- 2-25-77; MET – Levine; Price, Elias, Domingo, Milnes, Capecchi, Talvela – in-house recording; this performance precedes the broadcast that was with Cornell MacNeil

It is either of the last two performances that would be my recommendation if one is limiting oneself to just one recording. These are both complete … no cuts! Almost the same cast, the RCA studio obviously offers better sound but there is nothing like the frisson of a live performance that the studio cannot offer. The sound is remarkably good for the “pirated” 1977 performance for which the tape recorder must have been on someone’s lap and the recording has whatever it is that is lacking from the broadcast a few weeks later. Granted, Leontyne is never as good as in the earlier performances, just as Renata was in her earlier performances but she is still sensational. But it is Domingo, in particular, who seems to be giving the performance of his career. The same could be said for Milnes. As for studio recordings, again Price is better in her earlier recording (1964; RCA – Schippers; Price, Shirly Verrett, Tucker, Merrill, Giorgio Tozzi, Ezio Flagello) but the totality of the latter makes it preferable. Price also had a telecast in 1984, but that was sort of past the sell-by date and the rest of the cast is unappealing. Both Milanov and Tebaldi had major studio recordings, but Zinka’s 1959 RCA was way past her sell by date as it was for her tenor, di Stefano. As explained above, despite the greatest cast possible, Tebaldi’s 1955 Decca performance doesn’t work.

Eileen Farrell and Gabriella Tucci

Three other divas of this same time-period deserve to be mentioned and definitely heard: Eileen Farrell, Gabriella Tucci, and Montserrat Caballé. Farrell should have been the greatest Wagnerian singer of all time. Instead, she only performed highlights in concerts and on legendary recordings. On her nationally broadcast radio show during the ‘40s, she became a household name. She sang just about everything written for the soprano voice in defiance of any fach. Whatever version of the story you might have heard about the five seasons she was at the Met, it seems to boil down to Bing didn’t like her and she didn’t like Bing. The voice was that of a true dramatic soprano with a warmth that even Tebaldi might envy. Although by any stretch of the imagination, she was not an actress, but she was also much more dramatically alert with words than any of the other three divas. In her broadcast Forza, (12-30-61; MET – George Schick; Farrell, Helen Vanni, Tucker, Merrill, Corena, Hines) one knows this immediately from the urgency of the first “angoscia.” As for Messrs. Tucker, Merrill, Corena, and Hines, they were all in typical and brilliant form. The “Solenne in quest’ora” duet is especially memorable. If Merrill mixes up some of his Italian articles, he is also singing the role for the first of many times; he also left out a lot of notes in the aria. Special mention should be made of Alessio de Paolis who had been singing Trabuco since the early ‘40s and whose last run this would be. He was one of the Met’s treasured comprimarios through so many decades. I remember most fondly his Old Prisoner in La Périchole.

The other Leonora besides Farrell to appear between Tebaldi and Price was Gabriella Tucci (2-6-65; MET – Nello Santi; Tucci, Grillo, Corelli, Bastianini, Tozzi, Elfego Esparza). For truly stupid reasons, I always resented Tucci because she seemed to be the perennial replacement for roles that Tebaldi was supposed to do at the Met: the original Alice Ford in the legendary 1964 Zeffirelli Falstaff; also, in 1963 after Tebaldi had to drop out of her Adrianas to recover her voice, Tucci stepped in to replace her in a new production of Otello that was to follow. Tucci’s voice was slight compared to Tebaldi’s or Milanov’s or Farrell’s or Price’s, nor was it a particularly distinct sound, but it was beautiful and stylish and she was quite successful as Aida and most of the spinto-Italian repertoire that came her way. What an exciting performance this Forza is! Admittedly, the excitement was really all about Franco and Ettore (Believe me, I know – I was at the prima of the run!). The highlight of the performance was when Ettore slapped Franco across the face during their final duet. The whole audience gasped in unison, but out they came covered with smiles for a curtain call.

For whatever reason, Franco Corelli found the Verdi “Iberian” roles (Ernani, Trovatore, Forza, Don Carlo) particularly congenial for him; perhaps not so much for Verdi, but certainly for Corelli. No question that Corelli was abusing his superstar status, but the audience was enthralled. Despite have the most exciting voice and presence ever of any tenor (it was not really a beautiful sound) yet at times, like in the concluding solo phrases following the “Sleale” duet, Corelli could pour out molten lava sound. It was precisely the right instrument to convey all of Alvaro’s sufferings. At this performance, Ettore Bastianini was returning to the Met after an absence of four years and was reported not to be in good health. Perhaps his singing wasn’t quite the same as it had been in the 1958 San Carlo performance, but he remained the most exciting Carlo of all. His macho approach and gorgeous voice with a built-in snarl was perfect for Carlo and Bastianini’s high F-flat on the duly extended “finalmente” at the end of the third duet was filled with all kinds of nuances. Tragically, he died of cancer about two years later. The conductor, Nello Santi, was good to have around as an Italianate routinier; the overture was particularly exciting, but on this evening up against the forza of Signori Corelli e Bastianini, he was able to contribute as little as possible to the performance short of actually staying home. This was a performance that has stayed long in my memory and hearing the broadcast via Sirius only renewed the memories.

Even though the Met was never fortunate enough to have her as the Forza Leonora, Montserrat Caballé sang the role quite often and she certainly can join the list of the greatest Leonoras. The mid-70s also found Caballé at her strongest (in the sense of dramatic soprano) vocally and she was ideal in most of the late Verdi roles (early and middle too). She has been called by none other than La Tebaldi “the last prima donna”; she was certainly the last of the great Verdi sopranos. The role of Leonora enabled Caballé to reveal the full range of her voice and her entire arsenal of tricks: glorious tone, long-breathed phrases, diminuendos, high, floated pianissimi, imposing chest voice. Few sopranos could fill the familiar arias with such lovely, little nuances or float so ravishing a pianissimo at the “invan la pace.” Of the major singers to sing this aria, she is the only one to sing the final “maledizione” come scritto, that is without adding an extra maledizione that has become tradition. I used to prefer the traditional version, but when done as well as it is here (6-18-78; La Scala – Giuseppe Patané; Caballé, Maria Luisa Nave, Carreras, Piero Cappuccilli, Sesto Bruscantini, Nicolai Ghiaurov) and especially the performance at Caramoor with Takesha Meshé Kizart, I have come to like what Verdi intended more. Poor José, all those magnificent performances he sang with Montse – she always looked like she was robbing the cradle. Here he is distractingly handsome and looking like a 16-year-old, though he was actually 31. Both he and Caballé were singing their roles for the first time.

Like Caballé, José Carreras is in stupendous form. Granted, this lyric tenor should never have been singing this dramatic role; but here he is in splendid form, a beautiful, polished sound with easy top notes, a pure legato, and impeccable phrasing all with glorious results. In fact, all three principals show more far more commitment than usual though none of them are exactly inspired actors. Nicolai Ghiaurov sings like the Almighty Himself. Sesto Bruscantini sings well but lacks any humor. Maria Luisa Nave’s slutty Preziosilla, unattractively sung, leaves no doubt that she was more than just a “camp follower.” Giuseppe Patané does not follow the usual Italian conductor tradition of brisk tempos; many are truly lethargic, however, he was a late replacement for an indisposed Zubin Mehta. The chorus and orchestra are La Scala’s – nothing more need to be said. This is a video performance; the sets are based on Goya paintings and at times could be taking place inside the Prado. Even the costumes seem to be painted. There is no attempt at realism. One of the monks must have been a hairdresser … even after she had been living in a cave for some five years, Montse is still perfectly coiffed. And for the final trio, she dies standing up, still wearing her high heels! Regardless, this video is only one degree away from being the equal of the legendary Naples 1958 video.

1978 pretty well ends the history of great performances of La Forza del Destino. Yes, there were a few studio recordings that I won’t even mention. Was it The Curse? Was it the dearth of Verdi singers? I would go with the latter. Meanwhile, though, two recordings of the original 1862 St. Petersburg version came out; one, a concert from Opera Rara and the other a Kirov Opera performance released by Phillips both as a video of a live performance and then a studio recording. (1995; Philips/Kirov – Gergiev; Gorchakova, Borodina/Tarasova, Grigorian, Putilin, Zastavny, Kit/Alexashkin; Original St. Petersburg) It’s appropriate that the first recording of the original version of Forza should emanate from St. Petersburg where the opera had its première in 1862. While that première had a mostly all-Italian cast, this current production is entirely Russian, and sounds it. I don’t know which came first, the studio recording or the live performances.

The cast is virtually the same except for the Preziosillas and Guardianos; the studio ones are listed first. Olga Borodina is a superb Preziosilla. By force of destiny, the Alvaro, Gegam Grigorian, died the day before I watched the video. Grigorian did not exactly cut the most romantic figure and he sang Alvaro like a crude Corelli (I know that seems redundant). In the live performance, not surprisingly he barely makes it through the aria that ends that third act aria, and one almost has to assume that if he can’t make it, no one else is going to either. Both Grigoriam and Galina Gorchakova have huge, dramatic voices perfect for Alvaro and Leonora except that both are totally devoid of Italianità. The live performance had sets that were recreated from the original designs for the 1862 première; from an historical perspective that is another major reason to see this. Unfortunately, it seems like the staging was also recreated as NO ONE can act. Otherwise, one can make up one’s own mind as to what worked and what didn’t in the original and why. I wish someone would make a recording of the French version.

It’s nice to know that I could still be thrilled by a performance and especially by yet another “Pace, pace, mio Dio.” I was confirming a fact on Wikipedia, and it said something about the 2008 Caramoor performance (7-26-08, Caramoor – Crutchfield; Kizart, di Villarosa, Ninua, Borowski, Mistico, Chávez) giving a concert performance of the critical edition of the 1862 version plus never-performed vocal pieces from the 1861 version. I thought that last date was a typo, but no, that refers to what Verdi wrote originally before any rehearsals and the subsequent cancellation of the original date in 1861 for the première. I was at this performance (no, not the 1861, but at Caramoor) and I remember being thrilled by the then 26-year-old Takesha Meshé Kizart and assuming she had a tremendous career ahead of her. I have no idea what happened to her. This to me was the best spinto voice to come along since Price. But it is not only her; the Melitone of Marco Nisticò is a real standout and the entire performance is hugely exciting even if the sum is greater than some of the parts. I’m sure this is entirely due to Maestro Will Crutchfield’s energy and commitment. In fact, the whole performance shows a tremendous commitment from all involved: the soloists, the chorus, the orchestra. This very much replaces the Kirov “original” version recording on every level (perhaps not sound, but it’s not bad). This is one very exciting performance and a wonderful way of ending this sojourn. Those interested in hearing this performance are encouraged to check out parterre‘s podcast, Chris’s Cache, later this week.

From 1978 to 2019 … 41 years it took to assemble a cast and conductor worthy to stand beside those performances of the ‘50s-‘70s. And it was televised in a production that was somewhat realistic and acceptable despite some quirks here and there. (4-2-19 ROH; Pappano; Netrebko, Veronica Simeoni, Kaufmann, Tézier, Alessandro Corbelli, Ferruccio Furlanetto) Anna Netrebko continues to grow and improve. Her performances of the other Leonora and Lady Macbeth can compare favorably with the greats. Add her Forza Leonora. So do the performances of Jonas Kaufmann and Ludovic Tézier. The three together stand just a notch below those of Milanov-Tucker-Warren, Tebaldi-Corelli-Bastianini, or Price-Domingo-Milnes. Things are looking up!

When I originally wrote this ten years ago, a new production had been announced for the following season (2017-18). Casting was ominous… Aleksandrs Antonenko, Sondra Radvanovsky, Dmitri Hvorostovsky, Nicola Alaimo and Ferruccio Furlanetto. Maestro Levine was the first to back out to be replaced by Dan Ettinger. Then everyone else did and the Calixto Bieto production was mercifully cancelled. The “curse” lives on. Now, in a few weeks, another new production is slated to open. Typically, I already have opinions. But I’ll save them …for now.

CONCLUSION

And by “conclusion,” not only do I mean The End (finally!!!) but the conclusions, as in opinions, to which I have come. Nothing I have said changes my mind from what I originally said, listening to Forza is better than seeing it – but there is hope! Producers trying to improve the opera’s reception, frequently produce their own version. As I approach these essays of mine as if I were about to design or direct my own production, I would be no different. As I study the libretto, there is extremely little in it that actually refers to the third act taking place in another country (Italy). There is even less reason for it to do so, other than perhaps history. If I were staging it, I think I would keep the entire opera except for the opening interior scene of the Marchese’s villa and the final scene of the cave all within a town square in Seville; the inn on one side, the monastery on the other. I would probably bring in certain set pieces to denote the passage of time: tents, devastation of war, signs of increasing poverty, and so forth. With the luxury of a turntable, for variety those places could revolve to their respective interiors. Which war is being fought is entirely irrelevant to the plot. Now it makes sense for all the characters to keep showing up. Perhaps run Acts 2 & 3 together instead of 1 & 2. Just some thoughts – sorry for the digression.

To learn more about the opera, take a look at the previous installments in my Forza series which cover Verdi’s influences, the opera’s various versions, and its characters.