His 2023 Banishing Orientalism takes a more theoretical tack, contending, “Orientalism was actually foundational to the development of ballet as we know it today, rather than being a side note—mere artistic device—as it’s often treated by art historians.”

Now, for the first time, he is turning his attention towards opera—his production of Madama Butterfly, which shifts the action from Nagasaki to 1940’s San Francisco (including small tweaks to the libretto; the score is left intact) opens on September 14 at Boston Lyric Opera.

Before rehearsals started, Phil sat down with the box to chat about his production, opera’s cultural appropriation problem, and why the last thing he’s trying to do is cancel Puccini.

Harry Rose: I know a little bit about your relationship to ballet, but tell me about your relationship to opera.

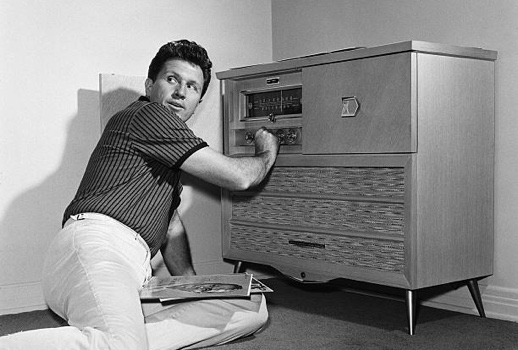

Phil Chan: I was actually a boy soprano and did a production of Magic Flute when I was in middle school, but I don’t think I really got it until it was my freshman year of college when I went to see Baz Luhrmann’s La bohème on Broadway. I sobbed through the entire thing — It was just beautiful.

And then, I had a board member early in my career who and had front row tickets to the met every night, and she just loved going to the opera and nights that she didn’t have to entertain, she would just call me at the last minute and say, “Phil. Put on a suit. Meet me at the Met at 7 o’clock. We’re seeing Gotterdämerung, we’re seeing Carmen, we’re seeing whatever.” I saw everything at the Met a couple of years, like from the front row which is a crazy education. I also did the Dance of the Hours in Gioconda and produced some opera programs for singers and students.

But this is my first time directing, which is really exciting. I’m also staging a full-length bayadère right now, so I’ve literally got these like two giant warhorses right now, the biggest Oriental spectacles in both opera and ballet. But really, it’s the same process: how do we shift these works from being strictly Eurocentric (by Europeans, for Europeans) to a contemporary, diverse American society today — which includes white Americans who are not are not Europeans.

We are not doing white Americans any favors by pretending that we are European because we’re not, right? This work includes all of us who are alive in America today. So, how do we make this work bigger for everybody. Opera and ballet really are twin art forms separated at birth, so there is a lot in terms of how the sausage is made that is similar, but also so much that is like radically different, which is just wild to me, but also a lot of fun.

As a dancer, I can never really let go and like enjoy a dance performance without focusing on so many small details. But with opera, not being a singer, I don’t know how the physical mechanism works, so there is a mystery that is still there that like can still give me an emotional reaction. And I think being able to have that a little bit of that distance has been helpful and fun just because I still get moved by Puccini in a total sucker sort of way. And I get how it works from a structural perspective, so how do we play with that for audiences today?

Harry: So, what is your taste in opera like? What do you like to listen to?

Phil: To be quite honest, I love humor. We forget that opera is not just like tragedies like Norma. Oh, my God! Like, kill myself! I just… – let’s have some fun! Let’s laugh! Let’s entertain! Let’s tell dirty jokes! There used to be all of that and opera and we still like that. How do we recreate that kind of appreciation for opera that isn’t just as this really serious thing that you pay lots of money and wear a tuxedo and go to, but also the thing that you listen to in the bar and is stupid and funny and true and urgent and feels like it’s about you and that you’re in on the joke.

We look at the financial futures of this art form and a lot of these mid-size opera companies are not going to survive the next five years. So, how does opera as an art form integrate itself into American society alongside Netflix, Zoom, etc? No one’s going kill opera, but we need to help it change to keep staying relevant. What I’m going is just like what opera makers using VR and doing site-specific work are doing — this is just another way to make it relevant.

Harry: What surprised you coming into the world of opera from ballet?

Phil: Everybody sees something that they would like to change, but the, in the same breath, are opposed to changing anything. You look at like Peter Sellars, Ai Weiwei, Baz Lurhmann, people from other disciplines who are not opera people—innovation always comes from outside of the center.

What I’m offering is just a new way of looking a work on the chopping block. A lot of folks are too scared to do it. If you want to talk about cancel culture, the definition of cancel culture is saying, “we’re not gonna do this opera because it’s too racist or sexist, or whatever is to be presented.” My angle is to say, “Okay, well, let’s take this opera for what it is: As a work itself, it contains some of the most beautiful music in opera. It speaks to the human conditions.

It’s got really good redeeming values as a work of art. It’s also major part of the opera ecosystem. You do a Butterfly, you sell that out, and you can use that money to commission a Black composer to do a new opera. You need the Butterfly in the ecosystem for now to be a part of the larger opera network. If you want equity, you can’t just say, ‘cancel Butterfly, and instead let’s do all new Asian composers exclusively.’ I’d love that, but you’ve got to do it in steps. You can’t just cancel Butterfly, but you can do it better.

Even just with having a work hinge on the tragedy of an Asian woman—then, you leave the theater and another Asian woman is pushed onto the subway tracks, or followed home and killed in the streets, or because of Covid, an old Chinese lady’s gets the shit beaten out of her. That’s the reality we live in, and that’s not Puccini’s fault, but times have changed.

If you think about what was contemporary for Puccini, it was Commodore Perry and the opening of Japan. That was the defining thing for Japan then. What’s the defining thing for Japan now? Pearl Harbor, World War II—those are the big moments in our collective consciousness.

Commodore Perry doesn’t mean anything to us anymore. The Meiji Restoration doesn’t mean anything to living people today. It’s too far away for us to mean anything real, whereas there were people who were incarcerated and lived during WWII who are still alive.

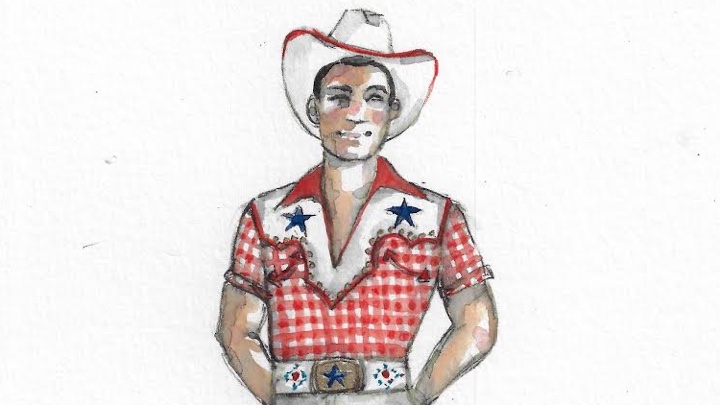

I start by asking, “what else could it be?” She’s a 15-year-old geisha, but what’s a geisha today? What’s a congruent setting for a geisha? What else could it be? A jazz singer! ‘Geisha’ means ‘artist,’ so what if she’s an American jazz singer that just happens to be of Japanese heritage? What would that look like? How do you make that story about us? How do you center an Asian American story (because, after all, Butterfly is one of the first Japanese Americans, in a sense, in literature) instead of an outsider’s fantasy?

So, we brought together a team of, save for choreographer Michael Sakamoto and myself, a Asian American women to reframe this. I really have to give credit to Nina Yoshida Nelsen, who is the dramaturg and an artistic advisor for BLO and has done over 200 productions of Suzuki. Butterfly is for her like Nutcracker is for me. She knows the score cold and also her family was incarcerated, so this is really personal to her. But our question was, how do we keep Puccini intact? The score is not changing at all. All the notes are there.

Harry: What language are we singing in? What kinds of changes did you make to the libretto?

Phil: Little things; ‘I’m the luckiest girl in Nagasaki’ has become, ‘I’m a luckiest girl in San Francisco.’ Just little things like that. There are moments where a different character might sing a line. In the original, Pinkerton and Sharlpess have that whole exchange about how old she is so they can say, “Let’s get married so I can fuck you already.” That’s in the first 10 minutes of the opera, and in Puccini’s time, people have said, “Oh, yeah, that is just the way it is.”

Now, audiences say, “that’s gross, he thought she was 10?” Our reaction is not an ‘ew’ that tells you a lot about Pinkerton, it’s an ‘ew’ that takes you out of the story and makes it seem like this is a fairytale. In our production, which is set in a nightclub in San Francisco, Sharpless delivers the line about “the age for games and candies” to Pinkerton to make a point about how he’s going to war instead. It’s not changing that line, but we make it mean something different. But this type of updating is not radical or new; the words have the staying power, and I think we need to let Puccini be a little bigger than what it was. Last year, BLO did La bohème backwards — I’m at least playing all the music in the right order!

Harry: About that ‘ew’—in your books, you point out that a certain amount of discomfort isn’t a bad thing when dealing with material we might find offensive. How did you figure out where that boundary was between an ‘ew’ that solicits a productive discomfort verses an ‘ew’ that was alienating?

You need to make these characters feel alive to feel relatable. You may not relate to one specific character, but you might relate to an emotion present in lots of these characters. And that’s why we like opera, for those very human, often very flawed sides of being. If somebody is so alien and literally wants to fuck a 10-year-old, it’s really hard to identify or humanize. It makes you closed off as an audience member, which would not have had that impact in Puccini’s time because they had different ideas about the age of consent. And those cultural differences between Italy and Japan have changed.

There are not 15-year-olds getting married in Japan today. So, why are we perpetuating this story about these hypersexual, hypersubmissive young Japanese girls? It presents a barrier to seeing a more human side to these characters. I’ve done all this work in service of that while maintaining a very conservative impulse to make only very minor changes to what Puccini made.

Harry: I’ve heard you talk a lot about wanting to keep ‘Puccini’ intact, but what do you think of the other side of the music, the libretto? What makes a good libretto and do you think what Illica and Giacosa did for Butterfly is a good libretto?

Phil: I think a good libretto is well structured, has a good arc, has a wave that the audience can ride, with a story that music gives another dimension to. This story is complicated because it’s dealing with real issues: cross-culturalism, belonging, racism, religion. This is an opera about a biracial baby! We have to remember just how radical this opera was. It was something that contemporary and messy and Pinkerton is probably the most hated tenor. It’s barely even a love story, if you think about it; it’s a story of betrayal disguised through beautiful, soaring, romantic music and that tension is interesting and exciting and provocative.

And all those themes like racism and belonging take on a fresh meaning in our current moment in society, so we’re leaning into the conversation in this way: how can we save Butterfly and American history? People are trying to ban books about Japanese incarceration in Wisconsin, but this is our American history. I’m not Japanese, I’m Chinese, but I’m American, and this is a part of my American history. I think it’s important for us to remember, and it feels a lot more urgent and relevant than the Meiji restoration.

Harry: In terms of those urgent, exciting, and provocative themes Butterfly deals with, do you think the opera comes to any conclusions about any of those things on its own? Will your reimagining engage with any of those conclusions?

Phil: I think that’s a question for you after you see it. I’m reflecting on how many productions center around the tragedies of the action (or inaction) of the characters. In this production, there’s also just some tragedy that is by circumstance. But not every death has to end in a loss of life — what are other losses that aren’t literal death, but are so deep you have to carry them for the rest of your life? Is giving up on your dream a form of suicide?

Harry: That’s really interesting.

Phil: Oh, and I’m gonna gut you like a fish — you’re gonna be blubbering so hard at the end. It’s gonna be a waterproof mascara occasion.

Harry: In Final Bow for Yellowface, you concluded that because of Puccini’s earnest research and incorporation of original Japanese music, that Madama Butterfly could not be unilaterally considered a work of cultural appropriation. Has your thinking on that changed at all since 2021?

Phil: What has emerged for me is the difference staging makes. This is the same score that you would hear in countless other opera houses around the country and some versions are really, really racist. Mine will not feel that way, and it’s the same music. So that tells us is it’s not necessarily the music. The problem is the lack of imagination in staging. Letting an outsider, a choreographer, a person of color take a swing at it comes with a lot of power and responsibility.

Harry: It sounds like, for you, the music is a neutral quantity.

Phil: I wouldn’t say ‘neutral,’ but I would say ‘constant.’ Those are the rules of the game, right? I want to do Madama Butterfly, not a variation on Madama Butterfly, not M. Butterfly, not what my dad calls My Dumb Butterfly. I’m doing the opera. It’s cultural appropriation if you stage it in a racially insensitive way. But you can also stage it in a racially sensitive way. I’m interested in finding that possibility as an artist.

Harry: So, for someone walking into the theater without having known about all the intellectual and community work you’ve done, is there anything that might flag this as a of racially sensitive, intellectually informed production or, won’t that be visible?

Phil: I’m just gonna gut you like a fish. I’m gonna give you some good music and by the end, you’re gonna be sobbing like a baby. Like a biracial baby.

Harry: I want to ask a question about a word that appeared every so often in your book Banishing Orientalism: authenticity. With all the competing strands in opera, at least in the context of Madama Butterfly, how do you define authenticity and what or to whom are you trying to be authentic?

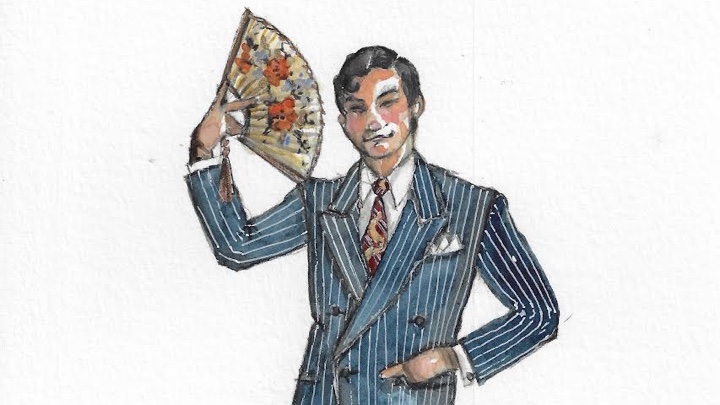

Phil: I look at authenticity, but also integrity. That’s the sort of balance I’m looking for. Take the swastika as an example. A swastika is an ‘authentic’ symbol, right? But is it being used with integrity? No. So, in this case, what are we being authentic to? Well, let’s first look at the text, Pierre Loty’s semi-autobiographical, somewhat fantasized and exaggerated version of his own naval pursuits with Japanese ladies which then turned into an American play by David Belasco, which then turned into Puccini’s opera. So it’s those 3 stories we’re filtering through the lens of an Italian composer who’s looking at both contemporary America at that time, at the turn of the twentieth century, and pretty contemporary Japan.

That is what we are being authentic to, not to Japanese culture or American culture. Who cares if we’re being authentic to Japanese people or not? It’s not about Japanese people and was never meant for Japanese people. It has nothing to do with Japanese people except that they are characters in the story. That’s the only reason. When people say, ‘let’s bring in an authentic Japanese fan dancer, and teach people how to wrap a kimono in authentic way’ but still do a show that doesn’t have integrity, it doesn’t really work. If we can’t do it with authenticity — and that’s not even possible — then how do we do this with integrity?

By re-centering around an Asian American story while keeping the music intact in order to still give you the same emotional impact as Puccini had intended for you to have. If I can make you cry at the end and make you feel something like Puccini what wanted you to in the music, then I have succeeded by Puccini. And if I can tell it with integrity that isn’t at the expense of a 15-year-old hypersexual, hypersubmissive Geisha prostitute, that’s how I do it with integrity

Harry: I know we’re we’re almost at time — do you have any other plans for work with opera in the future?

Phil: Bayadère comes next, at the end of march, then a series of ballet festivals around the country that are all AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) choreography. I’m talking to a few opera companies about a next opera and, without giving it away, I’m looking at a comedy in which yellowface plays a role.

Harry: It’s so interesting to me that you’re drawn towards comedy rather than tragedy!

Phil: Comedy is so much better, so much harder than tragedy. But the closest distance between two people is a joke. And we need it so badly right now. It’s not all just Giselle, Swan Lake, Romeo and Juliet, Traviata, or Tosca—It’s entertaining, it’s funny. It has to be more than that.

Comments