Those quick to condemn McBurney must have been unaware that his Zauberflöte has been enchanting audiences since it premiered in Amsterdam in December 2012. Subsequent revivals at the Aix-en-Provence Festival and the English National Opera (where it will be revived once again next spring) have assured its status as one of the 21st century’s signature Mozart productions. It proved far more satisfying than the even more widely traveled, but irritatingly gimmicky and shallow Barrie Kosky version which arrived at New York’s Mostly Mozart Festival from Berlin’s Komische Oper in 2019.

Audiences familiar with previous gloriously colorful Met Zauberflötes designed by Marc Chagall and David Hockney may be initially put off by Michael Levine’s spare set, but what transpires on it was consistently eye- and ear-catching. From the left side of the Met stage, Blake Habermann projected witty words or drawings that darted about in real time, while from her station on the right, busy Foley artist Ruth Sullivan conjured an captivating sound world designed by Gareth Fry. My fears that her vivid work might interfere with Mozart’s music were mostly unfounded, though I wasn’t happy that driving rainfall covered the beautiful ending of “Bei Männern.

Those attending this new Zauberflöte will be greeted by a nearly bare stage flanked by Habermann and Sullivan’s work stations and a raised orchestra fronted by a passerelle rather like the one used in the Met’s familiar Il Barbiere di Siviglia. However, you should promptly be seated as conductor Nathalie Stutzmann will begin the overture before the chandeliers have started to ascend.

Zauberflöte was one of the first operas I fell in love with when I caught the opera-bug in grade school. Only years later did I learn how “problematic” it was for many; the uneasy mix of high and low, serious and comic; its misogyny and racial insensitivity; its mysterious Masonic roots, etc. While numerous modern productions have taken pains to address or correct these contentious issues, McBurney enthusiastically dives in embracing all of the work’s crazy extremes.

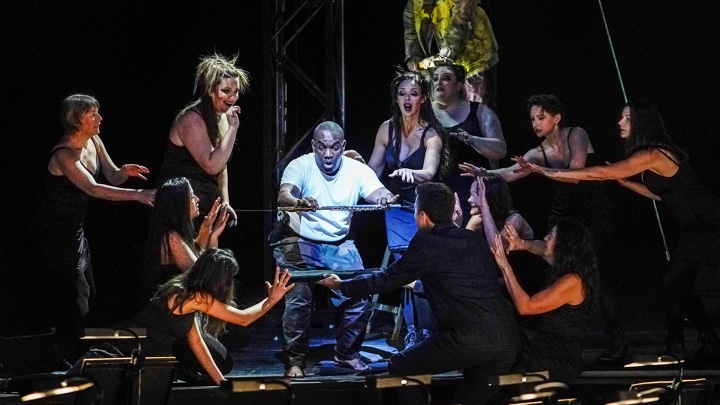

He populates his bustling updated Zauberflöte world with Schikaneder’s characters as we may have never seen them before. Sarastro initially gives off chilly corporate CEO vibes while the Queen of the Night is a terrifying crone pushed around in a wheelchair. Her horny three ladies, initially clad in combat fatigues, zestfully fondle the supine Tamino while business-suited Monostatos behaves like a sleazy perv. The three bent and wizened boy genii gesture with their canes to prevent both Pamina’s and Papageno’s suicides.

While I’m ordinarily in favor of “less is more” and was initially leery of McBurney’s busyness, I almost immediately fell under the spell of his “sensory overload”! In fact, so much was happening on stage that I must go back to catch what I may have missed before the run ends on June 10. I’ve enjoyed stage productions by August Everding, John Cox, Harry Kupfer and Julie Taymor, but I’ve never laughed so much nor been so moved by a Zauberflöte until McBurney’s where even its Busby Berkeley-flavored finale brought tears to my eyes.

Following her sublime Met debut two weeks ago leading Don Giovanni, Stutzmann once again led a fleet and transparent reading full of ravishing detail. She accompanied her hard-working cast with considerable care so that the exposed orchestra never covered them. Keeping everyone together when singers were entering and exiting through the auditorium must have been challenging, but the entire operation came off beautifully.

Though through the years I have heard more ideal realizations of the opera’s leading roles, Stutzmann’s cast collaborated with a rare and endearing unanimity. Returning to his role after many years, Lawrence Brownlee embodied an immensely sympathetic Tamino, singing with energy and appealing tenderness. Sometimes his high tenor turned gravelly in the lowest music but it was all in all a gratifying departure from his 19thcentury bel canto outings.

Radiant Erin Morley too sometimes found Pamina a bit low, but her bold and forthright heroine floated heavenly high notes throughout. Her achingly heartfelt “Ach ich fühl’s” began with an unusually quick tempo gradually slowing as she sank deeper into despair.

Together the soprano and tenor bravely faced McBurney’s arresting water and fire trials singing while flying!

The lone veteran of the production’s 2012 premiere, Thomas Oliemans made his Met debut as an irresistibly rumpled Papageno. Armed throughout with his sturdy step-ladder (for catching birds, of course), he garnered most of the laughs while singing with a more than serviceable baritone. A delightful McBurney touch is having musicians Seth Morris and Bryan Wagorn play the crucial flute and glockenspiel solos rather than have Brownlee and Oliemans mime them. However, the ever-game baritone takes over from Wagorn in a particularly hilarious bit.

Kathryn Lewek has been the Met’s go-to Queen of the Night for nearly a decade and in her wrenching first aria demonstrated why. Never have I heard such pathos wrung from the mother’s longing for her lost daughter.

However, her usually fearless repeated high Fs in the “Die Hölle Rache” this time came out more like squeaks suggesting she might soon want to hang up her dagger. Stephen Milling returned to the Met for the first time since 2006 as Sarastro. He and Harold Wilson as his sonorous Speaker towered over Morley’s petite Pamina. Both exuded a commanding benevolence with Milling sounding stronger in his role’s higher reaches than its subterranean lows.

Brenton Ryan’s ringing Monotatos was a welcome departure from the usual thin-voiced character tenor rendition, while the Three Ladies of Alexandra Shiner, Olivia Vote and Tamara Mumford strongly continued the Met’s long tradition of deluxe casting for these roles. Once upon a time the company also used women for the three Genii—its 1970 edition featured Gail Robinson, Judith Forst and Frederica von Stade—but in 2023 we once again got boys whose pitchy piping did Mozart no favors. But this has been an especially boy-soprano-rich (sic) Met season: The Hours, Fedora, Champion and now Zauberflöte!

The Met’s 2022-23 season will long be remembered for its sterling Mozart Triple Crown: last fall’s memorable Idomeneo, followed this spring by Ivo van Hove’s new intensely brutalist Don Giovanni and now McBurney’s marvelously entertaining Zauberflöte. The trio may help take away the sting of the next season: only a revival of Taymor’s fanciful, brutally cut Magic Flute.

Comments