Hosted by the charismatic James Monroe Iglehart (whose performance in “Magic to Do” started the evening off strong), the performance managed to straddle reunion, tribute, and retrospective concerts with relative ease.

The performances in the “reunion” category, which reunited performers with the roles they originated or famously interpreted, were the most uneven. Andrea McArdle, in an early highlight, performed the songs she originated, “Maybe” and “Tomorrow” from Annie, her grainy timbre undiminished and her approach not punchy, but knowingly optimistic. But Francis Ruffelle’s “On My Own” from Les Miz has grown parched and squally since its first airing in 1987.

Later, LaChanze sounded ageless in “Waiting for Life to Begin” from Once on this Island and Andrew Rannells, also returning to a Tony-winning role, was rousing despite a basically whiny and pinched-sounding tenor in “I Believe” from Book of Mormon that prompted a woman a few rows ahead of me to throw up her hands in jubilation.

The “retrospective” performances, focused on Pippin, Annie, and Les Miz were strong on their own even if the thesis – that the Kennedy Center was intrinsic to the geneses of all these works—did not gel.

Norm Lewis delivered a showstopping “Stars” from Les Miz, even if Iglehart’s highlighting of the Kennedy Center in its musical of origin’s development elicited some seemingly predicted raised eyebrows. And Gavin Creel’s excessively ornamented and riffed “Corner of the Sky” was the evening’s most obvious example of the changes in performance styles over the past half-century.

But throughout, even during a fawning speech by Kennedy Center President Deborah Rutter, the venue itself seemed to shrink from view as a curator or incubator of new musicals in the past two decades.

A video montage that recollected the 2002 Sondheim Festival, during which Christine Baranski, Brian Stokes Mitchell, and more lovingly questioned just how the Center (under the leadership of Michael Kaiser) had been so audacious as to present 15 weeks of full repertory productions of Sondheim musicals, only reinforced that the past two decades have been fallow artistic ones for new show development at the Kennedy Center.

Maybe some of this streamlines with Rutter’s community-centric objectives for the center (Ahrens and Flaherty’s Little Dancer was the last musical developed under the Center’s auspices in 2014, just months after Kaiser’s departure).

But the packed houses of this weekend demonstrate that the D.C. public is willing to pay for musical theatre, certainly more so than they are to pay for the opera or symphony. And the weekend-long Broadway Center Stage programs, not revived since the pandemic, are nice but can hardly be considered cultural landmarks.

It may be surprising that our National Cultural Center never rose to become one of the great nonprofit incubators of new work, but it’s downright strange that that objective has seemingly no place in an otherwise expansive mandate. Is Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus! (The Musical) really the only sort of contribution that Rutter aspires for the Center to make to the musical theatre canon in the 21sr century?

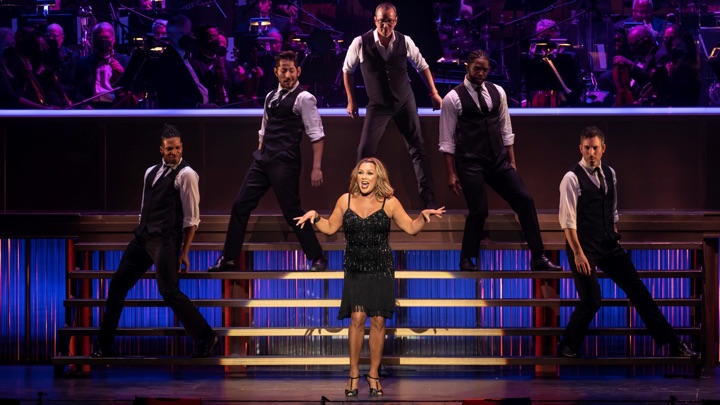

But I digress, because great talents. like Sierra Boggess, Tony Yazbeck, Stephanie J. Block, and more, still abounded. Boggess, an ingenue’s ingenue even at almost 40, was radiant, especially during my personal highlight of the evening, a complex and moving “Losing my Mind/Not a Day Goes By” duet with Vanessa Williams that balanced sincerity with style.

Yazbeck, whose old-school Broadway timbre, charming smile, and lightness on his feet was a force through “Buddy’s Blues” from Follies as well as the Gershwins’ “I Can’t Be Bothered Now.” He, along with Williams, Boggess, Block, and Iglehart, certainly seemed like the most individual artists of the evening. Their prominence throughout was welcome.

Indeed, there is something transfixing about Block, whose warm, pointed belt and nearly cringey earnestness” walk the line between naïve camp and honest-to-god earthiness, even if two-thirds of her numbers were not ideal fits (“Don’t Rain on My Parade” which was a tribute to Streisand’s mannerisms and a uniformly miscast “Move On” from Sunday in the Park with George opposite Rannells).

But in “Defying Gravity” from Wicked, a show she is known for, Block went to war with the song’s rangy tessitura—and the sparkly silver jumpsuit she wore for the number; her volcanic vocalism came out on top.

The evening had plenty of other strengths, not least the Opera House Orchestra which positively sang under Rob Berman’s direction (a particular asset considering how many of the pit orchestras of the represented shows have in reality been hacked to pieces).

And Marc Bruni’s limited staging carefully sidestepped any overdoses of pizzazz to satisfying effect. The evening was polished and sparkly (some might say it shined like the top of the Chrysler building.) But for those that yearn for an ambitious theatrical institution in the District, the evening felt a little hollow.

Next door at the Eisenhower, The Washington Ballet was wrapping up a performance of Julie Kent’s excellent staging of Swan Lake. I had taken it in the night before, mesmerized, and found myself continuing to think about it as I walked through the Grand Foyer and out the Hall of Nations.

In The Washington Ballet is the solid example of an institution with a long legacy whose focus on internal development and homegrown talent has begotten both artistic excellence and sold-out houses. The Kennedy Center might do well to watch and learn.