CAMERON KELSALL: I sometimes think of Sweet Bird of Youth as the fork in the road of Williams’ career—first appearing on Broadway in 1959, it closes out an undeniably successful decade for him, on stage and screen, and bisects his body of work, with his mature hits on one side and his experimental, often lambasted later plays on the other. It also finds him working in a more outwardly soapy milieu, as if he took Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and merged it with Peyton Place. I know what you mean, David, when you talk about the overripe elements of Brooks’ Cat movie, and I think those elements are here too—although to me, they’re much more baked into the material itself. Although there are some deliciously outsize characters in this play, I’ve always had trouble warming to it, generally preferring the seedier elements of Williams’ less polished work. Revisiting this movie for the first time in a few years, I found myself having the same reaction. On the cusp of moving into an uncategorizable era, Williams seems to want both a well-made story and a soap opera, and in the end, the audience gets neither.

DF: I think you’re being generous. At one point watching it, I was having so much trouble figuring out what was going on, I decided to try writing a bulleted list of plots and subplots. Here goes:

- Huey Long-style Southern White Man’s Castle politics

- Backdrop of the Korean war

- Chance’s loving and leaving Heavenly, and her subsequent hysterectomy and sterility for which his punishment is still sought by her politician father and his cronies

- Finley’s abusive treatment of his vivacious, loose-lipped mistress (a really sensational performance by Madeleine Sherwood, who should have been Oscar nominated)

- … and of course film actress Alexandra Del Lago’s rise and fall and… whatever, some of it alongside boytoy of the moment, Chance Wayne, who also aspires to a movie career

Whew. As Birdie Coonan would say, “Everything but the bloodhounds snapping at her rear end.” To be sure, all these themes are plausible Williams territory (especially the Alexandra / Chance scenes). They just don’t come together.

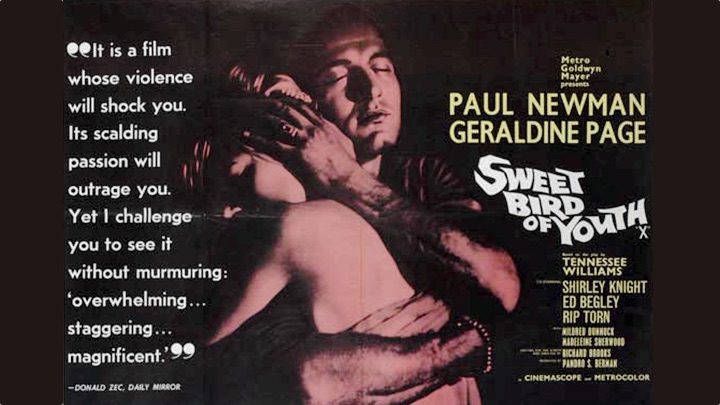

CK: Indeed—each bullet point here could be its own movie. There are some I’d rather take in than others, though. Although the young Shirley Knight lives up to her celestial moniker, I have to say I tired of her performance quickly; you’re exactly right that Sherwood’s juicy reprise of her Broadway role should have gotten the Oscar nomination. (And maybe some gay grad student should write a dissertation on how she perfectly embodies the Madonna/Whore divide in her roles here and in Cat.) And as great as Ed Begley is in his Oscar-winning role as Boss Finley, that entire subplot seems too much like Williams trying to channel Robert Penn Warren. No, really, wouldn’t any viewer—and least, any homosexual viewer—want to spend all their time in the languid hotel suite with Newman, at the absolute peak of his physical beauty, and Page, a truly glamorous trainwreck?

DF: I agree about Knight, but to be fair to her, I think Brooks does his least persuasive work on the Heavenly / Chance subplot. Admittedly, it’s nearly impossible to take seriously, but the original almost borders on Grand Guignol—seen here, sentimentalized and domesticated, it really fits into your Peyton Place construct. Paul Newman’s Adonis-like perfection is indeed worth the price of a ticket (and several rewatchings). But I actually don’t think he’s quite right for Chance—Newman is patrician, elegant. Chance is meant to be sexy-thuggish and pretty dumb. I kept wanting Rory Calhoun or someone like that. But actually, Rip Torn—who understudied Chance on Broadway, when he played Tom, which he repeats here—is closer. But Torn is also terrific as Tom.

CK: You’re right about Newman to a degree—the character comes from the wrong side of the tracks, and although he needs a sort of exquisite beauty to make him believable as a hustler, it’s somewhat more interesting if he doesn’t look like a Midwestern football star. Chance wants to be a legit actor, but he ends up as a gigolo… it undercuts his lack of success if he’s played by the leading man of the moment. I’ll disagree somewhat and say that Newman, to me, is good at playing a somewhat self-defeating subtext that I think works in the role and underscores Chance’s position as a hanger-on. But it’s interesting to imagine how Torn would have played it onstage. (An aside: I saw Finn Wittrock as Chance in Chicago, opposite Diane Lane and before his American Horror Story fame, and he was giving off exactly the energy you describe. It was perfect casting then, although I think he’s become a little too self-consciously creepy after spending several years as Ryan Murphy’s psychopath of choice.)

DF: To me, Chance and Alexandra represent a kind of pairing that would be seen again in several more fragmented late Williams plays: two social outcasts who find but ultimately can’t save each other. I think Brooks doesn’t get that, and it also doesn’t help his work with Geraldine Page. A critical aspect to Alexandra De Lago is that as a movie star—despite her grandiosity—she’s decidedly second-tier: a legend in her own mind. The name itself evokes the likes of Alida Valli, or sadder still, Bella Darvi (the latter sometimes called “Zanuck’s Folly”); her alternate persona, as the Princess Kosmonopolis, seems even more like imagined fakery. Williams’ play emphasizes this by giving us only her own narration to describe her career—sometimes rueful, sometimes tartly funny, but always self-mythologizing. Brooks adds unwelcome flashback sequences that are far less effective. Seen here, the implication is that Alexandra’s career is more significant, put forward further when she takes a call from no less than Walter Winchell (in the play, that unseen caller is a fictitious columnist named Miss Sally Powers). It may seem a small point, but it’s a telling one: Williams’ Alexandra and Chance are more alike than different.

CK: That would definitely align with a particularly tragic thread that runs through so many Williams plays—desperate people using each other, while at the same time entirely unable to give each other what they desire. It would be more interesting if that were the case, and it would change the weight of the play/film’s ending, where Alexandra leaves in supposed triumph. But we get the literal interpretation here. That said, I don’t think Page has ever been better on film, and honestly, she’s a lot sexier (both in appearance and allure) than I usually think of her.

DF: On that point in particular, we are fully in agreement. Great as Page is in many, many roles, if I had only one example of her, it would be this. Her combination of wit and fierceness—alongside the ability to suggest heartbreak and camp humor at the same time—is nonpareil. Honestly, in terms of screen time, Alexandra is almost a supporting role here. But Page simply storms the screens and won’t let go. You said earlier that Alexandra leaves in supposed triumph. Well, the actress playing her here certainly does! If only that were actually the end. But instead, Brooks fumbles the ball. Rather than allowing Chance his final lines, which creepily indicate his acceptance of an ugly fate, we instead get Aunt Nonnie (Mildred Dunnock, in full Mildred Dunnock mode) giving a snooty summary moral judgment: “I hope you rot in hell.” Ooops.

CK: One thing I’ve always admired about Williams as a writer is that throughout his career, and no matter how commercial the work, he was never afraid to end on a downer. That attitude is anathema to moviemaking in the late 50s/early 60s, though—so boy gets girl (Chance and Heavenly elope), the bad guy gets his, and the pretty lady swans away with her head held high. How far from Tennessee Williams’ world is all that?!

DF: Speaking of second tier female movie stars, Cameron—shall we tease out our next plan? Our brilliant editor has suggested a piece about the legend that is The Legend of Lylah Clare… and not just the Kim Novak version, but the Tuesday Weld television one! I can hardly wait…

Comments