Cameron Kelsall: I hope so, and I hope too that it will introduce Wilson’s work to a wider audience. I’d argue that he’s the most consequential American playwright of the past 50 years. If you spend as much time in the theater world as we do, though, it’s easy to forget that his work hasn’t always penetrated the wider cultural conversation. Prior to this high-profile adaptation, the only other Wilson play that’s made its way to the big screen was Fences in 2016—nearly 30 years after it premiered, and a decade past Wilson’s untimely death at the age of 60. There seems to be a popular belief that his works are too intricate and expansive for the medium, and the filmed Fences, which was based on a Broadway revival starring Davis and Denzel Washington, somewhat confirmed that by staying hidebound to its own staginess. The first thing I noticed about Ma Rainey is how it’s been slimmed down and punched up by Santiago-Hudson and Wolfe—clocking in at just 95 minutes, it hits all the marks of Wilson’s original while smartly settling into a snappier, more focused filmic style. It should serve as a model for bringing some of his other stories to the screen successfully.

DF: I absolutely concur about this adaptation’s skillful transition to the idiom of film. In fact, I also agree with some of the observations about the difficulty of adapting Wilson’s plays, though I would regretfully acknowledge that some of why we don’t see them as often as we should probably has to do with their African American themes. (I’m rather pleased that we haven’t commented on race till now.) But yes, consider the challenges of these scripts. For long stretches, Wilson’s writing can seem like realism, but that’s only the tip of the iceberg. I think of his plays as Shakespearean in complexity, grandeur, and in some cases, length. The language is gorgeous, and as often in Shakespeare, it’s poetic even if not actually poetry, and requires real skill to bring it off. That this Ma Rainey does it so effectively is a testament to all the artists involved. Indeed, both Wolfe and Santiago-Hudson are absolute masters of Wilson’s work. The latter especially, having achieved a kind of trifecta: he’s acted, directed, and now adapted the Century plays on both stage and screen.

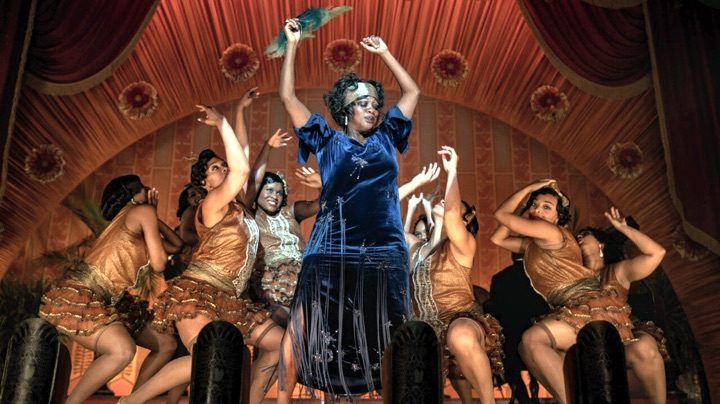

CK: Critics often describe Wilson’s writing as musical, but just as often, he literally takes music as his subject. One thing that always strikes me when I see Ma Rainey on stage is how effortlessly it evokes the world of professional music-making—not the glamorous side, but the nuts and bolts of a studio session. That’s absolutely on view here, as you can almost feel the heat rising from the tiny basement where Ma’s recording takes place on a sweltering day. But Wolfe and Santiago-Hudson go even further in a new introduction which shows Ma performing in a tent concert in the deep south. The play takes place in the early ‘20s, when old-school blues were beginning to clash with more contemporary styles adopted by Black musicians who moved to northern cities during The Great Migration. We see Ma, embodied by Davis at her most gregarious, vamping and preening in the style that made her a star. We also see her trumpeter Levee (played by the late Chadwick Boseman, in his final film performance) come downstage and steal her spotlight with a raucous solo. This invented moment sets the catalyst for the entire film in motion within a single shot—the powerful battle between old and new, established and ascendant, north and south. I think Wilson would approve.

DF: One of the things that grabbed me from the start of this Ma Rainey was the fluid weaving of the group’s performances in the South for Black audiences, alongside the Chicago recording studio (well, more a repurposed shell of a room than a real “studio”), where they are essentially visitors in a not entirely welcoming environment. That is absolutely a core backstory element of Wilson’s play, but here it comes to the fore in a way that’s vital yet still subtle. Bravo!

CK: The appreciation she receives from the southern Black audiences also contrasts with how Ma is received by the patrons of the African American hotel where she stays in Chicago—another invented scene—who seem to scorn her as she walks through the parlor arm-in-arm with her female lover, Dussie Mae (played by Taylour Paige as a barely interested hanger-on). It’s as if they look down on her and what she represents, but it also allows Ma to announce herself as unapologetically brash and unwilling to conform. That’s an aspect that will be important throughout the film, as she asserts her worth in a world run by white men, using her name and her voice as commodities.

DF: Speaking of Ma, shall we discuss that key performance? Though I’m a great admirer of Viola Davis, who is by any measure one of our finest actresses (and surely part of the reason this film was made), I didn’t see her as a natural fit for Ma. Davis’s greatest asset—seemingly infinite reserves of emotionality and vulnerability—aren’t quite right for Ma, who by all accounts was one of nature’s Tough Cookies. Davis pulls it off with a performance full of slyness and understatement, but one that signals her power at every turn. Just watch how she handles the moment when the name “Bessie Smith” is mentioned—she’s by turns sardonic, wry, but also absolutely chilling. Only at the very end do I question one of her choices—in the final scene, Davis comes close to welling up; it’s a moment where I wish she had instead remained proudly defiant.

CK: Davis didn’t entirely convince me—there were several moments where I felt reminded that she was giving a performance rather than fully embodying the character. One was Ma’s famous speech about the value of the Blues, where she seemed to be narrating someone else’s experience rather than expressing her own. But I agree that, for an actor who I think can be somewhat predictable, she takes great strides to step outside of her usual box.

DF: I do have one other reservation about Davis’s performance. I regret that she didn’t do her own singing. Except, apparently, for a few phrases within a scene where we do hear Davis, Ma’s singing is dubbed by Maxayn Lewis, who certainly does a fine job on her own. But Lewis sounds nothing like Davis. And in truth, Ma’s voice was not a blue-chip instrument—she was a great stylist and innovator, but not a vocal powerhouse along the lines of Bessie Smith, who truly was sui generis. With all of Davis’s exceptional skill, surely she could have mastered enough to do this herself. If Renée Zellweger can do her own singing as Judy Garland, I think we should expect it of Viola Davis here.

CK: I thought it was a strange choice too, though I’m not sure it’s entirely Davis’s fault. (The musical supervisor, we should mention, is Branford Marsalis.) The supporting actors are surely not playing their instruments, of course, but they all convey the energy of seasoned side men. Michael Potts and Colman Domingo both have stage experience in Wilson plays; they fit right into this world. I was especially taken with Glynn Turman, who plays the world-weary, seen-it-all pianist Toledo—a capstone to a sixty-year-career that began when he originated the juvenile role of Travis in A Raisin in the Sun. Wilson gave Toledo one of his best speeches ever—about the Black man being “the leftovers” in the stew of American life—and Turman delivers it with equal parts ruefulness and righteous indignation. I hope he’s remembered in the supporting categories at this year’s film awards.

DF: I agree entirely about Potts, Domingo, and Turman. I also thought Jeremy Shamos and Jonny Coyne contributed strong, flavorful turns in minor roles. But of course, the major performance we have not yet discussed is Boseman as Levee. As I said earlier, the play really belongs more to him than to Ma. It’s a superb role but also really tricky, since the need to evoke both sympathy and horror is quite a challenge. And in this case, everything is sharpened by our knowledge of his tragically early death, only months after completing the movie. But it’s not only sympathy that makes this so poignant—by any measure, I thought Boseman was absolutely riveting, managing the nearly impossible feat of making us sympathetic to virtually everything about him even as he made catastrophically bad decisions.

CK: I don’t think anyone will top Brandon J. Dirden in a production I saw at Two River Theater in New Jersey, also directed by Santiago-Hudson, for me, but Boseman certainly comes close. It’s hard not to read intentions into the performance knowing that Boseman died after a multiyear struggle with cancer, but it’s especially galvanizing to watch Levee rail against God and fate, as he often does, through that lens. The play’s tragic conclusion feels completely natural in Boseman’s hands—it’s a breakdown, even a mad scene, that can come across as histrionic, but here it just seems like the inevitable end of the road for a terminally troubled character. Although Boseman’s career has been cut painfully short, he leaves behind quite a body of work, and this performance is clearly his crown jewel.

DF: Nothing lessons the pain of a loss like this one, but I hope Boseman’s loved ones can take away that he left the world with not only a sensational final performance, but serving to make August Wilson’s work better known. If anything qualifies as God’s work, I’d say it’s this.

Comments