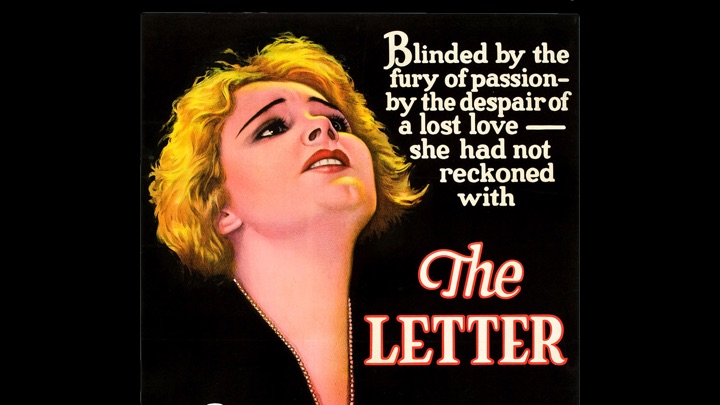

David Fox: The Remick version does seem to be findable on YouTube, but only in a dim print dubbed in Spanish, with the dialogue of course performed by different actors. I did watch a few minutes of it, and Remick seems quite different from either Davis or Eagels… or Siobhan McKenna, whose 1956 television adaptation we are also considering here. Adding to the complexity, I found a PDF copy of Maugham’s play, which suggests a couple of significant aspects that are not part of any of the three versions we watched! But I’ll save that for later. For now, as you say—it’s the legendary Jeanne Eagels in the spotlight, which is exactly the right term. From our first glimpse of her fabulous face, she seems almost lit from within… though certainly not in a saintly sense. Her Leslie Crosbie strikes me as (deliberately) the coarsest and toughest of the actresses we’ve looked at. When she repeatedly dismisses other characters as “crude and vulgar,” I silently said to myself, “well, look who’s talking, dear.”

CK: Indeed, if Davis is the model of respectable English womanhood—and McKenna is somewhere along the lines of a Douglas Sirk heroine (more on that presently)—Eagels barely suppresses the rough edges of her characterization. In fact, she seems to be plainly acting the part of a submissive wife in the film’s first scene, only coming into her true self—dominant, demanding and effortlessly violent—in her confrontation with her faithless lover, Geoffrey Hammond (played by Herbert Marshall, whom we mentioned went on to play the husband role for Wyler and Davis). To me, this duality remains throughout the movie. Eagels excels at projecting an aura of angelic womanhood in a long scene of cross-examination that appears in no other adaptation. (She’s absolutely riveting, and it’s a lesson in how early directors used their limited technical resources by focusing on her so intently, with virtually no cutaways.) But in the famous conclusion, she lashes out at her cuckolded husband, taunting him and revealing that she still has the upper hand. It’s a daring, original performance of a kind that the Hays code tried to stamp out.

DF: It’s worth pointing out that while Eagels did not play The Letter on Broadway—that honor went, rather oddly in terms of type, to the equally legendary Katharine Cornell—she (Eagels, that is) was greatly celebrated for another Maugham role: Sadie Thompson in Rain, a prostitute who resists redemption. Watching her here, it’s easy to imagine why that performance garnered such lavish praise. I do think what Eagels offers in The Letter isn’t quite right—it turns the play into a genre piece about a woman marrying above her class, and ultimately not being able to make the grade—but it’s certainly a tour de force. The movie looks, frankly, as clunky as you’d expect from a piece of its vintage (1929), with several unnecessary additional scenes, and others that are missing. But when Eagels is on screen, you certainly know why she was a star, and why her early death—at 39, of what was likely the ravages of acute alcoholism—was such a loss.

CK: The ‘29 Letter may be no great shakes in terms of technical prowess or ultimately cohesive storytelling, but it certainly beats the 1956 adaptation that aired as part of the Producers’ Showcase live television series. As mentioned, Siobhan McKenna—fresh off her international star-making performance as Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan—played Leslie, a very odd marriage of actor and role. McKenna is a great exemplar of naturalism in acting, and she settles uncomfortably into the melodramatic excesses of this presentation, which was also directed (blandly and draggingly, even at just 70 minutes) by Wyler. Her opening murder of Hammond is so histrionic it almost produces guffaws, and she never seems entirely comfortable inside the character. Ultimately, it remains a rather showy, but empty, performance, the kind you often see when an actor is miscast.

DF: So many things about this version are disappointing and mystifying, starting with the choice of McKenna. As you say, she was very celebrated for her work in Irish theater, and her film roles tend to emphasize (as of course, Saint Joan on stage did, too) a kind of sanctity. She actually plays Mary in Nicholas Ray’s camp-fest version of King of Kings! Here, McKenna sort of looks and sounds like Glynis Johns on an off day. The adaptation certainly finds a Sirk-ian undercurrent in The Letter—the clenched, wealthy wife whose seething inner passions are unrequited—but it’s mostly just dull. I find it nearly impossible to understand how Wyler—whose direction for Davis is a miracle of haunting, glamorous detail—could look so ordinary. If it wasn’t already dead on arrival, this film would be killed by the insertion of what looks like education film clips from a travelogue about Singapore, drily described by an unseen narrator. Under the circumstances, it’s not surprising that John Mills (as Robert, the husband) makes almost no impression at all. I did, however, like Michael Rennie quite a lot as Howard Joyce. But really, Cameron—aren’t we burying the lede??

CK: Yes, and it’s an occasion for joy and sorrow. This version of The Letter marks one of the final screen appearances of Anna May Wong, playing—of course—the Chinese woman that Leslie’s lover takes up with. Wong returned to the public consciousness earlier this year when Ryan Murphy featured a highly fictionalized version of her in his Netflix series Hollywood—one that garnered a fair amount of criticism for painting a rosy revisionist portrait of her struggles with racism and exoticization in the film industry. That’s a conversation for another day, although it dovetails with her performance here. On the one hand, she is a remarkable presence. She manages to steal every scene she’s in on personality alone, with barely any lines. She completely overpowers McKenna in their brief scene together, as she should. On the other hand, it’s depressing to see an actor who crusaded in her own way for the accurate representation of Asian characters on screen once again reduced to a “dragon lady” stereotype. Wong would be dead within 5 years, having never realized her full potential.

DF: As you say, even in this rather unfortunate role, Wong is riveting, her face still one of the marvels of film. The way the character is handled here is another mystery to me about Wyler—he had given such a sense of dignity to that character when Gale Sondergaard played her, but here he resorts to a lot of embarrassing clichés. For all that The Letter could be dismissed as melodramatic kitsch, there are actually quite a number of intriguing aspects to it. Not least of them is how far all these versions deviate from Maugham’s original. The Davis has a ludicrous, tacked on ending that was clearly necessary to placate the censors, but spoils the moment. The Eagels has a dreary opening conversation that almost kills it from the start, where Maugham (and both Wyler versions) use the fabulous device of starting, shall we say, with a bang. But Leslie’s famous curtain line, though heard in all three, is very different tonally from what Maugham clearly implies—that it’s a moment of comeuppance for a woman whose life will now involve the penance of playing a devoted wife. The context of the play gives her a kind of ironic dignity, which also must have worked well for Cornell. I guess we’ll need yet another version to see it all in place.

CK: If only the recently departed Olivia de Havilland had played Leslie Crosbie! She would have been much better casting than McKenna. But alas, she didn’t. She did, however, team up with Davis for Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte, which will be our next topic of discussion.

Comments