When asked what it would take to make them return to live sports events, the respondents overwhelmingly stated that a COVID vaccine would have to be widely available in order to make them feel comfortable attending a sporting event in person. Even then, 25% still would refrain from attending events. Other measures such as mandatory masks, increased distance between attendees or a marked decrease in new cases inspired much less confidence in returning. I would imagine that a survey of operagoers would display even more caution with respect to attending.

Finally, one last item in last Tuesday’s news dump came from the CDC which reported on a tragic “super-spreader” event back in March – an extended choir practice in Washington state. 61 people attended a 2.5 hour choir practice at which one COVID infected individual participated. Of the other attendees 52 are thought to have contracted COVID at this event. Two have died. This suggests how dangerous performing can be in situations such as a traditional staged performance where social distancing is impossible.

So, what options does this leave for the Met and the other performing arts organizations trying to envision restarting performances in the fall? It is clear that the most optimistic timetable for a vaccine to be widely available (and administered in enough quantity to provide herd immunity) is sometime in 2021. Even if new cases are at low levels in the fall, there will mostly likely continue to be social distancing restrictions in place. Is it worthwhile to attempt to offer live performance under these circumstances?

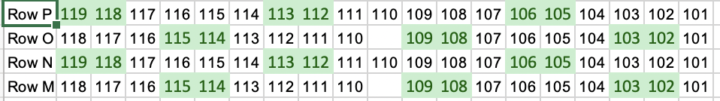

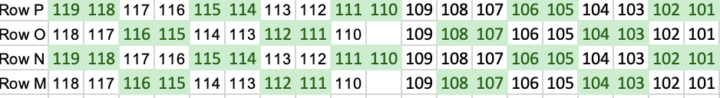

While we don’t know for certain what restrictions will be in place, I imagine that there will be some modified form of social distancing guidelines. Patrons will be required to wear masks, buy seats in pairs and stay in their assigned seats. At least half the seats would have to be empty, as shown in the illustrations below.

A possible model for “strict” social distancing in theater seats.

“Modified” social distancing: still a lot of empty seats.

Even then, there would be serious logistical challenges getting people into an orderly line to enter the theater, pick up tickets and get to their seats while staying apart from other patrons. It would easily take double the normal time to fill the theater and much longer than usual to empty it as I assume it would have to be emptied one row at a time.

The logistics of allowing patrons to use the restrooms would be formidable, not to mention trying to limit the number of people in the elevators at one time. To be honest, this seems insurmountable in a theater the size of the Met with its elbows-out audience base, but if the Met does decide to do this social experiment, please let there be a documentary crew on hand to film it.

And these audience restrictions do nothing to keep the crew, house staff and performers safe. Would the orchestra and performers have to be arranged spread across the stage in a formation that would certainly challenge ensemble cohesion? Or would anyone working a performance have to get rapid tests on the day of each performance or rehearsal? Where would singers who weren’t from the New York area stay and how would they get to New York City in a low-risk way? Would everyone working a show have to drive or walk?

Finally, if these are not obstacles enough, there is the issue of cost. A venue could only hope to recoup half its normal ticket revenue, at best. Furthermore, there would be substantial incremental costs for deep cleaning, ongoing testing and crowd control. To be honest, trying to give any performances while social distancing guidelines remain in place at a venue the size of the Met seems a non-starter.

While the Met has not yet cancelled the fall season, they have all but acknowledged that the fall season cannot go on as expected. Normally, the Met uses the months of July and August for tech rehearsals for new productions. These are essential steps in the new production process as this is the only time to work out lighting and scene changes.

Even if those rehearsals could happen, it would mean rehiring all the furloughed crew members. I doubt that crew members would return to work if the members of the other unions at the Metropolitan Opera weren’t also reinstated. This makes summer rehearsals a financial impossibility. Also, these rehearsals require the presence of the director and designers involved in the production. If travel to New York City is still viewed as risky, then that would also prevent rehearsals.

Is there another approach for fall performances? To look outside of the operatic realm, baseball and basketball seasons will take place without spectators, if the necessary agreements can be reached with the still-skeptical athletes. Sports teams have two substantial advantages over performing arts companies. First, the number of players, coaches, umpires, and venue staff required to hold a game is much less than the personnel needed for even a modest opera performance. Traveling teams could be kept isolated for the duration of a series.

Secondly, sports teams have an established broadcast revenue model with around half of a team’s revenue coming from broadcast rights. Broadcast revenue could be sufficient to make a season financially viable, perhaps with some reduction in player salaries.

Is there a broadcast-only model for a performing arts company? Well, Netflix or a television network is not going to pay an opera company the many millions of dollars necessary to make online only performances financially viable.

One approach could be for the Met to offer a set of live performances held during a special season available as an upgrade fee to its Met Opera on Demand service or via iTunes, Amazon Video and other similar distribution channels.

This “season” could start with recitals or vocal performances with chamber ensembles (which could be filmed outside the Met) and then gradually move on to concert performances or even a simplified staged performance as the pandemic situation continued to improve and health protocols were developed and finalized. I think Met subscribers and opera fans might spend $100-$200 for such a season in part because it would support performers and not just the company itself.

However, there are multiple obstacles. The first is finding the right health and safety approach. Will performers and crew consent to frequent testing? What about personnel who might be in higher risk categories? I do believe workable testing and travel protocols can be worked out once New York City has made it through several stages of re-opening. This is why I think only recitals can work to start. Even a mobile phone can do a great job of recording a performance with the right external microphone and a few ring lights.

Next are the financial obstacles. For the venture to be self-funding, it would need to raise at least $100 million in revenue, possibly more depending on the schedule and overhead charges from distributors. The actual costs would depend heavily on the agreements to be worked out with the Met’s unions and the movie theater distribution companies that may already have exclusive rights to initial “airings” of live material presented by the Metropolitan opera.

How should the stagehands, orchestra and chorus be paid when they are doing several rehearsals and a performance each month as opposed to the much larger workload a normal season would entail? A devoted Met fan might spend $100 -$200 for the subscription. But could the Met sell a million subscriptions? Probably not.

httpvh://youtu.be/GrFGBP_HbyE

So, they would need subscription tiers. Maybe $100 to view each performance an unlimited times over a 48 hour period; $250 to “own” all the performances; $1000 for a season with autographed playbills; $ 5000 for a two minute zoom with one performer over the course of a season. This would still be a great bargain as many family members could attend together.

Could that work? The Met would be competing with the hundreds of live performances already available on YouTube, DVD, and its own OnDemand service. The Met would need to count on lots of goodwill from a lot of opera fans at a time when other performing arts companies will certainly be launching similar efforts and many operagoers will be unemployed themselves.

Also, it’s not clear who would headline these productions. Would any singer fly into New York City for a week’s worth of work under these circumstances or would the Met need to pay for private jets or long-distance car services? Where would the singers stay? What repertoire would they perform? It wouldn’t make sense to stage a production with lots of supers and animals and it wouldn’t make sense to sense those same productions with the supers and animals removed.

A near-empty crowd for Act II of Bohème would make sense, pandemically speaking, but might not provide much of an escapist thrill. In the end a couple of rare-ish operas with one chestnut could work well. There’s lots of Handel, Philip Glass, and bel canto works to choose from. It might be the best way to avoid comparisons with previous filmed Met performances. Maybe, the Met could even commission a few short works.

I do think there’s a way to make a very different sort of season work while presenting performances that seem aligned with the Met’s overall brand. Do you think it could happen or is this just a desperate quarantine fever dream?