And what a glamorous event it was! As I ascended to the Family Circle, dazzled by a whirlwind of sequins and brocade, I brushed shoulders with the city’s haut monde, all dressed up to the nines to hear the much-anticipated all-Puccini and all-Anna Netrebko extravaganza.

Next to all this offstage opulence, Franco Zeffirelli’s set for Act I of La Bohème (which seemed to be missing a few Parisian rooftops, presumably to aid in the set change) looked positively drab. The singing for this act, too, was rather lackluster for the most part. All the comic business between the bohemians – which eats up the bulk of the act – lacked the energy and effrontery that the complex ensembles demand.

Quinn Kelsey, Davide Luciano, and Christian Van Horn, singing Marcello, Schaunard, and Colline respectively, were musically and vocally solid, but played it very safe. The entire first half of the act lacked any sense of freshness or spontaneity: it often felt as if the singers were simply going through the motions, and lines that should have been jocular or sprightly were often rather blandly delivered.

This was not the case with the Met Orchestra, who, under the baton of Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conjured a luminous soundscape which seemed almost at odds with the dreariness of the onstage action. In his first year or so as the Met’s music director, Nézet-Séguin has shown a proclivity for transparent textures, razor-sharp gestures, intensified orchestral colors, and amplified inner-voice dissonances.

This performance was no different, with Nézet-Séguin eschewing romantic bloom in favor of lucidity and conviction. It was almost as if Nézet-Séguin had turned Puccini’s score inside out, exposing its vivid, restless underbelly and bringing to the fore all the fluorescent, bright-hued countermelodies lurking beneath the surface.

Although Nézet-Séguin maintained a relatively brisk pace, his interpretation never sounded rushed, and he was not afraid to abate the tempo for dramatic effect. One such moment arose in the fleeting passage when Schaunard mentions the aromas of the Latin Quarter (“Quando un olezzo di frittelle imbalsama le vecchie strade”), which Puccini underpins with parallel chords foreshadowing the opening the second act.

This moment was taken at an exceptionally slow tempo, allowing us to relish the sumptuous orchestral timbres which the composer has crafted: flutes, playing in a remarkably low register, sounded positively haunting above silvery violas and iridescent rolled chords in the harp. This moment, which I had always considered to be a bit of Leitmotivic kitsch, gave me chills, and I am still reveling it, replaying it in my mind two days later.

In all three of the acts chosen for this gala, the audience is forced to wait for the Prima Donna to make an appearance, and it seemed that anticipation (palpable in the tense atmosphere that gripped the family circle) was high in the lead up to Mimì’s entrance (this was no doubt heightened by the news that Netrebko had pulled out of her last performances of Tosca at La Scala days before).

When Netrebko finally graced the stage, however, she was quiet and unassuming, even for a Mimì. Indeed, her performance was, initially, somewhat muted, and she seemed almost weary as she searched for her lost key.

If Netrebko’s Mimì seemed a little weather-beaten, it was mostly owing to the maturity of her voice, which has darkened considerably in recent years. Although the act still fits snugly in her range, the opening of this scene sounded all too weighty and labored for the coyness of her lines.

As she sang the line “Il primo bacio dell’aprile è mio”, you could almost feel the effulgent glow of the April sun shining through Mimì’s window in the fiery gleam and chocolatey splendor of Netrebko’s voice.

If all this fire began to sizzle out during the duet, this was not the fault of Netrebko’s Mimì; Matthew Polenzani’s Rodolfo – which, sadly, paled in comparison – never quite elicited the vigor needed to match Netrebko in “O soave fanciulla”. I have heard Polenzani sing Rodolfo twice this season and found him to be both vibrant and charming; however, in this performance, his Rodolfo felt a little trepidatious, lacking some of the sheen that it had in these earlier performances.

Polenzani’s performance was mired by cracks and wobbles, and he frequently encountered intonation issues in the upper register. In “Che gelida manina”, he didn’t quite seem to be on the same page as Nézet-Séguin, and Rodolfo’s surging phrases sounded too cautious as a result.

Yusif Eyvazov fared much better in Act I of Tosca, bringing plenty of luster and energy to his Cavaradossi. The tenor’s lively onstage presence added a genuine sense of danger to his seditious machinations with the rich-voiced Kyle Albertson (making a robust Met debut in the role of Angelotti.)

I have seen both Eyvazov and Netrebko perform separately before, but this was the first time I had seen them onstage together (although I had heard stories of their onstage chemistry). I was still ill-prepared for how unabashed eroticism of this performance from opera’s most famous offstage couple: they brought a latent sexual tension to the stormy lovers, so refreshing after the complete lack of spark between Netrebko and Polenzani.

Netrebko balanced the drama and camp of Puccini’s heroine, capturing both Tosca the flighty diva and Tosca the tormented lover. Her jealous ramblings were matched with clipped, biting articulation and a thunderous chest voice, while her more tender phrases had a flirtatious, playful quality. Scooping portamenti, which might have sounded tasteless in the hands of an inferior musician, became powerful expressive tools for Netrebko, adding punch to Tosca’s theatrics

Indeed, Netrebko proved adept at playing to the back row, tossing her turquoise shawl and defiantly grabbing Cavaradossi’s paintbrushes as she stormed around in envious rage. Yet it was not all fire and flamboyance: tasteful moments of yearning pianissimo, carefully poised at the upper passaggio, brought a poignancy to her “Non la sospiri, la nostra casetta”. After such a superior performance, it will be very exciting to hear how Netrebko treats the second and third acts later this season.

Sadly, the act ended on a bung note, with Evgeny Nikitin’s plodding, benign Scarpia creating a musical and dramatic nadir. His performance was devoid of the snarling villainy or menacing charm that the role calls for, and his singing lacked musicality, with many phrases sounding leaden and awkward. Fortunately, the Te Deum was rescued by a radiant blaze of sound from the orchestra and chorus, recapturing some of the vim and verve which Netrebko and Eyvazov had created earlier in the act.

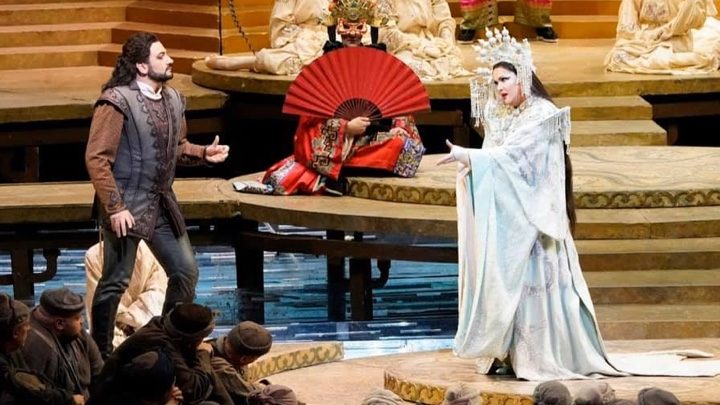

All of this was overshadowed, however, by an explosive rendition of Act II of Turandot. Netrebko’s performance as the eponymous princess was a musical and dramatic triumph, a feat of remarkable artistry, utterly thrilling from beginning to end.

Her Turandot was no frigid ice-queen, but a complex, multi-layered character, with emotions worn well and truly on her sleeve. Her “In questa reggia” was the highlight of the evening, at once vulnerable and unyielding, visceral and elegant, intimate and larger than life.

The entire act sat perfectly in Netrebko’s voice: the soaring high-register passages were fierce and glossy, and blended perfectly into her gutsy middle voice. Daring musical choices paid off in strides, including a slight rubato towards the ends of phrases which elongated Puccini’s already-lengthy lines.

The level of control that Netrebko was able to assert over this notoriously difficult act was astounding, a testament to an artist who has worked so carefully throughout her career to preserve herself for such treacherous roles. This assuredness translated into an effervescence, with Netrebko displaying her ability to take command of the Met stage.

Once again, Eyvazov rose to match his wife’s performance, delivering a determined, lusty Calàf who seemed genuinely enraptured with the princess. I had seen him in this role earlier this season and found him a tad muted alongside Christine Goerke’s emotionless Turandot.

This was not the case in this performance: every phrase seemed to be turbo-charged, endowed with an immutable electricity and his sound was open and buoyant. When he sang in unison with Netrebko, it was spellbinding – exquisitely blended and perfectly tuned.

Between Eyvazov and Netrebko onstage, and Nézet-Séguin in the pit, this was a truly magical performance, a glorious showcase of some of the most prolific operatic talents of our age. This performance was so vivid and striking that, even from my humble perch in the family circle, it felt like I was right in the middle of the action, enveloped in the sound and engrossed in the drama.

Although the gold glitter cannons detonated at the end of the act were an ostentatious reminder that this was a celebration of the new year, it seemed that the only words on anyone’s lips as the audience filed out of the theater were “Viva Netrebko”.