Unlike Gelb’s favoured directors, like Bartlett Sher or Mary Zimmerman, Carsen has not been prominent in Gelb’s focus on theatrical values. His brilliant Falstaff only made its way to the Met when Des McAnuff was uninvited from the assignment after his dour Faust. And this sumptuous and humorous Der Rosenkavalier came about because soprano Renée Fleming chose him to direct the vehicle of her sort-of farewell to the company.

Carsen has had two other successes at the Met during the Joe Volpe era. His Eugene Onegin, booed upon its arrival and mourned after its departure, was his only production exclusively commissioned by the Met. His other Met work was his well-travelled Mefistofele, which was staged as a star vehicle for Samuel Ramey. I can’t think of any of Gelb’s favoured directors who have batted four for four. I can only hope that talks about a future engagement are in the works.

Carsen has a penchant for setting productions during the time of the composer’s life. Here, he has imagined the society of Strauss’s sentimental look back through a fin de siècle lens, with the Great War looming overhead.

I was immediately impressed by the high luxurious walls of Paul Steinberg’s set, resplendent in deep reds. The elegant three sets of double doors to the Marschallin’s bedroom delight the eye. The second act set is all black and white with the exception of the bronze colours of the ostentatious Greek wall art, looking both expensive and gaudy. And in both the first and third acts, he hides the main set behind a wall which creates a contrasting, shallow playing space.

We first meet Octavian in this space when he sneaks out of the Marschallin’s bedroom for a cigarette, basking in a moment of youthful afterglow. The wall is used most effectively in the final act. It descends to show Ochs departing the inn, pursued by debtors, and then ascends again to reveal Octavian and his two loves suspended in deep thought. This isolation serves to foreshadow the effect of the great trio.

Brigitte Reiffenstuel’s costumes are as luxurious and chic as the sets, flattering the singers, regardless of body type (a feat which has evaded many a costume designer).

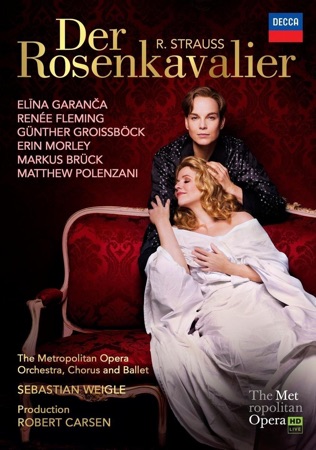

This production was the occasion of two celebrated singers bidding adieu to signature roles. Fleming, the Met’s beloved and most bankable star, was saying goodbye to the Marschallin, while leaving the door open to future appearances in less conventional work. And Elina Garanca, portraying the title character, was saying goodbye to pants roles while moving into more dramatic ones.

This video release (on Blu-ray and DVD) is from the HD broadcast which also happened to be the final performance of the run, becoming a true souvenir of their farewells.

Both artists were able to say goodbye while still on top of their game, though Garanca’s work pays more dividends. The voice has grown and developed a slight hardness of tone at the very top, leaving behind the youthful bloom of the ideally voiced Octavian. But it is still a first-class instrument, suave and even in tone throughout, and utterly suited to Strauss’s music.As for portraying a young man realistically on stage, I cannot think of any better work in a pants role, so convincing is her body language. It’s a credit to her acting that she looks awkward and unattractive as Mariandel in the first act, despite being a beautiful woman off stage. As well as being convincingly boyish, she suffers adolescent love affectingly. One can believe that she loves no one but the Marschallin even while knowing the she will fall in love with someone else in the next act.

Fleming timed her farewell cautiously, playing it on the safe side (there have been complaints over the years of her saving her voice too much, and only letting it go in the big moments) and is in excellent voice here. There is wear in the instrument but it was so plush at its best, that even with wear, it sounds better than most in their prime. Musically and stylistically, she is completely at home in a role that has served her well for years. She receives a great sendoff from the audience who applauds her first entrance and showers her with a warm ovation at the close.

I cannot say that her dramatic work is as satisfying as that of her colleagues. Though she lived with the role for many years before this production (having also appeared in the Met’s previous HD of his opera), hers is not the revelatory work of one who has achieved deep understanding of a role over the years.

Fleming’s Marshallin is dignified and sympathetic without projecting complexity. There’s no sense of irony in her performance. When telling Octavian about the passing of time, she is too much of a victim and not knowing enough; she suffers too much in front of her young lover. She is touching when on stage alone at the end of the act, as a Marschallin should be, and again when seeing Octavian move on in the third. She looks stunning in her final entrance and projects easy authority, but lacks true charisma.

This is a moving performance but the emotion is too straight-forwarded. The Marschallin is one of the most three-dimensional characters in opera and is most effective when she’s given a nuanced mix of emotional depth and a knowing understanding. Her loss of Octavian is more interesting when the angst is revealed behind a layer of self-deprecating irony.

Singing the role for the first time at the Met, Günther Groissböck steals the show as Baron Ochs. This is simply one of the great role assumptions of our time. There are many things going on in his acting all at once. His body language projects a mixture of arrogance and clumsiness, sex appeal and vulgarity. All this has the effect of appearing both studied and spontaneous – the work of an artist who has put considerable work into his preparation and is able to deliver the results with breathtaking virtuosity.

Groissböck has the kind of thick, mellifluous bass voice that one associates with this music. He doesn’t have epic low notes, but he does a respectable job of the famous low E at the end of the second act. And he hits the low C in the first act, even if not landing quite low enough on the pitch.

But he also reminds one that the role has plenty of high notes too, all of which he nails. In between the role’s vocal extremes, he sings stylishly and smoothly. His command of the text is simply superb and he tosses off one wordy passage after another with insouciant ease.Everything about Erin Morely’s Sophie is effortless, from her ingénue charm to her floated, silvery high notes. She is pert but sincere. And her innocence does not prevent her from projecting strength and independence. At one point, she is thrown to the ground and though one feels for her, she is not pathetic. She and Garanca have lovely, natural chemistry throughout.

The supporting cast is all strong. Markus Brück is a firm-voiced and commanding Faninal. Alan Oke and Helene Schneiderman hit all the marks as the wily Valzacchi and Anina, with Schneiderman particularly delightful in the third act. A previous house Abigaille, Susan Neves makes the most of Marianne Leitmetzerin after having first sung the role with the company in ‘93. Scott Conner is an appropriately stern Police Commissioner.

Matthew Polenzani’s slightly goofy, unglamorous Italian Singer’s delivers the difficult “Di rigori armato il seno” with typical musicality and technical aplomb. He is made up to resemble Enrico Caruso and his star status is highlighted by Peter Van Praet’s and Carsen’s lighting and the reactions of the others to his performance. The first verse is a fleeting moment of beauty, frozen in time amid all the clutter.

Conductor Sebastian Weigle (stepping in for James Levine) maintains a light touch, not letting the score get bogged down by its abundant orchestration, while letting the Met Orchestra delight in its many details. But there is room for more depth here. For example, I would have liked a more sardonic bite in Ochs’s entrance. He supports the singers expertly and indulges Fleming while holding things together.

Carsen’s direction is meticulous, giving loving attention to all the details. The various visitors to the Marschallin’s chambers are all given their due. The Marschallin’s and Octavian’s final interaction in the first act is thoughtfully handled. Octavian is overly aggressive in trying to kiss her, his clawing verging on violence, and she is momentarily repulsed before quickly recovering. His behaviour and her resistance explain why the Marschallin doesn’t kiss him before she goes.

In the second act, Carsen makes the interesting choice of shrouding the intimacy of Octavian’s and Sophie’s first meeting with the formality of a number of couples waltzing behind them, sometimes echoing the young lovers’ movements. The youngsters are always being watched while still having an intimate moment.

The opera’s third act can be tedious if not handled well. Here it is not only handled well but made a strength of the production. Carsen has chosen to set the act in a brothel, with the Innkeeper (a scene-stealing Tony Stevenson) a madame in drag. There is genuine comedy in the brothel action, giving a long opera welcome levity in its final act.

The portrayal of airiandel can also add to the tedium of the third act if the singer chooses to whine her way through her lines in a child-like voice. Garanca is anything but tedious. Instead of delivering her “Nein nein” in an affected voice while making googly eyes, Garanca looks and sounds like Marlene Dietrich. And she has fun throughout the sequence without resorting to coarse humour. Interestingly, when on the receiving end of aggressive sexual advances, Ochs is uncomfortable and reticent.The ending of this opera has drawn attention and I’m not entirely persuaded by it. During the final measures when the page Mohammed (here a teen rather than a young boy) typically runs on stage to fetch a handkerchief, we see him traipsing on stage drunk and swigging from a bottle. Behind him, an army proceeds towards the audience with one of the large cannons previously seen in Faninal’s house.

On the final notes, Mohammad and the army collapse to the ground. This gesture is meant to close the loop on the notion of a society on the brink of war and devastation. While I do no object to the concept, I find the execution unconvincing. The frothy music is at odds with the notion of impending war and there is not enough music to allow the idea to be fully realized.

One of the most striking features of this production is the presentation of Baron Ochs. Physically, Groissböck is not the typical man cast as Ochs. He is handsome and well built. He doesn’t have a big belly and there is no attempt to give him a fake one. The opposite is true. At the end of the second act, as he’s recovering from his injury, he dresses down to his undershirt, revealing bulging biceps. Yet, he is as repulsive as any Ochs because of his behaviour, not because he’s old and fat. This modern take on the character proves even timelier than was probably intended.

Since the accusations against Harvey Weinstein and the rise of the #metoo movement, operas with sexism and misogyny in their storylines are being viewed in a different light. In Le nozze di Figaro, the Count’s behaviour towards his wife and the women in his employ was always to be disdained by the audience, but now has an extra resonance.

This production preceded the #metoo movement, and Groissböck’s take on Ochs preceded this Carsen production (first seen in Harry Kupfer’s 2014 Salzburg production). But by putting the focus on his behaviour rather than his physical appearance, this production is particularly resonant and the timing of its recent video release makes this interpretation all the more timely.

What struck me as I watched this production is how it belies some of the clichés that people have about opera. Here is an old-fashioned story, in a piece that looks back more than forward, with the title character a pants role. Yet, watching the vibrant performances and the deftly directed action, I was often impressed by how contemporary it all felt.

There is no park and bark, no banal gestures. Singers look at each other when addressing one another; they listen when not singing themselves; and no one’s eyes are peeled on the conductor. A non-opera fan could watch this and laugh out loud, or get swept up in the adolescent romance of its young lovers, and feel repulsed by the brutish Ochs – without experiencing any of those things at an artificial distance that can sometimes be a by-product of opera.

If a measure of a production’s success is that it presents the opera in a relatable, engaging manner, then this production is a triumph. Here’s hoping that Carsen is given an opportunity to continue his perfect batting average.