As distasteful as it might be to say, it is difficult to live with the sick and suffering. Mortality is ugly—it smells, it makes uncomfortable noises, it takes its time; and then there is the overwhelming sense of dread and helplessness. Fate often only gives one choice: observation. We hold hands with the sick, we watch, and we wait with them.

Our obligation to the dying is a question taken up by writers throughout the history of literature. Sophocles explored it early on with his play Philoctetes. And Tony Kushner investigated it with acute horror in his two-part play Angels in America, as the character Louis abandons his lover Prior, who is dying of AIDS. The moral question of what we owe the infirmed weighs heavily on Louis, who ultimately cannot forgive himself.

How does one abandon someone they love, especially when they are most needed? How do we remain present, despite our lack of agency, the overwhelming aversion to illness and death? For Rodolfo, the problem is too difficult to bear—it is beyond the scope of what he can endure. He returns to Mimì, and they decide to wait until the spring to part, staving off their separation. They choose to wait for sweeter weather

Despite Puccini’s romantic, sweeping music, it’s important to remember that La Bohème is not just about Eros; it also focuses on poverty and sickness. While we admire the artists in the garret, living fully actualized lives day to day, it is significant that their lack of resources is the crux of their tragedy.

Mimì’s illness cannot be successfully treated in her economic condition. She lives as best she can, in poor health, a slowly sinking trajectory toward death. It is only through startling bursts of color and light, attending her experiences of romance, in which she finds any escape from her unbearable situation.

Franco Zeffirelli’s famous 1981 production at the Metropolitan Opera, which plays its last performance this season on January 14, frames these ideas with picture perfect imagery. It feels as if we are looking at a postcard of these events, but not probing the realities of these experiences. Even the drab garret has a touching, romantic feel to it, suggesting adventure and intoxication, but doing little to explore the costs of such a life.

While the set has all the makings of poverty, it doesn’t quite evoke the desperate feelings provoked by destitution (indeed, I’m certain many denizens of Manhattan would love to have so much space.) While Puccini’s music, conducted at this performance with touching sensitivity by Carlo Rizzi, concocts a heady atmosphere, the Met’s production fails to contextualize this romance within the confines of economic marginalization.

In the central role of Mimì, Ailyn Pérez was relaxed and natural, though it would have been nice to see more anxiety rising to the surface. Her beautiful, plush soprano evoked the plaintive, internal qualities of Mimì’s character, though her radiant beauty made it a little difficult to see her as ill.

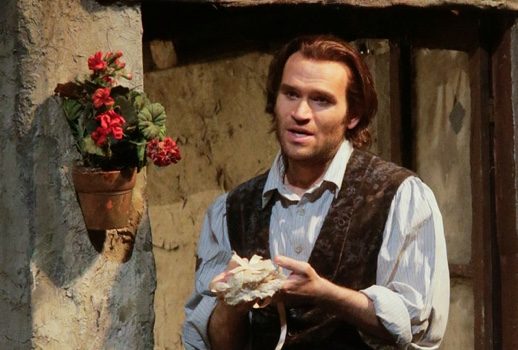

Alessio Arduini was a sexy and virile Marcello, in a quirky sort of way. His baritone has a smooth, consistently rich sound; and much like Pérez, his approach to the character is warm and unaffected.

As Musetta, Susanna Phillips didn’t quite muster the necessary flamboyance, missing the vitality, ebullience, and passion of the role. Her voice has a pleasant vanilla quality, which didn’t quite detract from Musetta’s dramatic sensibilities, but didn’t quite boost them either.

As Colline and Schaunard, Christian Van Horn and Alexey Lavrov rounded out a young and good looking cast with well-produced singing and effective dramatic work. Van Horn was especially noteworthy for his “Vecchia zimarra” in Act IV.

No, money can’t make you happy. It can’t prevent death. But, in the long run, it certainly helps. And while it’s difficult not to romanticize the situations these bohemians find themselves in, we must also remember that the opera is, in the end, a tragedy. As Puccini’s final chords indicate, all does not end well for Mimì. As the curtain falls, one wonders how things might have been different if she possessed more financial resources.

As the New York Times reported yesterday, the United States Senate is taking its first major steps in repealing the Affordable Care Act today, making very real the uncomfortable prospect “that millions of Americans could lose health insurance coverage.” The major themes of illness and poverty that drive the plot of La Bohème are still very much with us.

One wonders at all the lives that might flourish under different circumstances, the Mimìs of this country who live hand to mouth. What is our responsibility to the sick and suffering? With this question in mind, the ending of Bohème might signify as a contemporary cautionary tale, instead of an inevitable tragedy.

Photo: Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera