In Puccini’s massive musical landscapes, all participants—singers, players, conductor, production designer, and even lighting designer—must feel the work in concert with one other, identifying and emphasizing its climaxes, ebbs, and points of inflection. Otherwise it risks becoming—as Arnold Toynbee described the drudgery of everyday human existence—“one damned thing after another.”

The near total success of the San Francisco Opera’s current run of Jun Kaneko’s production of Madama Butterfly came down to this one factor: the people behind the production understood how to make sense of Puccini’s musical immensity. While such a success requires the investment of every person involved, the vision behind it nearly always comes from the conductor—and Yves Abel’s performance accompanying Lianna Haroutounian as Cio-Cio-San was first-rate.

Puccini’s score received a sumptuous and finely-textured reading from Abel and the SF Opera Orchestra, beginning with the string section, which for Puccini forms the dramatic scaffolding beneath the tragedy. The orchestra’s strings rose marvelously to the occasion, driving melodic lines forward and giving just the right amount of meaning and emphasis to the apex of phrases.

But the music of Butterfly relies every bit as much on leitmotiv and innuendo as it does on visceral melody. Indeed, the brief but pivotal moments in which Puccini casts the orchestra as dramatic lead showed Abel at his best—the spasm of brass as Cio-Cio-San shows Pinkerton her dagger, the organ effects as she describes her religious conversion, the muted trumpet lines as she dreams of the spires of Pinkerton’s ship on the horizon, and the subterranean clarinet and bassoon coloration of the opera’s mournful conclusion—were all performed lovingly. Fine brass and woodwind playing helped to enfold Butterfly’s many musical allusions—particularly its recurring quotes from The Star-Spangled Banner and Miyasan, seamlessly into the score.

Perhaps most emblematic of Abel’s masterful pacing was the deafening weight of the silences in the opera’s penultimate scene as Cio-Cio-San fully grasped the fact that Pinkerton would not be returning for her. In this moment, simultaneously tender and suffocating, Puccini’s florid orchestration subsides into its most elemental components—held block chords separated by pauses. Treating the silence with emphasis equal to the sound, Abel seemed almost to stop time with each pause.

There were rare orchestral blemishes: sharply-articulated, rhythmic string playing is not one of the SF Opera Orchestra’s strong suits; and while this sort of writing is somewhat rare in Puccini, it unfortunately forms the opening music of Butterfly. The orchestra’s somewhat pedestrian performance of the opening gave me the (happily incorrect) impression that I was in for a long evening. There were also occasional moments of poorly calibrated dynamic shifts later in the opera (the abrupt and cymbal-laden arrival of one swell in the love duet evoked the disruption of an intimate evening by an overzealous village band). But these few flaws served only to accentuate the finely-calibrated richness of the rest of the orchestral performance—a performance entirely worthy of Lianna Haroutounian’s deeply-felt and persuasively-performed Cio-Cio-San.

Matching Abel’s luxurious pacing, her voice floated atop the orchestra, at certain moments melting resignedly into Puccini’s woodwind doublings, and at others breaking confidently through the texture. Consistent with the aesthetic of the opera, many of her best moments showed a mature artistic restraint, an ability to postpone musical resolution as far as possible. While she poured out to Suzuki her visions of Pinkerton’s return in the start of the second act, this approach took on a deep narrative, not just musical, significance.

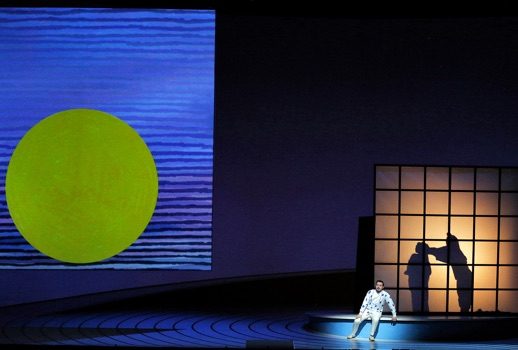

Haroutounian’s counterpart, Vincenzo Costanzo as Pinkerton, was a more than fitting partner for her high artistry in his U.S. debut. A lyric tenor with a full but soft-edged tone, he was at his very best in the wedding night duet, where he and Haroutounian’s voices interacted almost orchestrally, seeming to merge at times into a single instrument. The scene, accented by the very gradual rise of a full yellow moon on a screen behind the couple, was the high point of a production full of them (and elicited a pre-intermission curtain call). Costanzo’s nuanced acting made the contradictions of Pinkerton’s character fully believable—from the offhand quips about infidelity on his wedding day (that alerts the audience, lulled by Cio-Cio-San’s naiveté, to the opera’s tragic conclusion), to the pathetic regret with which he flees the stage in the final sequence.

Supporting Costanzo was a standout performance by Anthony Clark Evans in the role of U.S. Consul Sharpless. Delivering a rich baritone capable both of light witty repartee with Pinkerton in the first act and a solemn, almost paternal, sympathy and shame in the conclusion, Evans’ performance was a study in contrasts. It was marred by only one (somewhat jarring) lapse: in the moment when Sharpless returns to Pinkerton’s house to bear Cio-Cio-San the shocking news of her husband’s abandonment, Evans’ delivery was uncharacteristically deadpan.

His counterpart supporting actress, mezzo-soprano Zanda Švede as Cio-Cio-San’s maid, Suzuki, delivered a rich complement to Cio-Cio-San’s second act lamentations. Though occasionally overpowered by the orchestra and Haroutounian in higher range, her performance in lower alto-range material showed a golden tone.

Behind the leads, an unsung (and unsinging) hero of the production was Ian Robertson as chorus master. Marshalling a mostly backstage brigade of 35 choristers, his direction achieved exactly the level of distance in the sound that Puccini’s composition required. Robertson’s chorus provided brilliant coloristic effects, from the suspended vocal mist that ushers the guests into Cio-Cio-San and Pinkerton’s wedding, to the religious reverence of the humming chorus during her final vigil.

With memorable scenic elements, Kaneko was able to vest certain pieces and objects with an almost leitmotivic significance. For example, the multicolored streamers that hung down around the stage during the wedding scene were reprised as a set of ragged multicolored horizontal lines on a screen as Cio-Cio-San put on her wedding robe in the second act to await Pinkerton’s return. With this simple association, Kaneko built a subliminal connection between the opera’s tragic conclusion and the bliss of the wedding day, serving as a sobering reminder of life’s evanescence.

Perhaps the most brilliant aspect of Kaneko’s production was his decision to set the stage at its widest and most open during some of the opera’s most tender moments: he opts, for example, for a succession of portentous primary-colored animations during Cio-Cio-San’s overnight vigil. Even in the intimate wedding night duet, he leaves the stage mostly open, reminding us of the immensity—indeed the cruel ambivalence—of the characters’ world. At such moments, one could almost hear Humphrey Bogart’s Rick Blaine intoning from this side of the stage that the problems of two little people don’t amount to a hill of beans.

The production unabashedly embraced the exoticist aesthetic of turn-of-the-century Europe that Puccini’s audience would have taken for granted: the aromatic allure of a society so far apart from that of the composer and performers that it seemed to exist only in the imagination. While there are some productions today of works like Butterfly or The Mikado that seem to try to avoid that period aesthetic, it was an indispensable element in Kaneko’s rendering. His Japanese costumes—complete with loose-fitting robes in rich patterns and heavy face makeup—created the impression of a world apart. And his vibrant use of color and sharp angularity—box-headed, black-clad kurogo and brightly colored dress and headwear for the Japanese nobility—lent an almost mythic backdrop to the piece.

All these elements—vocal performance, orchestral accompaniment, set design, lighting, and costuming—joined forces to make this production of Butterfly a coherent and deeply moving artistic experience. But this production, at its heart, showed the importance of a sensitive and expertly-shaped performance from podium and orchestra pit in capturing the true spirit of Puccini.

Photos: Cory Weaver