So claimed the first Klytämnestra, Ernestine Schumann-Heink. The 20th and 21st centuries would have much to say about the “nothing beyond” part, but Strauss and Hofmannsthal’s bloody one-act tragedy has never left the repertory. In a good performance, it can still grip, disturb, and haunt as it did in 1909.

Elektra’s tardy 1932 Metropolitan Opera premiere was reported in the New York Times to have received 15 minutes of sustained applause. Critic Olin Downes wrote that in eight years of covering the Met, he had never witnessed such audience enthusiasm. Surprisingly, then, Elektra’s Met history remained spotty until the 1960s. Of 101 performances in the archive at this writing, 82 took place between 1961 and 2009.

On Thursday, an acclaimed Elektra (the final one described below) arrives at the Met, replacing a 24-year-old production not seen since the work’s 2009 centenary. When La Cieca suggested I write a piece comparing and contrasting the opera’s available DVDs, I was intrigued enough to accept the challenge, with some trepidation. Only two productions were unfamiliar to me, but I wanted to give even familiar ones a fresh look, not relying on impressions, favorable or otherwise, from years ago.

Fortunately, Elektra is under two hours long. No matter how this entry is received, there will be no Götterdämmerung follow-up.

Thousands of words could be devoted to any of these performances. In covering all eight, I cannot say everything I would like to say about them. I ask the reader’s forbearance, and hope the overview can make up for in breadth what it lacks in depth.

The 1989 Vienna, 2010 Salzburg, and 2013 Aix performances open only the first of a half dozen standard stage cuts, four lines for Klytämnestra as she vows to wrest the sacrificial victim’s name from Elektra (“Sagst du’s nicht im Freien”). The remaining performances exercise this cut and all others. To hear Elektra note-complete, look to the recordings of Georg Solti (Decca) and Wolfgang Sawallisch (EMI).

The earliest performance under consideration is a 1980 Met telecast conducted by James Levine, a revival of a 1966 production created by Herbert Graf, set by Rudolf Heinrich. I have no trouble believing contemporary reports that this was a good production in its day, but much in the opera world had changed by 1980, still more by 2016, so the interest here is nostalgic and anthropological more than theatrical.We get an idea of how Elektra might have been staged a half century ago, but detail is hard to make out. Television director Brian Large stays close to the singers and is stingy with views of the entire stage; Gil Wechsler’s lighting is low.

The serving women put us on notice early by lining up in stiff formation to belt out their lines. When the principals, all old pros, begin to trickle in, the performance gets somewhat more dynamic, but the revival direction is a study in caution as opposed to care.

Birgit Nilsson and Leonie Rysanek had brought their sister act to this production when it was new, and had starred in two classic radio broadcasts of it. Here, one must decide whether the glass is half empty or half full. On one hand, they were filmed in signature roles before it was too late. On the other, it was still late.

Nilsson at 61 is gingerly in movements and sounds near the end of the line, soldiering through a whiter, shriller, less reliably pitched facsimile of her classic interpretation. She has an interesting face at rest and listens well. Rysanek has more capital to spare and remains a gleaming, if mature Chrysothemis. Mignon Dunn’s good taste is a reminder that Klytämnestra as other than scenery-chewing gargoyle is not a recent discovery.

Levine’s brash conducting serves up energy without intensity. While he had already brought the orchestra he inherited a long way, there was room for improvement.

Of greater visual and dramatic interest is Götz Friedrich’s studio film, made in the summer of 1981 with a prerecorded soundtrack. Mycenae is awash in rain and blood. The inhabitants’ gray pallor suggests prolonged deprivation of sunlight. A modern factory looms over ancient ruins. We never get a clear spatial sense of this environment, and the confusing layout, which at first seems a filmmaking weakness, may be conceptual.Although one of the more successful examples of its kind, Friedrich’s film suffers from the usual problems of opera in this medium: imperfect synchronization; disconnects between what we see and hear (the Fifth Maid sings out securely while being realistically flayed); the fundamental artificiality of operatic singing coming from people who are not producing their voices.

This is, even so, gripping work from a major director. Friedrich uses the medium to flash back to the murder of Agamemnon as Elektra describes it. Noted German tragedian Rolf Boysen plays the mute role of the slain king, staring with sad eyes at his daughter. Pagan rituals are given gruesome cinematic treatment.

Although the Chrysothemis (Catarina Ligendza) is not among the more impressive in this survey, Friedrich teases out ambiguity and inner conflict in the scene of Elektra’s quasi-incestuous overtures to her. Elektra dances as though astonished to discover she can move again. At the end, she has collapsed but still blinks. Both sisters are shut out of the palace, having no place in the new order.

Rysanek undertook the title role only under studio conditions. In her time, it may not have been considered her assignment, but she sounds better endowed than some successors. She brings shimmer and float to the lyrical music, and if she does not make the rest sound easy, she makes it sound plausible. This Elektra convinces as the enthralling beauty turned harridan. The time was right for the experiment, and one can overlook a few overshot pitches. Astrid Varnay brings off a grotesque “veteran” Klytämnestra with relish and style.

Karl Böhm, near the end of his life, tends to linger and underline, not always to his cast’s comfort, but the sound of the Vienna Philharmonic in this music is difficult to resist. The eerie glow of the strings following Elektra’s “zeig dich deinem Kind” haunts the ear.

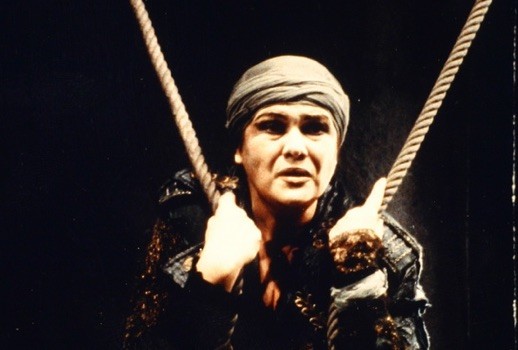

Like Friedrich, Harry Kupfer (1989, Vienna) renders the psychological chaos physical: Mycenae is regressing to a primordial state. Minor characters wriggle on the ground like specimens under a microscope. Everyone wears shapeless garb, the women are sexless drudges with covered heads, and even the queen’s garment is tattered. The one bright color is the scarlet of Chrysothemis’s chemise, which she uncovers as she sings of new life.The stage is dominated by an enormous statue of Agamemnon, its foot bearing down on a globe. The statue has been decapitated (the head is upstage), and ropes are attached to the body for leveling. Elektra clutches the ropes and never ventures far from the statue’s base—a protesting zealot.

The Orest scene, a dramatic lull in some rival versions, receives its fullest realization, and Franz Grundheber is the best Orest on any of these videos. Orest could be a traumatized veteran, returning from offstage horrors of his own.

“Er freute sich zu sehr an seinem Leiben” is the sound of a man for whom joy is a dim memory. The lines are not deceptive, one realizes: the younger Orest described is dead. Claudio Abbado and the Viennese players whisper and groan of secret, subterranean things, and early exchanges between brother and sister are muted, dreamlike (I was reminded, oddly, of the heroine’s husband stepping out of the fog in the film The Others). As haunted as this Orest is, he is better off for having been away. He retains a humanity that spreads outward to Elektra even before the recognition, which plays with real terror.

Elektra’s dance consists of grasping a rope and circling the statue. It appears she is trying to pull it down on herself to perish under its weight, but she can only bind herself to it more tightly. She dies in the exertion, crumpling against her “father.” Her sister and brother (he with bloody hands) look on.

Eva Marton’s obdurate, forceful Elektra provides a strong center, and Cheryl Studer brings urgency and heated steel to Chrysothemis’s counterarguments. The great Brigitte Fassbaender’s lunatic Klytämnestra is so rife with vocal and histrionic overstatement (“schlacte, schlacte, schlacte” intoned in camp frustration, fists pumping) that almost nothing is “stated.” Vivid it may be, but it is also wearying.

The playing under Abbado is swift and lean, with long lines uncoiling, thoughts coalescing into the bigger picture – superb. Not everyone thought so. A vocal minority boos him and Kupfer at the end.

Although Otto Schenk’s Met production was only two years old at the time of a 1994 telecast, it is little more vital than its Met predecessor. Jürgen Rose’s slanted palace/courtyard, rendered in the colors of nausea, gives the singers a cluttered area in which to move about. Like many Met productions of this era, it was more reassuring to conservative visual tastes (including those of its commissioners) than it was helpful to the performers.

Presumably the first revival director realized Schenk’s intentions, but the production fails to make something strongly unified of its participants’ disparate styles. It is difficult to see what here required a producer of international reputation to make it happen.

Recording balance favors Levine and his orchestra, which had greatly improved over 14 years. Levine’s reading is more settled, although still long on flash and bombast. Deborah Voigt was at this time a raw, awkward stage performer, but her Chrysothemis is a welcome reminder of the big, plush voice with which she began. Fassbaender’s Klytämnestra by now is impervious to parody (she has done all possible exaggeration herself), and it is less well framed by this blandly impersonal production than it was in Vienna.

Hildegard Behrens’s Elektra discloses intelligence in preparation, and there is something of the decaying beauty in her charismatic presence. She sets off a bottle rocket of a high note once in a while, but is battling a recalcitrant middle register, gritty and toneless. Her dance, full-bodied and unhinged, is the high point of her performance. We close on Chrysothemis shouting for Orest, pounding futilely on the door.

Martin Kusej was the youngest of these directors at the time his production was new (2003, Zurich; filmed 2005), and it shows. His is the zaniest of the eight Elektras, the most freewheeling, the funniest…and the most likely to infuriate traditionalists.Elektra frets over not having given Orest the ax when Orest has a platoon of ax-wielding supers in white following him (“I think they’ve got it covered,” one wants to tell her). Later, a Brazilian samba troupe invades to flaunt their plumage and wiggle their butts; Elektra leaves the dancing to the pros. There is more going on than irreverence, however. When one character admonishes another (or more than one) to be quiet, the admonishments play powerfully. There are ears everywhere.

There are other organs too. Klytämnestra and the rouged-up bear Aegisth preside over sex parties and maybe worse unseen. The serving women brandish S&M gear and change into sexy maid costumes for their day on the job. The staging area is indoors, on a floor as uneven as sand dunes. Four doors on either side and another upstage open on blinding light and ominously sterile, padded rooms (“Mach keine Türen auf in diesem Haus,” indeed). Many supers scamper through: men, women, one child.

It is the sort of production that makes you briefly wonder why someone nearly voiceless was entrusted with a small part, and then you think, well, of course: he looks good without pants.

Christoph von Dohnányi conducts cannily in consideration of the least impressive of these casts. Eva Johansson (Elektra as sullen, alienated youth in hoodie and fingerless gloves) and Melanie Diener (Chrysothemis) create a relationship of interesting volatility. I wonder if, in an earlier era, they would have been steered toward these roles. Each appears preoccupied with driving out sound; they punch through with effective “moments” but lack command and sweep.

Johansson’s “Orest! Es rührt sich niemand” is her vocal highlight, luminous and supple. Marjana Lipovsek (Klytämnestra) matches up well physically with Johansson and gamely models self-absorption, barking at underlings to leave her when they already have stopped listening and wandered off. Her mezzo, formidable in its prime on Sawallisch’s recording, was showing erosion by 2005.

By the conclusion, we may wonder how much of what we have seen was in Elektra’s disturbed mind. Kusej has considered potential meanings of “Ob ich die Musik nicht höre? sie kommt doch aus mir.” Either way, a point is made: the heathens having been smitten, one type of excess has pushed out another. Chrysothemis, who had worn white throughout, has completed a transformation to the Virgin. Elektra returns to the pose of watchful disapproval she had held at the start, rebelling against whatever they’ve got.

Herbert Wernicke’s 1997 production was revived at the Festspielhaus Baden-Baden in 2010, eight years after its director/designer’s death. It recalls an aesthetic in vogue as the millennium approached, typified by Carsen’s Onegin, Wilson’s Lohengrin, Dorn’s Tristan: abstract and spare, with limited props, the story dramatized with light, space, and bold colors, usually one dominant shade at a time.Though an artifact of its era, this is a cogent, intelligent staging, attractively designed. A large square panel tilts and pivots to expand and contract the playing area, also effecting entrances and exits. Wernicke makes much of physical distance, widely separating the characters even when two are in conversation. Follow-spots are like psychological prisons. We are almost an hour in before there is any person-to-person physical contact. Even that contrarian maid is not assaulted in view.

Elektra does not dance at all, but does fall dead (of self-inflicted ax wound) on cue. Chrysothemis looks on from a staircase, dazed. The ascendant Orest, already beyond fraternal cares, raises an arm, and one thinks of fascist salutes, although his palm is upturned.

Musically, things get off to a promising start with an uncommonly strong group of serving women. The DVD would be worth acquiring for the conducting of Christian Thielemann alone. This is one of the great readings of Strauss’s score, breathtaking in color, weight, and flexibility, with chilling silences.

From Jane Henschel, we have a golden-age Klytämnestra. She gets in her share of the traditional mugging, but in none of these performances is the role more firmly and honestly sung. It is the work of a complete musician in command of a voice with power and pliancy; nothing is cheated or tossed off.

Linda Watson and Manuela Uhl generate a very loving Elektra/Chrysothemis relationship (too healthy?). Watson had stepped in for another singer and learned the title role quickly. She cuts a stately, regal figure, well suited to a production that does not call for bounding around the stage. Up to a point, her sound is rich and colorful; low notes are steady and beautiful. Unfortunately, the part tests the less reliable top of her voice, and there are scooping, flapping, and approximate pitches on high. Uhl manages cautiously, and while she brings touching fragility to Chrysothemis, we have seen that there can be more than this.

Nikolaus Lehnhoff’s 2010 Salzburg production is all festival luxury, from the three Isoldes at its center outward. Raimund Bauer’s set is full of pits and crevices, and the palace leans backward, a proud edifice that has improbably survived some cataclysm and is still standing… just. Aegisth is in a 1940s suit, and the Overseer’s uniform evokes the SS.The familial resemblance here is between Chrysothemis and the glamorous Klytämnestra, who share coloring and favor plum tones. Iréne Theorin, Elektra as violating wraith, is almost unrecognizable, her blue eyes peering out from behind a chalky death mask under a wig of black straw.

Theorin enunciates clearly and wins some points for subtlety. More than any of the others’, her “Allein! Weh, ganz allein!” at first sounds “allein,” an abandoned child’s call in the dark. But the strongest performances are Eva-Maria Westbroek’s self-possessed, radiantly feminine Chrysothemis and Waltraud Meier’s refined Klytämnestra, a beleaguered queen overshooting the mark at keeping up appearances of vitality and beauty.

Meier does not have the vocal firepower of Henschel in the previous performance, but she does so much with words and music that it all seems new. When she sings of “der kühlen Luft,” that cool air steals through the tone—a small miracle. Her scene is an array of such expressive touches, all shaped and balanced with an artisan’s care. Lehnhoff has his Klytämnestra gradually shedding diva accoutrements (sunglasses, turban, fur) as the confrontation gets more “real.” Meier had performed similar routines for him as Venus and Kundry. The singer’s imagination this time surpassed that of her director.

Benjamin Hulett’s exceptional Young Servant has perfect rhythm and attack, and none of these Aegisths has more voice than Robert Gambill, who had been Lehnhoff’s Tannhäuser a couple years earlier. René Pape coasts through a bass Orest on suave tone. The VPO under Daniele Gatti provides a bruising, high-sheen musical framework.

As Kupfer’s totem was a statue, Lehnhoff’s is Agamemnon’s coat, passed from character to character. Rather than dancing, Elektra staggers and crawls toward the coat. A garage door opens to reveal the slaughtered queen hanging upside down. Elektra’s final act before dying is to “crown” Orest by placing the coat on his shoulders.

The production ticks all the expected boxes and a few unexpected ones—it is the only one to suggest in the closing moments what was ahead for the Orestes of Greek tragedy. There is much to admire, but a glib, fussed-over quality, with roteness to the Personenregie, keeps it from the highest level.

Each of the seven previous productions was created by an Austrian or German man of the theater. Patrice Chéreau, whose own last dance the 2013 Aix-en-Provence Elektra proved to be (he would succumb to cancer two months later), concluded with something similar to his famous 1976 Bayreuth Ring: a Frenchman’s radical rethinking of a German masterpiece.It is radical not for being shocking or perverse (next to Kusej’s, it is quite sober), but for taking nothing for granted in Strauss and Hofmannsthal’s opera. In every scene, there is evidence of fresh thought, big questions of “why” and “how” having been pondered, decisions arrived at. If something plays as it often does, it is not out of adherence to tradition but because it was the logical outcome.

What emerges is not Elektra as it “should” be done, but Elektra as it can be done, an Elektra that is special and personal. While it is unfolding, its choices seem inevitable. This is Regietheater when it works, and any aspiring director of opera should give it a close study.

Richard Peduzzi’s set is not the typical ruin, nor is it angled or distorted. It is orderly, bloodless, scrubbed to the look of clean bone. The chaos is in the people: their eyes, their bodies, their voices. This is the most compassionate Elektra I have seen, and the saddest. Chéreau grants everyone from Elektra to Aegisth down to the meanest serving woman depth and humanity. All are locked into their roles and await the consequences of their actions. To choose a side in the conflict would be like rooting for wind, water, or stone.

In a modern-dress Mycenae teeming with femininity (there are more women than there are singing parts), Elektra is, tellingly, the only woman not wearing a skirt. Evelyn Herlitzius’s singing is not flawless in emission or pitch, but no Elektra is more fascinating to hear and see. Hers is a performance of visceral intensity, so desperate and wild in vocalism and physicality that it seems pointless to separate the components.

Meier again brings discernment and elegance to Klytämnestra’s music and bearing. In collaboration with her favorite director, she finds even deeper truth than she had for Lehnhoff. When she and Herlitzius are onstage together, great drama happens; it does not even need to be qualified as “music drama.”

Adrianne Pieczonka (Chrysothemis) and Mikhail Petrenko (Orest), not as searing or as individual in handling of the text, nevertheless uphold the high standard. The murders take place onstage, and Tom Randle’s stylishly underplayed Aegisth gets a moment of horror and grief over his lover’s body.

There are great, familiar faces in small roles: Donald McIntyre (Orest in the two Met performances) as the Old Servant; Franz Mazura as an ancient, dangerous Guardian; Roberta Alexander as an incomparably moving Fifth Maid. The oldest servant, with the longest memory, her eyes brim with tears.

Esa-Pekka Salonen’s conducting of the Orchestre de Paris is unusually lithe, full of quicksilver fantasy yet not stinting on accumulated force. Stéphane Metge‘s video direction is of surpassing sophistication.

Herlitzius’s dance is that of a mad puppet on unseen strings. As the hollowness of Elektra’s triumph sinks in, the death is a psychic one. His deeds done, Orest departs, heedless of Chrysothemis’s call. He leaves behind his sisters and those courtyard hounds that had recognized and welcomed him–here, a reference to the servants.

In this extraordinary production, nothing is more extraordinary than the marriage of modern psychology to the elemental power of classical tragedy. Surely that is “what the composer and librettist intended.”

Although even the least of these performances has elements of distinction, two stand above all others, putting the most greatness in one place: Salonen/Chéreau and Abbado/Kupfer. This trip through a rich operatic videography was both an education and a great pleasure. I hope I have conveyed something of that to the reader.