“Hailed ‘the Meryl Streep of opera’…” begins one sentence of a promotional piece for a Diana Damrau recording of another opera, reproduced on the soprano’s website. This is a lofty claim, but I considered it as I watched Erato’s DVD

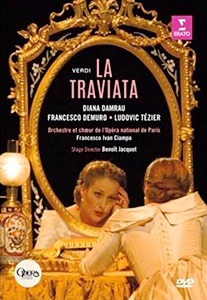

memorializing the last of five 2013-14 Traviata productions (New York, Zurich, Munich, London, and Paris) in which Damrau sang her first Violettas.

There is, of course, a superficial similarity. Both women are attractive, refined blondes with German roots, and both can appear elegant or plain as a role requires. Both impress offstage as merry women and good storytellers, engaging in conversation and interview (I remember years ago hearing Damrau talk about the role of Strauss’s Sophie, and although she joked and laughed a lot, there was nothing frivolous about her insights). Both are admired technicians and hard workers.

Above all, both women in their performances seem “immersed” without being “possessed.” They throw themselves into stage business with conviction, but they are perhaps too down to earth and too analytical for one to talk of “mad genius” or some equivalent term. It seems doubtful they experience the pains of separation some actors describe when they must let a role go and move on to the next show. They can wow you with a death scene, but you never forget it is the character suffering up there, not the portrayer.

Moments after expiring in a most convincing and harrowing fashion onstage here, Damrau takes her first bow and literally skips back behind the curtain and into the arms of Nicola Testé, her Dottor Grenvil (and her real-life husband.) No staggering around looking stricken or teary-eyed for her, with Violetta’s plight promising to weigh on her into the night. She has triumphed on the stage and she knows it, and when the last chord has passed, so has the illusion.

Damrau’s Traviata productions in this busy period, some new and some old, ranged from the blamelessly traditional Richard Eyre in London to the radically rethought Dmitri Tcherniakov in Milan. We were fortunate to have the fifth, Benoît Jacquot’s in Paris, documented.

This is not because it is the best of the bunch or a remarkable Traviata, but because Damrau appears to have taken everything she has absorbed from a range of productions into this one and arrived at something that echoes classic models but is her own. This is a very well-considered, “complete” Violetta Valery, dramatically alert and upholding a high musical standard, and the soprano has never looked or sounded more beautiful.

The hostess of Act One is stylish and lightly ironic, masking an edge of concern. We had seen Violetta in the prelude getting a last-minute check-up by Grenvil, whose gestures and mien seemed to say “You’ll be fine for tonight.” Violetta in her gown appears armored for battle, and in a sense she is. She never quite acts as though among trusted friends, and it takes a while for Alfredo to register as more than another guest competing for attention.

The aria and cabaletta have a rhapsodic spontaneity that, of course, is not spontaneity at all—prepared effects are landing with force, but it all seems to be occurring to the soprano in the moment. The repeat in “Sempre libera” is done with a harder tone, as if she is bearing down, willing herself to something. The cabaletta is crowned with a high E-flat that excites the crowd, but sounds to me effortful. This distinguished former Queen of the Night’s vocal center has lowered.

Much later in the performance, concluding the letter reading, Damrau channels some crazy Italian bag-lady soprano, stabbing into “È tardi!” just before we reach the high point of the performance, “Addio del passato,” two verses. There are urgency and vulnerability here surpassing anything in the obvious prior spots—more than in “Dite alla giovine,” “Amami, Alfredo,” or “Alfredo, Alfredo, di questo core.”

Damrau brings her bel canto experience to bear in making the third-act aria something that threatens to become a Mad Scene. Her Violetta is a woman who was prepared even at the beginning of the opera for things to become quite bleak, but she never expected to take this route along the way, to be offered something unexpected and sustaining and then to lose even more.

But after much darting-eyes histrionic display (and singing of precision, elegance, and haunting beauty), she gathers herself and ends the aria on her feet, staring ahead with determination. In all three acts, dramatic understanding and first-rate musical technique combine to evoke a range of moods, and nothing is easy or mawkish. You will sympathize with this Violetta, but even in solitude, she refuses to be pitiable.

Nothing going on around Damrau, alas, is as inspired as she. Jacquot’s production is an essentially traditional one, spare in look, with a few modernistic touches. In staking out a middle ground, it may satisfy no one. Regietheater adherents will find it timid; “What The Composer Intended” types will fling the “E” word over such inconsequential grace notes as a double drag act at Flora’s (male gypsy girls, female toreadors), and those who want pretty pictures will not get enough from the sparse furnishing and moody low lighting. (I have seen the first scene of Act Two staged as if outdoors, but never before in pitch-black night, as here.)

Jacquot is a prolific filmmaker, and his production does not make effective use of stage space. He works around having to direct the chorus much at all. The guests at the first party, men and women alike, are in male period dress including top hats, and they initially appear to us as serried ranks, like the forces ready to follow Nabucco or Manrico into battle. They hold that pose the whole scene, looking on, unsmiling, intimidating. When they return for Flora’s party, now in traditionally gendered dress and domino masks, they remain immobile, posed stiffly on a staircase. In both scenes, anything remotely qualifying as partying is limited to those with solo lines.

Personal direction of the principals is better, and Jacquot probably deserves some credit for Damrau’s detailed work. Much here seems to have been conceived with broadcast/video in mind, such as a divided stage in Act Two, the first scene taking place under a tree at stage right, the staircase for the second scene in view at stage left.The production stirs to life in little moments that read better in close-up than they would have in the theater—the expression of gratitude on Violetta’s face as she eagerly drinks from the glass Annina tilts to her mouth in Act Three; Alfredo, shell-shocked during his father’s aria, dropping Violetta’s letter, which the camera follows as it wafts to the stage floor (simple but lyrical).

It is the sort of production one hopes will come into sharper focus over time, while suspecting the opposite will be the case – it will become duller and more generalized in revivals. There are

few decorative objects, but the people besides Violetta, from the undercharacterized Germonts on down, seem to be decorative objects. Like the dressing table and the beds (a big grand one with a baldachin in the first act, a Manet over the headboard; a sadly diminished sick-ward model in the last), they are there to help her play her scenes.

Francesco Demuro presents a handsome, sweet-natured Alfredo who seems out of his league from the start with this shrewd Violetta. Even more than usual, things seem to be happening to the passive Alfredo; his own point of view does not register strongly. Demuro has sung Alfredo often, including at the Met, but he sounds at the upper limit of what is advisable vocally. I imagine he is a pleasing Nemorino or Fenton. He gets one verse of “O mio rimorsa,” is permitted the optional high note at the end and makes it stick.

His is not a distinctive performance, but it is an idiomatic one with superb enunciation of text, a travel-sized version of what a lot of us miss in such music these days. There is a plaintive Italian throb to some words, for example, “nessuno” in the early “Perché nessuno al mondo v’ama,” which seemingly cannot be taught by giving someone an old Di Stefano recording to study. You have it or you don’t.

Ludovic Tézier’s Giorgio Germont is pleasant to hear but a mild disappointment after his interesting Albert (Werther) for the same director. Tézier has a capacity for superciliousness and other qualities that could have worked in this character, but Jacquot has encouraged (or, in any case, received) only mildness and reserve. It is easy to imagine Demuro’s Alfredo growing older and becoming this Giorgio.

They match up well physically and they are considerate, well-intentioned people. Giorgio bestows a kiss on Violetta’s brow near the end of their big scene, and that gesture gives some idea of the whole conception. The rebuke of Alfredo at Flora’s party seems less rebuke than helpful pointer, and when Giorgio enters in the final scene and sings of his terrible remorse and the serpents gnawing at his breast, one thinks they must be gnawing very gently.

Tézier is, as ever, a patrician singer attentive to finer points, taking care to differentiate in color the three repetitions of “Sì” in “Premiato il sacrifizio,” gracefully shaping “Di provenza” at a slow tempo and making every note clear, limited only by a lack of freedom on top. But the casualness of his delivery and the lack of variation in his affect blur interest in the character.

The comprimari are a good group, but one detail should be mentioned in warning: The Annina, Romanian mezzo Cornelia Oncioiu, has been heavily blacked so that she and Damrau can eventually become the figures in Manet’s Olympia, a painting we see a lot of throughout the opera. If you have seen an Aïda or an Otello darkened this much, you have been going to the opera for much longer than I have. I ascribe no racism to Mr. Jacquot, but I wish he had gone another way with his allusion. The effect is unconvincing and distracting.

Maestro Francesco Ivan Ciampa gets a silken string sound from the Orchestre de l’Opéra national de Paris, and his reading is leisurely, deliberate, and singer-friendly, the sort an admirer calls “loving.” Rhythm is less than taut, and the two preludes advertise tubercular delicacy in a way I find overstated. The performing edition observes several traditional cuts, including the baritone’s cabaletta, several bars of “Gran Dio! morir sì giovane,” and the deathbed party’s reactions to the denouement (the diva gets the last word). What is performed is slow enough to put any saved time back in.

That Jacquot is co-credited for video direction (with Louise Narboni) may alarm survivors of the Decca DVD of his Werther. The filming of Traviata is not so bizarrely fussy. The only significant annoyance is that one camera is stationed center orchestra, several rows back, giving us shaky views from over the shoulder of a female audience member.

One has seen quite enough of her chic bob before the first scene has run its course. Much has been said and written about what is lost when opera is experienced via broadcast or video, but I doubt coverage of the person sitting in front is what anyone has in mind.

With a lesser Violetta, this would be an ordinary, competent Traviata, not competitive with the best available and hardly crying out for dissemination. Damrau’s commanding performance, an old-fashioned star turn on a foundation of intelligence and good taste, makes it worthy of consideration and likely to repeat well.