I’m a long-time fan of the Opera in English series funded by The Peter Moores Foundation that started, fittingly enough, with conductor Reginald Goodall’s performances of Wagner’s Ring cycle recorded live from the London Coliseum and released by EMI. Cast from strength with a team of British singers that included the likes of Rita Hunter, Alberto Remedios, Norman Bailey and Derek Hammond-Stroud. Many of whom never found the kind of recognition they deserved outside of England for one reason or another and it stands alone today as a unique achievement of its era.

Home-grown talent was often used in conjunction with what later became the English National Opera although the connection between the company and the Moores series has always been a bit tenuous. In 1995 Chandos took over the recording duties and the sonics have always been juicy and ample. In fact they were the only engineers I judge who actually captured Jane Eaglen’s voice to advantage—certainly not the group of knob-twisters over at her home label Sony.

The peerless Charles Mackerras made quite a contribution to the discography around the time he was Music Director for the ENO. He conducted a number of early releases including a strikingly elegant La Traviata with Valerie Masterson. He returned to the series in this century and added some of his famous Janacek and Mozart interpretations including a galvanic Makropulos Case with Cheryl Barker. My personal favorite is a positively glowing Eugene Onegin with Thomas Hampson in the title role and Kiri te Kanawa as an unusually impassioned Tatyana. Maybe knowing the words helped?

The discussion about whether we need to know the words is a valid one and I remember Andrew Porter in The New Yorker constantly railing at the ludicrousness of audiences watching performances in languages that they don’t comprehend. Therein opens the Pandora’s Box discussion about adaptation, translation, and transliteration. Up until World War II it was common to have opera, just like theater, performed in the vernacular of its audience.

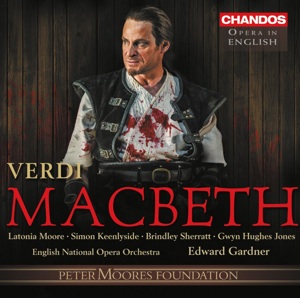

As we’ve become more of an international society, especially in classical performing arts, it’s easier to offer works in their original language. Since funding for the Chandos series from The Peter Moores Foundation has ended I guess it’s only fitting that its last offering was a Shakespeare play written in Elizabethan English then adapted into 19th Century Italian and re-translated back to the English of our modern era. So Macbeth it is.

The excellent liner notes by Mike Ashman remind us that being a Shakespeare fan couldn’t have been easy for Giuseppe Verdi since works of the Bard were inconstantly and inaccurately translated into Italian in his era and even then rarely performed live. Commissioned by Florence’s Teatro della Pergola, Verdi made the specific choice of Macbeth because of the many fantastical elements in its presentation knowing the Florentine audience to have recently relished a case of the spookies from both Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable and Weber’s Die Freschütz.

It was the greatest triumph of Verdi’s career to that point and even then the master went back to work nearly 20 years later for a Paris production and made significant revisions. He replaced Lady Macbeth’s Act II aria “Trionfai” with “La luce langue” and added a witches’ ballet and the duet “Ora di morte” as the Act III finale. Other updates included a complete rewrite of both the chorus opening Act IV “Patria oppressa” and the opera’s final moments banishing Macbeth to an offstage death in favor of a celebratory chorale.

The original 1847 Florence version is very well represented on CD by Opera Rara and the BBC forces, also funded by the Moores Foundation, with Rita Hunter and Peter Glossop and warrants searching out. RIccardo Muti’s recording for EMI originally offered an appendix which included several of the 1847 pieces. Chandos sees fit to give us both endings, and manages to make it fit, while still giving us the opera uncut on two discs with the ballet and all the Paris additions of 1865. Bravo!

Ostensibly this recording lacks rivals since it’s the only one of its kind in English. Yet it’s of such a high quality of execution in singing and orchestral playing that it warrants being numbered among the best in the current discography. That’s preeminently because of the leadership of Conductor Edward Gardner who is the current music director of the ENO. Using the home orchestra (but a studio pickup chorus of considerable size) he revels in Verdi’s youthful tempi instead of apologizing for them by rushing past them like others do.

Taken in its context Verdi’s score was uncommonly violent for its time and, apropos the subject matter, its orchestrations decidedly creepy. Our 20th century ears tend to hear the monkey-grinder tempos dominate all else but the macabre is there. Gardner gives a gloriously tight reading of the prelude and is especially persuasive both in the scenes with the witches and in the final pages of the Banquet scene at the Act II finale where he does a double-clutch ritard on the climaxes. He’s also magnificent with the Ballet which is a rare and beautiful thing and gets every little bit of juice out of the trumpet fugue finale of the Paris version as it builds to the Ultimo. The apparition scene always goes on for far too long but that’s not his fault.

Simon Keenlyside is already well represented as Macbeth in Italian from Covent Garden on video. He’s not a Verdi baritone by birthright but does manage to parse his lyric instrument adequately to the task at hand. At this stage in the career he knows more than anyone his own limitations and strengths. He’s excellent in pointing the English text and is wonderfully varied in dynamic which includes a prickling parlando in the “dagger” aria.

I do disagree with the very occasional use of an unattractive straight tone which I feel robs the listener’s concentration from the lyrics and him of his communication. He does do a restrained, evil chuckle during his conversation with Lady M. about murdering Banquo’s family which I enjoyed immensely. His voice is still uncommonly beautiful at times, especially factoring his age into the equation, and his hushed lead-in to the banquet scene is equal parts of malevolence and refinement.

Brindley Sherratt has been singing with both ENO and the Royal Opera for quite some time and I’m sorry that this is my first notice of him. Its a pitch-black Bass sound with perpetual legato and he’s not only excellent in his aria “Come dal ciel precipita” (here; ”Black is the night”) but he’s also got an infectious case of the oogie-boogies in the first scene on the Heath with the WItches and Macbeth. It actually made me sorry he didn’t last past Act II.

Now it’s no news to anyone reading this that we live in an imperfect world and if there’s been one ubiquitous chink in the Opera in English series armor it’s been their tenors. I don’t even really think they’re completely to blame because of the pervasive English vocal school of clear-white, nymphs and shepherds, tone. Also singing early Verdi in English makes nearly all tenors sound like Nanki-Poo wandered in accidentally from the D’Oyly Carte. Sadly Gwyn Hughes Jones as Macduff proves no exception. He’s perfectly adequate, mind you, but in a role where record companies make a point of outdoing themselves with the likes of Luciano, Plácido and José, he’s reedy when we want robusto. When’s he joined by the Malcolm of Ben Johnson in the final scene I was hoping for a little blood in the voice but they’re both gradually and gratefully overwhelmed by the chorus and I’ll leave them there.

Meanwhile estate services at Castle Macbeth are being overseen by our Lady, American soprano Latonia Moore. Let me assure you now that we’re in very capable hands…as long as you lock your door before you go to sleep. I think this may be the first time I’ve ever heard a truly beautiful voice sing this role. There have certainly been many great singers who’ve brought their gifts to this part but Ms. Moore has a caliber of tone that is among the rarest.

She doesn’t sound harsh and driven like some of the mezzos who’ve laid claim. She’s also wickedly luscious and even in scale and unforced and substantial below the staff. Fearlessly dispatching with ease and grace the host of vocal hurdles the composer puts before her. She flaunts an un-faked trill in the Brindisi when she gets a moment to set it up and is ferocious in the climax of “La luce langue.”

The voice is never tight or strident on the top and it’s such a pleasure to be able to relax and listen to someone “play” with this role and not have to brace yourself for the next disappointment in a performance flush with vocal compromises.

Ms. Moore proves herself perfectly capable of dominating a Verdi ensemble and if she needs to break a word on the rare occasion because of an occasionaly awkward English translation I forgive her…completely. The Act I duet “Fatal mi donna” (here: “Did you not hear it…?”) is particularly persuasive, with Mr. Keenlyside hushed and horrible and Ms. Moore by equal parts feminine and stern, yet always fleet in her ornaments

That femininity in her tone and throughout her performance may be the thing that makes it so unique since the majority of operatic Lady Macbeth’s have proven to be little more than steam-rollers in spanx. She caps it all with a riveting sleepwalking scene although she admittedly does indulge in a bit of a gear shitfor the D-flat in the final phrase. Her sung English is also strikingly beautiful and another thing to savor in her portrayal.

I also have to single out the 60 members of the ad-hoc Opera in English Chorus who do a superlative job and the ladies most especially for their crisp contribution to the scenes with the Witches and their most excellent and mostly understandably diction.

Recording in the Blackheath Halls, which is apparently the oldest surviving concert venue in London, the Chandos engineers do their always superlative job of capturing the music and voices with scope and clarity. Special praise to whomever provided the stunning thunder effects on the heath that made the floor of my living room rumble.

So a very sad farewell to the Opera in English series with this it’s 62nd release but one well worth adding to your collection for the many, many, pleasures it affords.