Les Troyens is one of those things, or often two of those things, that should be a big event or it practically needn’t happen at all.*

The keynote is grandiosity in the best way, from the subject to the musical demands (let’s include the implicit challenge of one singer performing both Cassandre and Didon—not because it happens often, but because it’s hard not to think about it simply on account of its ever having happened.)

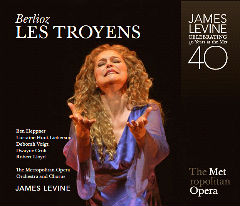

In 2004 the Met mounted a new production of Troyens and indeed it was an event, not least because of the participation of Lorraine Hunt-Lieberson. It’s hard, now, not to think of this as a grand farewell, though it simply wasn’t. LHL was scheduled to sing in Mark Morris’ resoundingly banal Orfeo a few years later, and might have saved it from itself. In any case, only those close to the artist may have known that chances were good that her farewell to Troy might have a terrible extra meaning.

LHL was, onstage, the spiritual anchor of the piece, and perhaps more so on record she’s the reason it still feels like an event. Among the principals, she’s the only one who wholly belongs in the role she’s been cast in.**

Listening, we can savor (or if you weren’t there, I can taunt you most unsympathetically with) the memory of how she only amplified the tragedy in the singing of the great farewell with an instinctive physicality that found the midpoint between nobility and utter defeat.

On record what I notice is how often she opts for understatement: the phrase “éternelle nuit” is not, école de Verrett, chested out, not a Bernhardt gesture; more of a sigh than a moan. I tend to think it’s bullshit when singers go on about trusting the music—everyone interprets—but there is a certain sense here of disengaging the actorly devices of deliberate pathos.

Others acquit themselves honorably but with mixed results. It was immediately clear onstage that Cassandre was one of those roles that had no reason to be less than a success for Deborah Voigt but was going to be anyway. Her French is fine, overenunciated if anything, and she’s in lustrous voice, but she doesn’t always connect with Cassandre and it doesn’t add up to much of an emotional listen though there’s certainly aural pleasure in it.

Ben Heppner’s Énée is one moment heroic, the next downright pedestrian. He doesn’t crack, but it seems to cost him a lot at times. I suppose he had sung the role before, but you might be forgiven for wondering. Some lyrical moments are quite stylish; others (“Nuit d’ivresse”) lacking in elegance. It isn’t amateurish but it isn’t complete. Dramatic parts of this admittedly murderous sing either knock it out of the park (as near the end of the Siege of Troy) or falter disappointingly. Missing C aside and forgiven, “Inutiles regrets” is marked by what sounds like nerves.

Heppner has always been a variable singer at the Met, though usually by the performance—you can tell a little while in if you’re getting good or not-so-good Heppner. He’ll always have work, because he fills a mostly empty niche in the roster, and because at his best he’s glorious. Énée is neither the triumph of Tristan on a night when it’s working nor the agony of an Otello on a night when it isn’t.

Smaller roles are similarly uneven. Matthew Polenzani delivers possibly the finest singing, per se, on the set in Iopas’ air, fearless and stylistically right. (The text of this aria, loosely translated: “why do I get such sloppy seconds in Met casting when I sing better than basically anyone else they hire?” You may have read different, but this is what it means.)

Gregory Turay, who briefly looked like he might have a bigger Met career, I remembered as quietly affecting, but credit may go to Francesa Zambello there for her striking staging of Hylas’ affecting little scene; on record, he comes off as a little too droopy in an aria with a high risk of that. And really, what were they doing putting Elena Zaremba in everything those few seasons? Yeesh.

It’s tough to write about the Met Orchestra under James Levine because it’s usually pretty much a cut and paste job. Accolades begin to look alike, and this is no exception. In terms of pacing, style, singer-responsiveness, there’s little room for betterment that I can hear. I will say that in some music the excellence of Levine is a passive thing, sometimes to the point of sounding too tasteful. Here it is an active participant.

*Oh hi. I just wanted to make sure it was clear that this is not the same as saying “nobody can sing Les Troyens these days so why don’t we just shelve it for fifty years.” I hate that shit. All I’m saying is, if you’re going to do it, don’t do it hemipygously.

**Ok yes. It is a tiny bit stretchy at the top during her entrance, but this is the nittiest nit that ever nat and I dismiss it.