It’s no easy easy task to “re-review” one of the most discussed and scrutinized opera productions of the last few years. Mary Zimmerman’s mise-en-scène of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor has been extensively examined since it was chosen to inaugurate the 2007/08 season of the Metropolitan Opera, provoking very mixed reactions both from the professional critics and the audience. Some saw it as a compelling and original production, while others viewed it as an abysmal failure.

So much has been written about this Lucia, especially in light of the fact that in these past two years it has starred a group of extremely high-profile sopranos. In addition to Natalie Dessay, the “original” Lucia, two other superstars, Diana Damrau and Anna Netrebko, have appeared in it, prompting the press to attend the production again. A fourth, Annick Massis, albeit a highly respected artist, apparently lacked the diva status to drag the reviewers back to the opera house en masse.

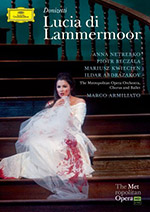

But the Met’s Lucia requires a second look if only because it has just been released on DVD by Deutsche Grammophon with Netrebko in the title role.

Let us begin with the production itself. Sir Walter Scott’s The Bride of Lammermoor, which provided the inspiration for Salvatore Cammarano’s libretto, sets the action in Scotland during the reign of Queen Anne (early 18th century);

Ms. Zimmerman has transposed the action to the Victorian age. Some have suggested that her reason for this update was to highlight the incipient collapse of the British empire through the depiction of the shattering of a woman’s mind, her family and a whole social system. Others have theorzied that the producer’s main intention was to recreate a true Gothic story, and that particular historical period, with its penchant for ghosts, was the ideal background. Yet others implied that the revision was simply a gimmick to introduce into the story novel elements like the photographer or the hypodermic needle used to sedate Lucia.

Personally, I enjoyed the production and didn’t find many faults.

It is true that the change in epoch makes the story historically problematic (why would Edgardo have to flee to France?), but again, this doesn’t seem to be an element of concern for modern directors: consider the plethora of Toscas taking place in Fascist Italy, where the characters are still distressed about Napoleon’s victory at Marengo or the fall of the Roman republic.

I was not bothered by the presence of the photographer who, during the glorious sextet, frets about the stage gathering Lucia’s family members to take their picture and flashing his camera immediately after the last note of the music. It is probably true that this device was introduced because of the producer’s basic lack of trust and faith in what she must consider the epitome of artificiality, the concertato, where the action stops for several minutes. Yet, I didn’t find it obtrusive.

The appearance of ghosts has also been widely excoriated, but I found them to be an integral part of Ms. Zimmerman’s conception of the opera as a Gothic story. As the director herself comments in the DVD special features, “the ghosts are absolutely real in the Scott novel. He describes them and the readers see them. Even when the other characters aren’t there, they are described. … For me the ghosts are sort of a spirit of revenge that haunts the ground at Ravenswood and reaches through Lucia to get Edgardo”.

The tangible quality of the ghost in the Act One fountain scene is of vital importance for Ms. Zimmerman’s view that Lucia is sane at the beginning of the opera, her descent into insanity being a gradual process. Personally I am inclined to think that Donizetti’s music is suggestive of Lucia’s precarious state of mind from the start, but I am open to Ms. Zimmerman’s theory, because it is coherently developed.

There were a few ideas that didn’t quite work, the worst being the cutting of the murder to about half a minute by showing Lucia and her “sposino” going upstairs at the beginning of the third act.

The look of the production is fantastic (and I use this terms in both its meanings: exquisite and fairy-like) and it is clear that special attention was devoted to the singers’ acting. And yet, as is often the case when a controversial production is later revived, some of the most daring details have been excluded or toned down.

In the initial run, during the Larghetto “Ardon gl’incensi,” Natalie Dessay’s Lucia slowly removed her gloves and on the words “ogni piacer più grato” while lying on her back, she caressed her body in a provocative manner, imagining her wedding night with Edgardo. In this revival Ms. Netrebko does nothing of the sort. Whether this omission was due to the director’s second thoughts, or to the new diva’s insistence, we will never know.

Netrebko, the raison d’être of the DVD, was scheduled to appear in this Lucia earlier in the season, but had to cancel because of the birth of her first child. Here, despite some lingering signs of puffiness, the Russian soprano looks beautiful and glamorous. Her timbre is dark (my personal description is “melted chocolate”), rich and supple, agreeable and captivating. It is in a few words what is commonly called “a beautiful voice.” She knows how to sing “sul fiato”, floating the sound, and is able to modulate the tone. Her voice is evenly produced through virtually the entire extension, with no conspicuous gear shifts between registers.

“Regnava nel silenzio” was admirable for its expressiveness and use of legatos and pianos. Trills and mordents, on the other hands, seem not to be her forte, as she disregarded all of them. The rendition of the cabaletta, performed without the traditional higher variations, was nonetheless stirring.

Ms. Netrebko has a strong command of the demands of most of the role. The first act duet with the tenor, the second act duet with the baritone and the wedding scene are outstanding; it is clearly music where she can leave her mark. However, her singing is by no means flawless, as we hear when she faces the crucial test for any Lucia: the Mad Scene. Nothing she did was vocally embarrassing, yet there is no denying that her passagework was often less than tidy (let’s say even a bit sloppy) and her extreme high notes sounded fatigued. The famous flute cadenza (which, as everyone knows, Donizetti did not write) was undoubtedly the least impressive moment of Ms. Netrebko’s performance. She ducked the first E flat, and the final one turned out shrill and short.

Once more, no trills were to be heard, and in the cadenza this was particularly conspicuous because the flute trills and she did not. Ms. Netrebko could of course sing an entirely different cadenza, more suitable to her current vocal gifts, but audiences are used to the traditional one and often react with indifference (to say the least) when it is not performed. It is regrettable that a cadenza Donizetti never wrote has come to be considered the centerpiece of the opera, and a litmus test for any soprano who wishes to sing this work.

As a matter of fact, Donizetti’s original version of this opera, with its slightly higher keys, would be much more congenial to Ms. Netrebko’s voice. These are the composer’s keys and the ones traditionally used in performance, respectively: “Regnava nel silenzio” ( E flat/D); “Quando rapita in estasi” (A flat/G); “Il pallor funesto, orrendo” (A/G); Mad Scene (F/E flat). Obviously, of course, when performing the Mad Scene in the original key, very few sopranos can end with the cadential high note of F.

As I said, I personally chose to close one eye over her imperfections as a virtuosa, not least because Ms. Netrebko is a consummate actress. She instinctively finds the pertinent movement, the appropriate glance for every moment of the opera. Many are the details that caught my attention, such as the sarcastic shoulder shrug she gives her brother in the second act duet when he tells her “tuo fratello sono ancor”.

She draws you into Lucia’s drama and makes you believe in it. She is, in other words, a charismatic artist. Dumas père, speaking of Fanny Tacchinardi Persiani (the creator of the role of Lucia) and her apparent lack of intensity on stage, quipped: “She is a brunette who sings like a blonde.” Anna Netrebko, though, is a brunette who sings like a brunette!

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEMEaXLcRQA

Judging by this performance (as well as by other recent appearances in bel canto roles), it seems Ms. Netrebko’s career would be better served by steering towards a more lyric, less virtuoso repertoire — especially roles where the high E flat is not considered essential.

This run of Lucia di Lammermoor performances and the taping of the DVD were supposed to reunite Netrebko with Rolando Villazon, but the “dream team” turned into a nightmare when the tenor’s voice spectacularly failed him in the first performance, cracking on the climax of the second act confrontation scene.

Piotr Beczala came to the rescue. The Polish tenor has an exquisite, full-bodied Italianate voice, with hints of that “sob” (“lacrima nella voce” is a better description of this quality) which makes a singer particularly endearing if used intelligently. It took him some time to warm up, and he yielded his best work in the final scene. Early in the opera some of his Bs flat showed a touch of metallic sound and impurity, but the B natural in the cadenza of “Fra poco a me ricovero” was splendid. “Tu che a Dio spiegasti l’ali” was moving and affecting. He actually managed to sound moribund without resorting to stifled yells.

His roughest moment, relatively speaking, was the Wolf’s Craig scene, where his top sounded at times perilously taxed by the high tessitura in such an intense, dramatic context.

Baritone Marius Kwiecen’s Enrico was less of a villain than he is generally portrayed, and rightly so: after all, this character is not an evil person; he is just a desperate man who is well aware that his (and his family’s) fortune and even his life depend on Lucia’s marriage. Mr. Kwiecen’s has a mid-sized, velvety voice; he is most of all capable of depicting Enrico’s rage without huffing and puffing and artificially enlarging the sound.

Russian bass Ildar Abdrazakov was almost wasted in the role of Raimondo, but grabbed every opportunity to show off his first-class talent. He can certainly be forgiven for holding the last note at the end of “Dalle stanze, ove Lucia” for what seemed an eternity , even though Donizetti requires the bass to stop with the chorus.

Marco Armiliato is a brilliant conductor. The sound he elicits from the orchestra is incisive, crisp, neat and attentive to each detail; he wraps the opera with an appropriate mysterious Romantic aura. Unfortunately he and the Metropolitan Opera don’t seem so respectful of the score from a philological point of view. Some of the daccapos are eliminated, and when they are present, they lack interesting variations. Most of the traditional internal cuts are still executed, including the whole second part of the act two finale “Esci, fuggi.” I firmly believe that nowadays, after decades of bel canto renaissance, a major opera house should perform the opera in its entirety and with variations in the daccapos, more so if the performance is to be recorded and commercially released.

One element that I particularly cherished was the use of the glass harmonica during the Mad Scene; as it is well known, Donizetti’s original intention was to employ this exotic instrument, which gives the scene an eerie, supernatural atmosphere.

Having heard this cast live in the opera house, I can attest to the high quality of the sound of this recording, which gives a very accurate idea of the actual size of the singers’ voices. I was also impressed at how sharply the various sections of the orchestra can be heard.

The DVD is exquisitely directed by Gary Halvorson. He is a Julliard trained pianist and, as with his other recent Met high-definition theater simulcasts, he knows quite well whom and what to capture. There are very few incongruities between the music and what is shown on film. The alternation between close-ups, mid shots and master shots is well balanced.

On the other hand, I am not fond of his occasional choice of filming the singers as they leave the stage while the music is still playing. This, together with his showing them in the wings (documentary style) at the end of the first act, disrupts the atmosphere. I believe this type of behind the scene action is best reserved for the DVD’s extras section, which features Natalie Dessay briefly interviewing cast and crew.