In part 3 of this story, I will explore the ends to which the Arts Council exercises this power and the institutional ideology that led to sweeping funding cuts to the classical music sector on November 4.

Arts Council England’s sweeping cuts to the classical music industry have their origin in its 2020-2030 ten-year plan, titled “Let’s Create.” For the next ten years, the Arts Council is going to be taking a more “place-based” approach to arts funding: the goal is to bring art to “more people in more places” by “leveling up” cultural investment in areas outside of London.

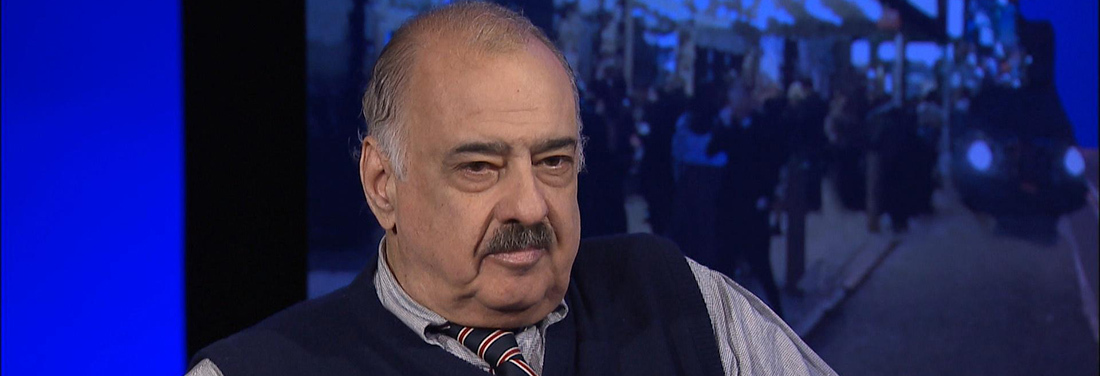

Claire Mera-Nelson, the Arts Council’s director of music, framed this shift in terms of equity: “the phrase that our CEO uses is that ‘talent is everywhere but opportunity is not’ […] So, we really wanted to take that charge on and think about how we could make a more equitable spread of opportunity across England.” She notes that the majority of the Arts Council’s investment has previously been in the London area, leading to a “critical mass of artists” in the capital.

The Arts Council’s 10-year “place-based” strategy was given new urgency when Nadine Dorries, then the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, ordered the Arts Council to increase its investment outside of London via a 2022 government white paper. (Dorries, it should be noted, was condemned for her performance in this role by the House Committee on Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport after repeatedly misleading her fellow MPs.)

Boris Johnson, then the Prime Minister, argued that this white paper was not about “cutting down the tall poppies, or attempting to hobble the areas that are doing well” but about “closing the productivity gap” between London and the regions to promote “more growth, more jobs, and higher wages right across the UK.”

The “Leveling Up” white paper promised that “100% of the additional funding for Arts Council England agreed at spending review 2021” would go to organizations outside of London.

However, Dorries later clarified (via a Funding Settlement Letter to the Arts Council) that an increase in arts provision outside of London would be partially achieved by slashing funding to London arts organizations. She ordered to the Arts Council to reduce its investment in the capital by £24 million per annum and warned that “the largest nationally and internationally renowned cultural organizations” would be expected to increase their activity in underserved regions by 15% by 2026.

Johnson and Dorries’s “Leveling Up” agenda was widely condemned by arts practitioners. One NPO CEO penned an anonymous letter in the Arts Professional complaining that the government “seem determined to use the financial levers at your disposal not to support what we do, but to punish us for the structural problems that all governments, but Conservative governments particularly, have failed to address.”

Some noted the complex precedent that the government’s “Leveling Up” agenda set for the already storied relationship between the Arts Council and the government. The Cultural Learning Alliance suggested that “the strong, detailed directives in this letter indicate that the arm’s length has been significantly shortened.”

And so, a perfect storm emerged: a funding body that believes that funding to large, London-based arts organizations is inherently inequitable found themselves “in bed” with a disgraced right-wing government who hoped to artificially boost economic prosperity in the regions by imposing austerity on arts organizations in the capital.

And all of this was enabled by the murky relationship between the Arts Council and the government, in which the ambiguities of the arm’s-length arrangement are used to obscure the individual ideological motifs of ministers and bureaucrats.

So, CEO Darren Henley’s remarks that the latest round of Arts Council funding is “fairer in its distribution” than ever before obscure two underlying assumptions: 1) that lack of arts funding in the regions is a result of arts organizations in London having received too much funding in the past, and 2) that the best way to fix this is to systematically dismantle arts funding in London.

What the Arts Council doesn’t acknowledge in its implementation of the “Leveling Up” agenda is that public arts funding fell by 35% in Britain in the ten years following the 2008 financial crisis and corporate sponsorship of the arts in Britain fell by 39% between 2013 and 2018 (according to a study by the National Campaign for the Arts).

Therefore, the central reason why arts organizations outside of London are underserved by public subsidy is that arts funding, on the whole, has failed to increase to meet England’s demographic needs.

According to the Office of National Statistics, the UK’s population rose by over 3% between 2014 and 2019. Most of this growth was concentrated in London: The City of London saw a 58% population increase, while Camden, Tower Hamlets, and Westminster witnessed population increases of around 14%. But there was also significant growth outside of London: Tewkesbury saw its population increase by 10.7%; Coventry experienced a 10.6% population boost; Manchester grew by 6.6% and Salford by 7.2%; in fact, only 24 local authorities across the UK experienced population decreases during this period.

All this population growth took place as per-head arts funding was consistently shrinking. Therefore, moving arts funding outside of London may temporarily increase cultural activities in certain underserved areas, but it won’t address the overriding problem: that arts funding across regions of the UK is not fit for purpose and has not increased to meet the needs of audiences and artists alike.

The “Let’s Create” and “Leveling Up” agendas have been created to mask this fundamental failing—to create the appearance of more equitable arts funding as the entire system slowly collapses. It is the definition of virtue signaling: the Arts Council and the Department of Culture, Media and Sport can pat themselves on the back for their magnanimity while refusing to address the systemic problems that they themselves created.

If the Arts Council was truly committed to equity and diversity, it would work with government to increase the overall funding available to arts organizations: this way, it could support a vibrant portfolio of regional arts organizations without stifling the diversity and equity efforts of existing organizations. It would create new funds to encourage diverse creatives, to bolster smaller and emerging companies, and to create new regional opportunities for arts engagement while continuing to underwrite the outreach efforts of larger, metropolitan organizations.

It really is simple: You cannot promote equality in the arts by cutting arts funding. And you certainly cannot do it by simply shuffling existing funding around: this simply undermines the kind of consistent financial support required to make the real, long-term organizational changes necessary to promoting accessibility and inclusion.

And the effects of the “Leveling Up” agenda have been devastating. The Arts Council explicitly cited this agenda in its decision to defund organizations like the ENO and reduce funding to other large London-based arts organizations like the Royal Opera House, the London Symphony, and the London Sinfonietta.

But will the latest round of Arts Council England funding actually achieve its stated aims?

One can see the blunt logic for defunding the ENO: there’s already an opera company in London, what’s the point in having two?

As a consolation prize, Arts Council England has offered ENO £17 million over the next three years to relocate to Manchester—part of their “Leveling Up” program designed to boot arts organizations out of London. The ENO have indicated that they will try to continue to manage the London Coliseum as a commercial venue as they seek a new location with these relocation funds.

Mera-Nelson suggests that the Arts Council decided that the ENO should move outside of London precisely because of its good track record for artistic innovation:

There are people in that organization who have shown exceptional vision. And we think that if we tasked them with this challenge, that ENO, with its history of engagement and prioritizing the needs of England’s audiences and prioritizing the development of English artists and creatives, can make this change.

She even cites ENO’s artistic director, Annilese Miskimmon, one of the most pioneering women leaders in the arts industry.

But the question remains: is £17 million really enough money to relocate an entire opera company of the ENO’s size over three years? I’m doubtful. Most of that money would surely go into purchasing or renting a performance space, rehearsal space, storage space, and office space in Manchester (for reference, Opera North just refurbished its premises in nearby Leeds to the tune of £18 million—ENO will be starting from scratch.)

That would leave almost no money for staff retention. What would happen to the orchestra, the chorus, the education staff, the costume designers, the marketers, the fundraisers, and all the other personnel who currently work for the company?

It seems that a move to Manchester on just £17 million would essentially mark the end of the ENO as we know it and would not be the boon for the regions that the Arts Council are marketing it as. The Arts Council are sending the ENO to Manchester as a gutted shell of an opera company and then congratulating themselves on their regional arts provision.

Besides, Opera North already tours its entire mainstage season to Salford (which is in the Greater Manchester region): If the goal is bringing opera to regions that don’t have access to it, Manchester is an odd choice.

It is also telling that, out of both major opera companies in London, the Arts Council chose to relocate the ENO, generally the cheaper and more accessible of the companies. ENO gives out free tickets to everyone under 21 and its cheapest tickets are just £10. 1 in 7 ENO attendees are under 35 and 50% of its audience are coming to the opera for the first time.

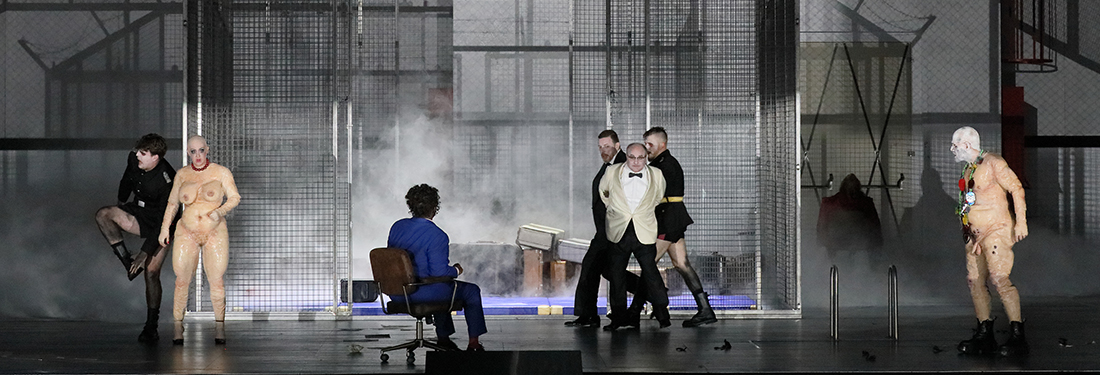

Indeed, after a few rocky years, the ENO has been experiencing something of a renaissance recently, with a series of critical and popular hits, including its acclaimed production of Birtwistle’s The Mask of Orpheus and, of course, Glass’s Akhnaten, a co-production with the Metropolitan Opera.

And, in a great twist of irony, over 50% of ENO’s audience already comes from outside of London.

If the Arts Council was really concerned with fairness and providing to audiences outside of London, why on earth did they go after the ENO, an opera company that was already making key inroads towards these goals?

It seems to me that the Arts Council went after the ENO in part because it was an easier target. It’s less prestigious than the Royal Opera House. It already has an historically tempestuous relationship with the Arts Council: the Council has temporarily rescinded ENO’s funding in the past with little resistance. And financially compelling the ENO to move to Manchester would very easily fulfil the quotas set out by the “Leveling Up” agenda.

Indeed, for all the talk of “fairness,” one can’t help but wonder whether convenience and snobbery played a role in the decision to defund the ENO.

And for a funding body that is purportedly trying to increase funding outside of London, the Arts Council certainly cut a considerable amount of money from arts organizations based outside of the capital.

Think of the Psappha ensemble—a world-class new music ensemble based in Manchester and once the favored ensemble of Peter Maxwell Davis, responsible for over 30 years of world premieres (outside of London, too). Cutting its funding is entirely antithetical to the Arts Council’s purported aims.

Or think of Welsh National Opera, who now has to completely reimagine their operating budget now that their funding has been cut by over a third for three straight years. WNO tours not only Wales, but also various regional centers in England, including Oxford, Birmingham, Liverpool, Bristol, Southampton, Plymouth, and Milton Keynes. They are a major regional provider who the Arts Council England has decimated against their own political logic. (WNO has already announced that it will no longer tour to Liverpool as a direct result of the Arts Council funds—so much for supporting the arts outside of London).

Or think of Glyndebourne: Their Arts Council funding doesn’t support the festival itself, but rather their touring and education efforts (Glyndebourne tours its festival offerings to Milton Keynes, Canterbury, Norwich and Liverpool). It is difficult to see how those tour offerings can continue now that their funding has been sliced in half.

If I was an opera lover in Milton Keynes, for example, I would look at the latest Arts Council funding announcement and feel totally neglected: no funding for Welsh National Opera to tour, no money for Glyndebourne to tour, and if I wanted to take the train to London to see an opera, I can’t get a cheap ticket to the ENO anymore. So much for funding arts in the regions.

Thus, even a quick examination of the Arts Council’s funding choices reveals how empty their rhetoric of funding arts outside of London really is. It’s a simple divide and conquer strategy. The Arts Council pits the capital and the regions against each other as the entire pot of arts funding gradually decreases.

But what is most worrying to me is the paternalism of the Arts Council’s approach.

According to historian Anna Upchurch, John Maynard Keynes established the Arts Council with the explicit goal of promoting independence for artists, to afford them a degree of creative freedom that the ministerial model wouldn’t allow. Keynes, she argues, was “unequivocal in his desire to establish a flexible organization not staffed by career bureaucrats.” Indeed, Kenneth Clark, one of the Arts Council movement’s founding members, explicitly decried “binding all creative activity with the chilly tentacles of the Civil Service.”

The Arts Council today stands in direct antithesis to this vision. It uses the threat of financial reprisal to force specific aesthetic directives onto arts organizations. It explicitly the artistic agendas of the organizations that it funds. It is not only highly bureaucratic, but this bureaucracy can be inflexible and even obstructive to those who do not comply with those agendas.

Indeed, the recent round of funding decisions suggest that we have entered a new era in the Arts Council movement: in which arts organizations face the constant threat that a small group of bureaucrats may unilaterally order them to change their artistic remit and move cities at a moment’s notice.

So why does this matter at an international level?

England, as a colonial power, still holds major sway over arts policy around the globe – and particularly in the Commonwealth. The very fact that somewhere like New Zealand still has an arm’s-length funding body virtually identical in style to Arts Council England demonstrates the soft power that England holds over cultural politics in its former empire.

Arts Council England’s decisions will have profound knock-on effects around the globe. And these effects will be particularly devastating in places like Australia and New Zealand, where colonial policies long scuppered any meaningful national arts strategy.

Needless to say, arts organizations around the world who receive public funding through arm’s-length organizations should heed carefully what is happening in England and prepare for the worst.

Arts Council England, as a global policy trendsetter, may have sounded the death knell for the international opera industry as we know it.

Comments