I’m treating this overview as a comprehensive formal introduction, one of the most passionate “case-pleadings” I’ve ever had the pleasure of doing. For this, I’ll be like that “agent with one client.”

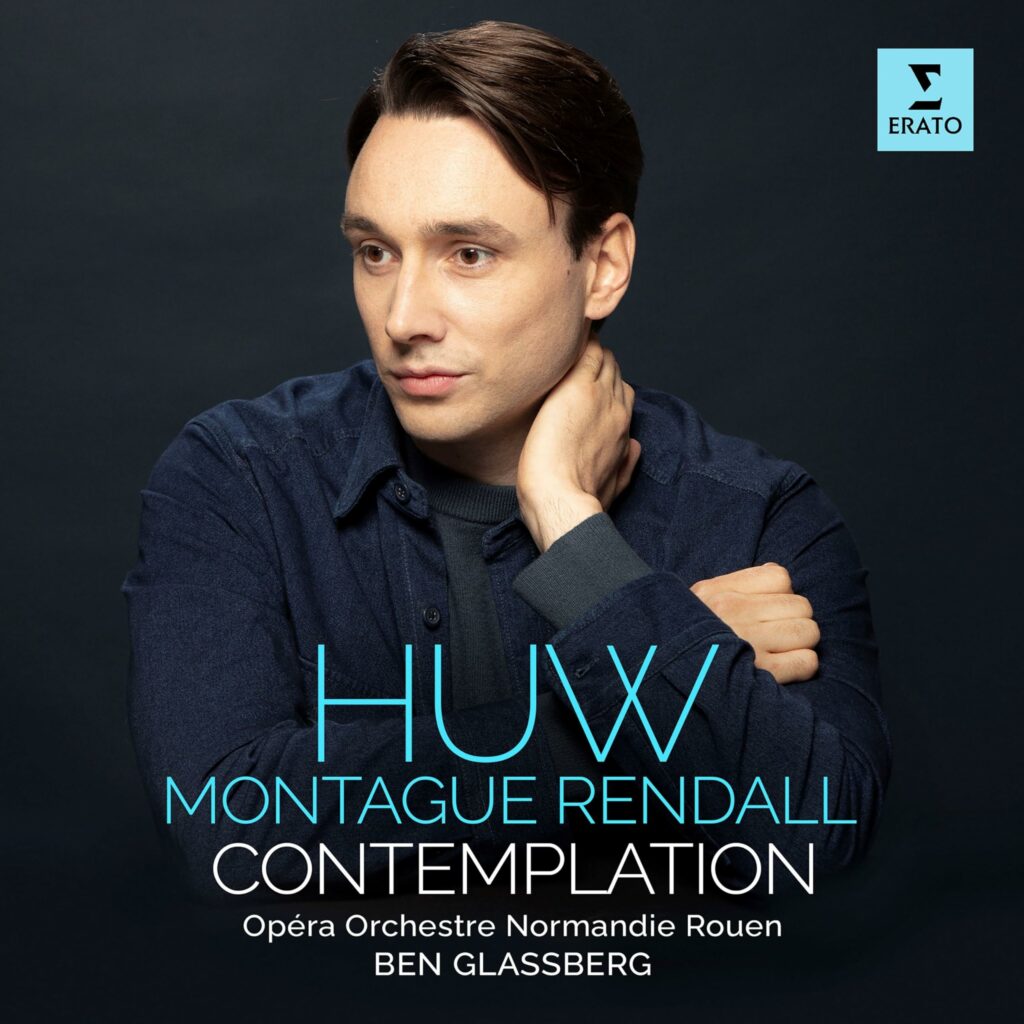

It’s not often that I feel enthusiastically emboldened to declare that this is one of the very greatest recital discs I have ever heard. And a debut recital disc at that. Baritone Huw Montague Rendall is one of the most obscenely talented artists I’ve ever been privileged to hear.

Behold the widely varying, dazzling program:

Thomas: Hamlet,”J’ai pu frapper le misérable” “Être ou ne pas être” (Hamlet)

Gounod: Faust, “Ô sainte médaille” “Avant de quitter ces lieux” (Valentin)

Korngold: Die tote Stadt, “Mein Sehnen, mein Wähnen” (Fritz)

Mahler: Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen: No. 1, Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht

Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen: No. 2, Ging heut’ morgen über’s Feld

Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen: No. 3, Ich hab’ ein glühend Messer

Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen: No. 4, Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz

Britten: Billy Budd, “Look Through the Port” (Billy)

Gounod: Roméo et Juliette, “Mab, la reine des mensonges” (Mercutio)

Duparc: Chanson triste

Mozart: Le nozze di Figaro, “Hai già vinta la causa” (Almaviva)

Mozart: Don Giovanni, “Deh vieni alla finestra” (Don Giovanni)

Messager: Monsieur Beaucaire, Chanson de la rose rouge. “Au jardin où les fleurs sont écloses” (Beaucaire)

Mozart: Die Zauberflöte, “Papagena! Weibchen! Täubchen!” (Papageno, Die drei Knaben)

Mozart: Die Zauberflöte, “Pa-Pa-Pa-Papagena” (Papageno, Papagena)

Rodgers: Carousel, “Soliloquy” (Billy)

Mahler: 5 Rückert-Lieder: No. 3, “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen”

You know what my problem was in the contemplation (ok, ok, obvious wink wink) of reviewing this recital? How to even begin doing justice to this magisterial talent’s work here, a dizzyingly prodigious testament as such if ever there was one.

So, in lieu of my usual prolix fashion, I will urge one and all to simply buy this CD and let Montague Rendall do his own good “justice” to and of himself, touching upon further down, my own favorites.

Really – it’s an absolute essential of what a complete art and artistry entails in its dedication, devotion, and commitment to the ultimate meaning of those terms. There is not one selection here that has anything of the perfunctory to it, the “just-learned” aspect; no matter the language, genre, or style of composition, everything is invested and mastered with the kind of commitment only a true, consecrating artist worth his salt has the capability of achieving.

Turns out, Montague Rendall chose each one of these pieces con intenzione; in the extraordinary, deeply thoughtful essay he wrote himself in the accompanying booklet, he offers the basis of his choices:

“Music has continuously emerged as a commanding force in my life, offering guidance amidst the tempestuous torrents of existence. It has been an invaluable companion, offering profound insights into the labyrinthine complexity of the human psyche. The meticulously chosen compositions have served as mirrors, reflecting the multifaceted realities of life and stimulating introspective journeys into the depths of my consciousness.”

This recital being a major artistic event, the heralding-in of a major musical force in our midst, I have one reservation concerning this release: the booklet is insufficient in that it offers no biography of Montague Rendall, nothing about his training, career, repertoire, and background – for example, that his parents are the esteemed artists mezzo-soprano Diana Montague and tenor David Rendall. His website provides all this. There’s nothing either about the recital’s formidable and thoroughly collaborative conductor, Ben Glassberg, which again you have to do via a Google search. Secondly, though the booklet provides the sung texts for each piece, it does not provide translations, instead directing you to the Warner Classics webpage to obtain them.

I found doing this to be inconvenient, and the cost-saving measure unfair, I think. The only way I could make this akin to the time-honored way of listening was to print out the booklet, some 25 pages. For those who buy the album via a download this is the only option of course, but the hard copy I feel should, for this enterprise, have merited a deluxe box with a full bio, texts and translations to signify the propitious importance of this star-making release.

Us seasoned opera aficionados all know the thrill of discovering an emerging, exciting new artist, and no less with Montague Rendall, I wanted to know and hear more, and the advent of YouTube happily presents those multiple opportunities. In this case, I wanted to know more about the person behind this scholarly, musically impeccable artist. This half-hour mutual interview with the soprano Ying Fang is absolutely charming, and revealing of a humble, sincere man, anything but self-preening and puffed-up in his own self-importance, and devoted to his calling:

I do want to commit, though, to citing my favorite pieces here. The majority of the whole, though, contain some of the best performances I have heard in a long, long time, of golden-age caliber.

The Count’s scene from Figaro is absolutely hair-raising, alert, rhythmically propulsive, organic in its wedding of text and music, fierce but not Teutonically blustering, the runs exact, and entirely making the listener understand the essence of Mozartian style.

Billy Bigelow’s “Soliloquy” from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel is, for someone who grew up listening to Broadway musicals, the one most accessibly familiar to me, and the sentimental top favorite. I countered in an article that I wrote over 20 years ago that Carousel is an “operatic musical,” much like as in Opéra Comique, with its dialogue and song interwoven similarly. With its themes of spousal abuse and suicide, the piece spills over into verismo. The music requires singers with top-notch vocal training, and what a joy it is to hear Montague Rendall’s vocal means giving Billy’s long musings into imminent fatherhood such luxurious treatment. The British baritone here achieves the American vernacular effortlessly, and the shifting moods, from boasting high spirits to pensive reflection, are captured effectively, not least when Billy realizes, “…what if he…is…a girl.” The closing section, from “I gotta get ready before she comes,” is simply glorious, the unleashing of the tone to full-throttle just thrilling. This is a singing-actor with a voice.

The one drawback I found, though, and through the recital, is the balance engineering. It often favors the orchestra, and the singer’s voice somehow is made less prominent. I went back to John Raitt’s classic account in the 1945 Broadway cast recording, and that aural perspective confoundingly sounds much more natural than the ostensibly technologically superior digital one here. But make no mistake: Montague Rendall’s rendition takes its place proudly alongside Raitt’s and Gordon MacRae’s beloved accounts.

The piece that moved me the most, to tears actually, is the last selection, Mahler’s “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen.” This song about severe, depressive isolation and finding refuge and “Himmel” only in “Lieben” and his “Lied.” Montague Rendall’s high-lying baritone is deployed to exquisite effect, gorgeous in its sheen and legato, the tone dark and somber at first, and for the final stanza, matching the warmth in the orchestral accompaniment, the voice turning ever so slightly brighter and a glimmer of serene joy for the final phrases.

So, buy this, enjoy, and savor the emergence of the considerable gifts of a supreme artist.