I’ve always been of the opinion that anyone who disdains this great score or thinks the story silly ought to be confined to the TV room during a Marx Brothers retrospective and leave the opera house unsullied (and unsillied).

Il Trovatore is a drama about storytelling, and who tells a story better than Verdi does? Though Verdi, on occasion, may omit plot points that he doubts are “musicabile,” in Trovatore, those points usually occur between acts and are narrated later. Important sections of each of the first five of the opera’s eight scenes are taken up by someone recounting a story to someone else, confidante or chorus or (the Count) soliloquy. Then, in the opera’s final scenes, all these rival yarns knit together and turn out to have been a single labyrinth. The libretto’s penultimate line is the punchline of all opera punchlines: “Egli era tuo fratello,” He was your brother! Everything is set out neat, moments too late. Properly staged and sung, this ending should devastate and exhilarate at once.

Not everything about the Metropolitan Opera’s matinee thrilled me: notably, repeats of all three cabalettas were omitted, which would have startled Verdi and amazed the singers of yesteryear—quite recent yesteryears. As this cut the running time by less than a quarter hour, it strikes me as a false economy—the opera’s running time has already been shaved by two intermissions, probably so that a full dinner on the Grand Tier level can be marketed during the one that remains. On the off chance that much of the crowd has dropped by to hear excellent singing, why deprive them of thrills, which elevate enthusiasm and make the operatic experience more memorable? Ornamented repeats are not encores—they were decreed by the composer and, if done well, they raise the pitch of the dramatic experience.

“The suspense is terrible—I hope it will last,” Oscar Wilde’s Gwendolyn piously hoped—and doesn’t every stagecrafty presenter agree? But not in the current Met revival of David McVicar’s Trovatore, directed by Paula Williams, who seems to be embarrassed by extreme vocal emotions, and eager to distract us from them by inserting a violent duel now and then, where neither the music nor the libretto calls for them. But the decision not to repeat the cabalettas was not taken by Ms. Williams, in which case I apologize to her.

But let’s turn to happier matters: a lot of fine singing.

Rachel Willis-Sørensen, who has only sung Mozart at the Met heretofore, revealed a Verdi-sized voice, evenly produced, elegant in ornament (which made me even sorrier that both Leonora’s cabalettas were shorn), and full of creamy passion. She is a handsome woman and a fine actress, and I hope she sticks around and sings lots of middle-period Verdi for us.

The deep and full-ranging mezzo of Jamie Barton is hardly an unknown quality at the Met, but her Azucena hit a stylistic and dramatic intensity I had not experienced before. Her diction was crisp and energetic as she explored the haunted mother’s repressed past, and her dreamily nostalgic legato in both the Act III reminiscence and in “Ai nostri monti” called to mind many great Azucenas of the past—with whom Barton may be considered a peer. She was living this role, and while she sang, so were we.

Michael Fabiano is conquering much of the Verdi repertory these days—he just sang Gustavo in San Francisco—and one has never doubted the size and masculine force of his instrument. But the gentler, more romantic side of these roles sometimes seemed to elude him. It is therefore with genuine pleasure that I perceive he’s been working on those very aspects of his singing, and his “Ah si, ben mio,” for example, and his dueting with Barton both showed a gracious adjustment to the variations in Verdi’s drama. “Di quella pira” was not so effective as might have been expected—and here, I think, the Met’s (whoever at the Met) decision to hold him to once through, no repeat, and no high C—which Fabiano seemed eager to display (as no doubt he does at other houses)—produced an audible frustration. Restraint is not the byword of Il trovatore, never mind that Verdi didn’t compose that high C.

Igor Golovatenko’s beautiful baritone impressed me much last spring, in several performances of La forza del destino, and these are qualities one hopes for in a Count de Luna, a baddie with a yearning streak. By and large, Golotavenko satisfied one’s cravings, confronting the lovers with power and rage in Act I, and matching Willis-Sørensen in their duet. His “Il balen” easily filled the house, but I found it lacking in that legato, that internal romance that makes of the Count so nearly sympathetic a character. His frustration should have more soul to it.

Ferrando was yet another sturdy, easily handled performance from the reliable Ryan Speedo Green. Ferrando is the first of the evening’s storytellers, and his narrative should be memorable enough to stick in the mind when Azucena supplies her alternate version. Green achieved this with his accustomed suavity.

Daniele Callegari conducted vigorously, occasionally coming near to drowning out a solo singer or two, and thrashed through the Anvil and Soldiers’ Choruses as if determined to wake us all up. I did not think the wakeup call necessary, but since a couple of folks nearby had not turned their phones off, perhaps I am too idealistic.

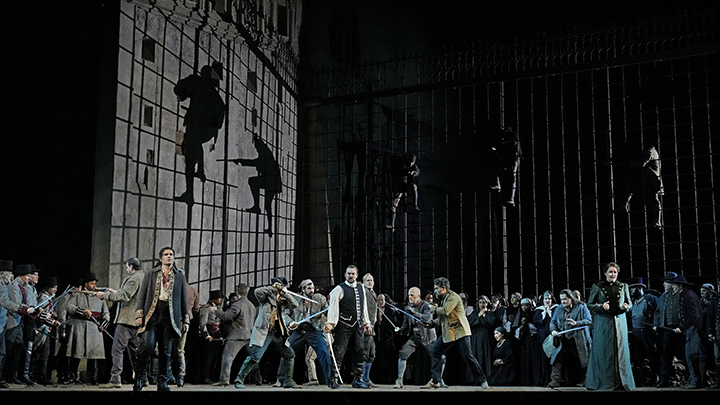

Charles Edwards’ turntable set is more reminiscent of ruinous civil war-torn Spain than I recall from earlier exposures, perhaps due to the elegance of Jennifer Tipton’s lighting. Brigitte Reiffenstuel’s costumes seem torn between the Napoleonic and the Carlist conflicts, and the black lace peignoirs seemed a bit high class for camp followers intruding on an army siege. But Willis-Sørensen’s heavy overcoat, as casual wear slung over the outfit in which Leonora planned her novitiate only to turn it into a honeymoon was ideal and suited the singer’s figure as well.

Photos: Ken Howard