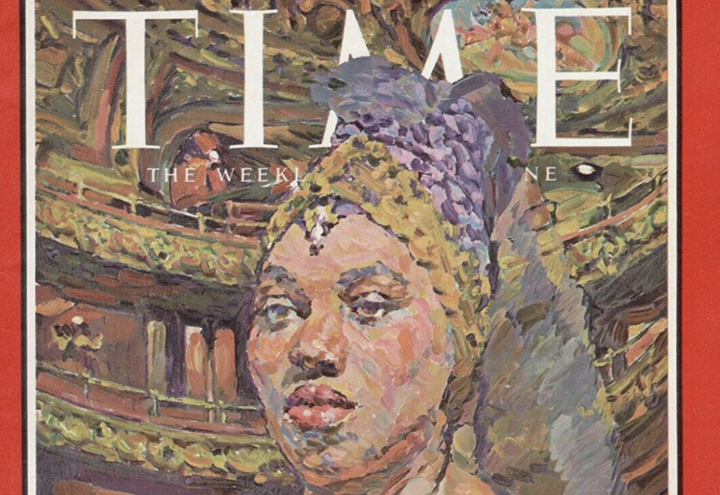

Time Magazine cover, March 10, 1961, shortly after Price’s Met debut

I only have 43 and I am not going to discuss all of them! That means I am sure to leave out somebody’s favorite and therefore I will be called ignorant, uneducated, and/or out of touch and living in the past. Be that as it may, I am only going to discuss my favorites – I repeat my favorites – and those that I feel are significant. They include studio, live, and video and though recordings of Il trovatore date back nearly a century, I am going to discuss only those that are from my lifetime – and, no, that isn’t quite a hundred years – but surprise! it does include current performers. Nor will I discuss any recording by the likes of what used to be the major recording company and whose stars used to include the greatest, e.g., Tebaldi, Sutherland, and Nilsson, but now resorts to selling recordings of unmistakable inadequacy. (Okay, I’ll say it: Bocelli as Manrico?)

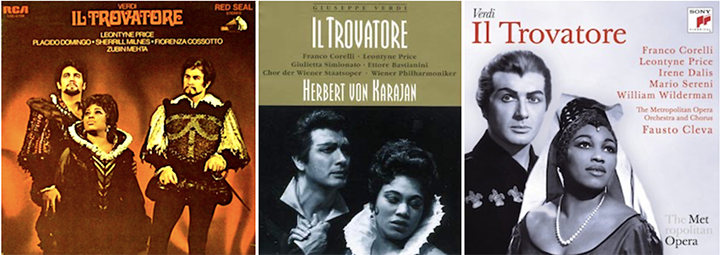

I will get right to the point and start with the conclusion: my favorite recording and the one that is at the top of almost every critic’s list, the one recording that if forced to have only one recording of the opera is the 1969 RCA with Leontyne Price, Fiorenza Cossotto, Placido Domingo, and Sherrill Milnes with Zubin Mehta conducting. The recording is absolutely complete, the first to be so. (Okay, it doesn’t include the ballet, which can be found on the Sutherland/Pavarotti/Bonynge version, but the ballet correctly belongs only on the French version, Le Trouvère.) When I say there are no weaknesses in the cast, that does not imply that each of those singers is not the best in their given role.

THE PRICE IS RIGHT

With the obvious exception of Aïda, the Trovatore Leonora was the role most associated with Leontyne Price as well as her most performed. When she received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1980, Zubin Mehta quoted a New York critic saying “Leontyne has come down from heaven to sing Il trovatore for us.” As said above, she made her Met debut in the role on January 27, 1961. She had already recorded the role for RCA in 1959 with Elias, Tucker, and Warren. There will be those who argue she was better in the earlier recording, perhaps, but a decade later she reveals a further mastery of her art in a performance distinguished by a richer sound and still those glorious high notes. Her “D’amor sull’ali rosee” is so ravishing it is one of the very few times one wants to applaud at a studio recording. She also recorded the role again in 1978 with von Karajan for EMI and though she is still great, it pales by comparison to the earlier performances, as does the entire recording. For the record, she does sing the Kitty Carlisle-hi-Cs, or at least one of them in the Karajan, but not the earlier ones. Her only high note interpolation besides the standard D-flat at the end of Act I, is one in the RCA when she is pleading with the Count and it’s truly exciting. The Met legitimately released the matinée broadcast of February 4, 1961 a few days following the debut (that’s also available) but the more legendary performance is the Price, Simionato, Corelli, and Bastianini, von Karajan conducting from Salzburg a year-and-a-half later discussed below. It almost nudges out the RCA for top spot! As a bonus, Leontyne sings both KC-hi-Cs gloriously!

RCA 1969:

Rival recordings

Back to the RCA; falling into the great tradition of Italian mezzos such as Stignani, Barbieri, and Simionato, Fiorenza Cossotto is little short of perfect as Azucena. With her vivid vocal acting, at times the voice is like molten lava, it just pours forth. The reason she is not in the cover photo is because that photo was done for the new Met production which was done with Grace Bumbry, an equally superb and fiery Azucena. I was surprised recently when I was closely following the score that when Cossotto sings what sounds like it would be an interpolated high C near the end of the duet with Manrico is actually in the score. Very few mezzos take it (or are capable of taking it). As she aged, the voice turned sort of into a buzzsaw. I once illustrated a duet from Adriana between her and Mirella Freni in 1989 as:

Be that as it may, Cossotto was the fabulous Amneris at Price’s televised farewell in 1985, sixteen years after this recording. This was Placido Domingo‘s first complete operatic recording with many, many to come. As always, he sings with an innate sensitivity and cultivated grace while impressing with his beautiful voice. Despite that, compared to Corelli he seems a bit dull – but who isn’t? Sherrill Milnes fits the Count perfectly, nothing more need be said. It turns out that the usually dull Bonaldo Giaiotti is probably the best Ferrando of the lot. As a bonus, Zubin Mehta leads a surprisingly sensitive and sensibly paced performance. Like his recordings of Turandot and Fanciulla, they are the the reference recordings. I quote from a 1973 review by Kenn Harris in his Opera Recordings book: “The tenor is perhaps miscast in so heavy a role as Manrico. Young tenors who push their voices in such heroic parts don’t always get to be old tenors. Sherrill Milnes, on the other hand, is in no danger of harming his voice in the role of Di Luna, singing with eloquence and power, although offering little expression of the Count’s villainous nature.” Wow! Was that ever wrong!

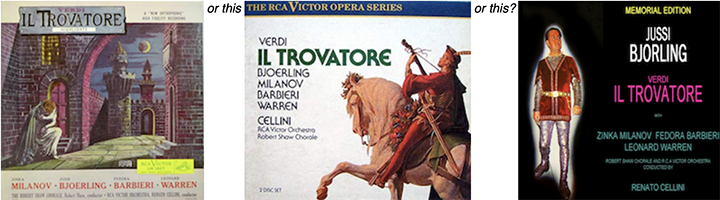

Is it this one: or this or this?

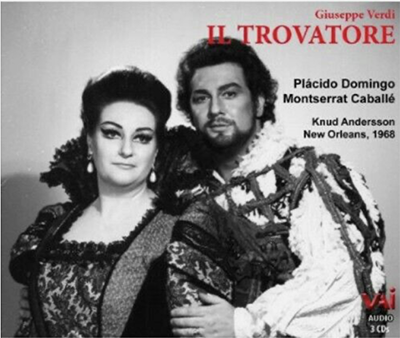

In my lifetime, the great Leonoras have been chronologically Zinka Milanov, Maria Callas, Leontyne Price, Montserrat Caballé, and Anna Netrebko. That is not to say there haven’t been other wonderful ones (Tebaldi, Stella, Arroyo, Sutherland, Scotto, Meade, Radvanovsky immediately come to mind), but these five will go down as the “legendary” ones.

Taking them in order, other than Leontyne, the recording that most critics and the others of us reference is the first RCA (there are two others both with Price): RCA 1952 with Zinka Milanov, Fedora Barbieri, Jussi Björling, and Leonard Warren; Renato Cellini conductor. With her usual modesty, Milanov has described this Trovatore as her finest achievement for the gramophone. Umm…, as stated every time I mention her, I am not a Zinka fan. Undoubtedly, the voice is perfect for the role, sumptuous, superlative in color and weight, and occasionally she floats a note in the way which gave her a reputation. But she is heavy-handed with the coloratura and her sliding in and out of notes is not what could be considered portamento. Given her prestige and reputation, Zinka must have been more than a little peeved when RCA released the Björling Memorial Edition with his name somewhat more prominent than hers. However, Björling’s Manrico radiates elegance and refined legato. There is no more beautifully sung Manrico than Björling’s. That makes up for what he lacks in excitement … Corelli he ain’t. Warren’s di Luna can be described the same way – aristocratic, elegant, perfectly sung with class and precision and a tad dull. Barbieri’s Azucena is somewhat the opposite, a bit demented as Azucena should be. Barbieri sings better here than in other versions. Cellini is not the most inspiring conductor. It is severely cut. So, not my favorite Trovatore; others will disagree.

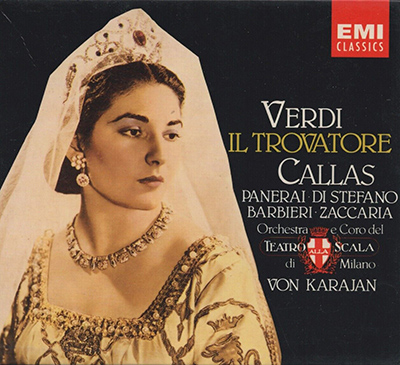

The same can be said about the Callas Trovatore: EMI 1956 – Callas, Barbieri, DiStefano, Zaccaria; von Karajan. Its singing, sound (it is mono and if it were not for EMI producer Walter Legge’s stubbornness regarding stereo, it easily could have been), somewhat inadequate casting, and its heavily cut edition keep this from top consideration. Even so, it is still worthy of recommendation … albeit not mine. In terms of sheer sound, Maria Callas’s Leonora must rank behind Milanov’s and many others as well; but where realization of musical values is concerned, it is probably the best on records. Her portrayal of a desperate Leonora is riveting, her voice is at its best and fully under control, and her deep knowledge of bel canto style and her special gift for word-painting makes this portrayal the standard for others to follow. If only her voice wasn’t so unattractive. That ends the subject for me.

Oh, yes, she was the first to record the “Tu vedrai” cabaletta, albeit one verse. In spite of all that, the pairing of Callas and Karajan in an opera recording along with an orchestra, La Scala, versed in the Verdian performance tradition, brings it back into top consideration. Herbert von Karajan has a long, distinguished history with the opera at least if you disregard his final recording from 1978 also on EMI which for the most part was a disaster … Price well past her prime, a dreadful tenor (Bonisolli), dull baritone, albeit an exciting over-the-top mezzo (Obratzsova), and conducting that draws attention to itself – either too loud, too soft, too slow, too fast. But in 1956, Karajan was fully in control and most critics feel this is the best conducted Trovatore and thus reaches legendary status. It is a highly dramatic and exciting performance, combining a true sense of italianità and powerful orchestral presence. The result is exhilarating and one has only to sample the violins in the Act I finale to understand the kind of magic Karajan did with this score. On the downside, Giuseppe Di Stefano is seriously over-parted. He certainly lacks the insight that Callas has both musically and histrionically; being impassioned is not the same thing. This is a singer who squandered his ample gifts. Björling is everything this tenor is not. Both Barbieri and Rolando Panerai are fine. All in all, though, Callas remains legendary in the role even though she performed it very little. If one really wants Callas, other than for the conducting, there are several live performances with some more exciting partners such as Björling (if you can find it – you can’t), Simionato, or Warren.

If one really wants Karajan, again stick with the live Salzburg Karajan performance. Salzburg July 31, 1962 – Price, Simionato, Corelli, Bastianini; von Karajan. The broadcast was first available on pirate labels but later released legitimately on DG. Each of the soloists are not only in superb form, but the best in each of their roles. Obviously, this is the time to talk about Franco Corelli. There are those who lament a lack of refinement and subtlety in performers such as Corelli and Del Monaco in this opera. Trovatore is the loudest, trashiest, i.e. demented, most absurd and thrilling of Grand Operas and what it doesn’t need is understatement. It wants singers whose voices can fill an opera house. And no singer could fill an opera house like Franco Corelli, “Golden Thighs” as he was nicknamed. He was the total opposite of Björling, yet the two tenors are usually voted the two most popular tenors. Corelli was the Italian tenor whose powerhouse voice, charismatic presence, and movie-star good looks earned him the adoration of opera fans from the 1950’s until his retirement in 1976.

Mr. Corelli was faulted by some for the sheer athleticism and raw passion in his singing; those same qualities drove other opera buffs to ecstasy. The vibrancy and white heat of Mr. Corelli’s singing allowed him to shamelessly prolong full-voiced, climactic top notes and Il trovatore was the ideal opera to showcase that talent (or fault, to the ears of critics). Corelli grandstands shamelessly but irresistibly, and although he often sang “Di quella pira” down a semitone to end on top B rather than C, he always threw in a huge top D-flat at the end of Act I and some stunning extended Bs and B-flats elsewhere. Corelli’s studio performance on EMI fails to match the excitement of any of his live performances. Price, too, is simply divine: thrilling, poised and deeply moving, managing those same D-flats, trills and extraordinarily agile coloratura to ornament the great line of the Verdian spinto soprano. You will never hear majesty and power as displayed here by both Price and Corelli. They are arguably better in the Met broadcast of February 4, 1961, but Simionato, Bastianini, and von Karajan shift the balance in favor of Salzburg.

Salzburg 1961:

-R&index=1In my pantheon of great Il trovatore recordings and performances comes one that ties with the 1969 RCA for first place. It is not the 3/17/73 broadcast from the Met but the tour performance that followed nearly a month later: 4-11-73 Met – Caballé, Cortez, Domingo, Merrill, Plishka; Cillario conducting. I have already mentioned it in the previous installment with the sample of the Caballé traversal of the great Act IV scena. As I said, it is a totally demented performance as any good one of Il trovatore should be. Who can say why one performance with mostly the same cast works better than another? What ignites the audience? This audience surely knew because they don’t even let Paul Plishka (instead of the mush-mouthed Ivo Vinco, aka Mr. Cossotto) finish his narration before they burst out in applause. Same thing happens near the end of the Azucena/Manrico duet. And when those scenes are completed, the audience goes berserk. Perhaps it’s the presence of the replacement for Mrs. Vinco, i.e., Fiorenza Cossotto, in the both visually and vocally striking Romanian mezzo Viorica Cortez.

Cortez made her Met debut as Carmen in 1971 and besides Carmen and Azucena, she also sang Amneris, Dalila, and Giulietta in Hoffmann. I believe her only Met broadcast was with Scotto as the Princess in Adriana. Her performances and fame were limited, as getting out of her home country of Romania was always a challenge until she became a French citizen. After that she was overshadowed by the much-recorded Cossotto, Bumbry, and Verrett. The voice was beautiful and very dramatic. She was electric as Azucena. In this performance, Placido Domingo manages a bit more excitement though the Cs (or really Bs) still just never quite make it. When I saw Robert Merrill back in 1964 as the Count, I remember the talk amongst the standees that Merrill would have been booed if the voice itself wasn’t so beautiful. He just stood there emoting nothing – the quintessential park-‘n-bark performer. Seven years later, the only thing that had changed was the voice was no longer beautiful; in fact, the ‘Balen’ goes completely awry – wrong notes, wrong tempos, just terrible, but at least he doesn’t really damage the performance. Montse just about makes him disappear in the duet. Fabulous performance, though! Unfortunately, I cannot find it online any longer. Find it if you can.

Price and Caballé are my #2 and #3 favorite sopranos and not necessarily in that order. (It depends on the day of the week.) #1 is and always will be Renata Tebaldi. La Sublima also recorded Trovatore; it was a major recording with an almost all-star cast back in 1956 on Decca: Tebaldi, Simionato, Del Monaco, Giorgio Tozzi, and as the Count, Ugo Savarese – you say, “who?” I can only assume that Bastianini was not available … major let down. Del Monaco typically is loud and obstreperous and sweating testosterone. The great Simionato and Tozzi remain unscathed and are excellent. But … poor Renata. She might be the best Leonora (Forza) but not this Leonora. Despite being in prime vocal condition, she just is not cut out for this florid music and we feel her discomfort. However, she does surprisingly well especially with the first aria and its cabaletta. No one sings it with a more beautiful sound. Just don’t expect to hear any “little notes,” much less a trill – and the role of Leonora, this Leonora, is filled with trills. The “D’amor sull’ali” turns a bit listless, but one can still luxuriate in the glorious outpouring of sound. Still, she was so happy with it that she was singing the “Tacea la notte … Di tale amor” in many of her concerts even as late as 1966 and again: surprisingly well. Judge for yourself:

Definitely deserving of mention is the other Renata, Renata Scotto, if for no other reason than she opened the Met 1976-77 season in Trovatore along with Luciano Pavarotti back when they were speaking to each other. The following season she sang a broadcast of it on April 9, 1977 with Verrett, McCracken, and Quilico. I didn’t think much of it (it’s available on Met On Demand). In early 2023, Chris’s Cache on Parterre featured several in-house recordings of Scotto and an in-house recording in Boston from a couple of weeks after that broadcast. Whether it was because her different partners, Cossotto and Bergonzi, or from a two week rest, she was in superior – for her – voice. Yes, the usual earmarks of her singing are all there – squally tone, pinched high notes, and an innate sense of how the music should go. Whatever one might think of her, she was a superb singing-actress. Pitch might be forced at times, but Carlo Bergonzi remains the supreme Verdi tenor and Cossotto the supreme Verdi mezzo. Recorded sound here is a bit cavernous but quite listenable. A rewarding performance.

THE ‘BEL CANTO’ TROVATORES

Although separated by about a quarter of a century, two commercial recordings were made at the end of the previous century and they could not offer more different ideas of what makes up “bel canto.”

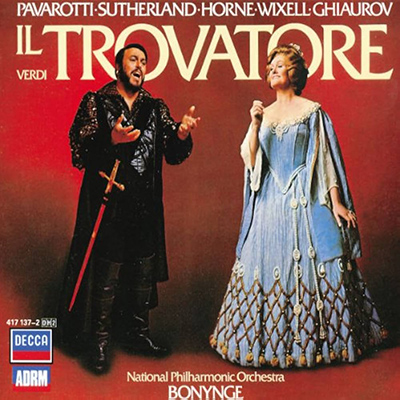

Let’s start with the 1976 Decca – Sutherland, Horne, Pavarotti, Wixell, Ghiaurov; Bonynge debacle. The idea was to supposedly present the opera in a “Donizettian” way including embellishments and the like. Bonynge also incorporates some details of the 1857 Paris version, Le Trouvère. Bonynge has demonstrated again and again that he is principally drawn to the decorative in music, with structural continuity and dramatic intensity low down on his list of priorities. The failure here has more to do with the cast than anything else; in fact, the recording was held back two years before release, I suppose so some of it could be doctored or whatever. Joan Sutherland, La Stupenda, is in errrr… late career voice, much of the singing is unsteady, not a usual Sutherland trait, though her mooning manner is. The role never really suited her although not disastrous as her Adriana recording is. Some of her ornamentation is at best incongruous and at worst weird and disturbing. In my opinion, ornamentation should enhance the vocal line not necessarily draw attention to itself or break the flow of the melody. The embellishments in the opening arias do just that; they seem out of place. Strangely, they are in the score of the French revision with the exception of the actually written high D-flat following the double Bs and Cs in the “D’amor,” that breaks the line of the climax and totally ruins the mood of the beautiful melody; technically though it’s not an embellishment. The other interpolations are standard. Some you win, some you lose.

Sutherland is certainly suited to much of the Verdi she sang, but Marilyn Horne is not. I have heard Horne described as The Greatest Singer in the World while Sutherland as The Voice of the Century. Complicated, but I get it. Certainly Horne sings all the notes – written and unwritten – brilliantly; they just don’t gel. It is a pleasure though to hear all the trills in “Stride la vampa” so superbly rendered. Ingvar Wixell is equally misplaced; he just isn’t an Italianate baritone, though he does sing a beautiful “Il balen.” Luciano Pavarotti has the right kind of voice for Manrico but he pushes by trying to make it sound a couple of sizes bigger. As for Nicolai Ghiaurov, the moment he started singing, I sat up. Immediately one knows this is a major voice. But somehow, he’s just not quite right either, perhaps he just overwhelms the part.

The recording is not the misconceived enterprise I’m seeming to indicate. There are many good moments, interesting ones. The real draw though is that this is the only studio recording to offer the complete ballet, not counting any recording of the French version. I love opera ballets and all that have been excised lately should all be reinstated. However, a scene otherwise 12 minutes long, stuffed with 26 minutes of ballet, adds up to a pretty misshapen and indigestible meal as I see it. There is a solution and I’ll get to it soon.

Sutherland and Pavarotti strangely are much better some eleven years later at the Met in what was to be Dame Joan’s last performance at the Met, 12/19/87 Met – Sutherland, Verrett, Pavarotti, Nucci; Bonynge. Everything here works for her and she remains La Stupenda. Shirley Verrett is also pretty stupendous. One may ask, how is it that Sutherland’s final Met broadcast is so assured and perfect and the Decca a flop? Perhaps the studio draws more direct attention to the voice, maybe it was just a good day, otherwise, ¯\_(?)_/¯

The other commercial (as opposed to studio as it is live from La Scala) of the “Bel Canto” version is the 2000 Sony – Frittoli, Urmana, Licitra, Nucci; Muti otherwise “The Muti” recording. My immediate thought after a few minutes of listening was, “Quale orror!” To put it mildly, this is fast and hard-driven. Yet somehow, by the end of Act II, I found myself getting into it and ultimately I went back and listened to it again with a greater appreciation. There is a sense of forward movement and theatrical excitement that makes the performance uniquely satisfying. Muti’s idea was to strip off the verismo varnish applied by preceding generations, to reveal an undreamed-of bel canto refinement. Muti’s idea of bel canto is very different than Bonynge’s, to say the least! Gone are ANY interpolated high notes! (More on that later.) I’d like to think they are not missed, but they are. The singers are all good though not memorable compared to those already mentioned. It is good, though, to hear Salvatore Licitra again. This is a recording that should be heard at least once. Unfortunately, it is not online though there are plenty of excerpts from it. I doubt that works, though, as it is the totality of the performance that makes this conception work.

In the summer of 2007, Bel Canto at Caramoor at the exquisite estate in Katonah, NY performed their true “Bel Canto Trovatore” with Juliana Di Giacomo, Ewa Podles, Francisco Casanova, and Daniel Sutin under the direction of Will Crutchfield. The capable cast are not the important names here, but the conductor and musical scholar is. His scrupulous detective work produced a Trovatore that could be viewed as the apex of bel canto, with unusual cadenzas and ornamentation adopted from scores used by performers of Verdi’s day. The other draw was a rare opportunity to hear the magnificent Polish contralto Ewa Podles.

*Before I end this I should say that I am not really totally obsessed with high notes. In almost every review or article I’ve read on Trovatore, there is some sort of mention of them. In fact, the reviewer in The Metropolitan Opera Guide to Recorded Opera spends four out of five paragraphs of his opening remarks discussing them and the cuts. In short, I strongly feel that in most cases, omitting the usual high note at the end of a cabaletta or act will cause the ending to fall flat. Caballé is the only singer I’ve ever heard who can consistently sing an ending with such force as to not make one miss the high note … well, almost anyway. Additionally, regarding ornaments, the double arias of the bel canto period were usually written with two verses and the second for which even the composer expected the singer to provide their own embellishments. It is the style, it is the period. Muti is wrong to omit them.

For the record, Verdi revised Trovatore for the Paris Opèra in 1857. This is the Paris version, Le Trouvère. The revisions are relatively minor and some of them found their way into the standard Italian original. Some good things, some – well, I’m not so sure … maybe it was the français. The big difference, of course, is the inclusion of the ballet. This was the last thing I listened to and it needs more listening. At the very end, the ending is expanded; I felt like I was in the world of the trial scene at the end of the original version of Don Carlos.

DEMENTED AND FABULOUS!

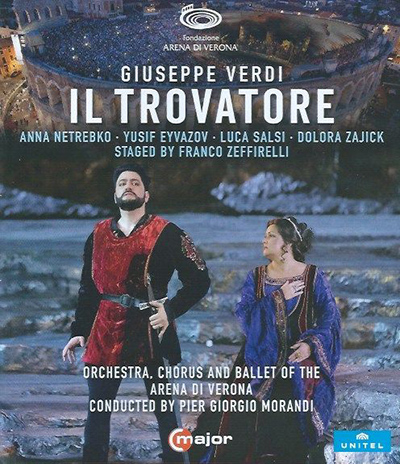

This leaves only one more performance to talk about, and it’s a doozy! It’s also the only video I’ll talk about though there are three from the Met (1988 in the Melano/Frigerio production with Marton, Zajick, Pavarotti, and Milnes; 2011 in the current McVicar production with Radvanovsky, Zajick, Alvarez, and Hvorostovsky and again in 2015 with Netrebko, Zajick, Lee, and Hvorostovsky his last Met performance), as well as a super macho, and generally offensive, version from Covent Garden 2002 with Villarroel, Naef, Cura, and Hvorostovsky, and many others from all over. But it is the most recent from five years ago, 2019 from the Arena di Verona, with an incredibly excellent Anna Netrebko; Dolora Zajick, yes, again 31 years after her Met debut in the role and showing and sounding every one of those 31 years; a bearable Yusif Eyvazov (the now ex-Mr. Netrebko), and a barely bearable Luca Salsi Italy’s latest excuse for a baritone.

It’s hard to believe that when Netrebko first sang the role at the Met, everyone felt that she was just about the equal of anyone named in this essay. No, the voice isn’t as beautiful as Leontyne’s; no, she can’t float a pianissimo like Zinka, nor can she handle all the little notes like Montse, but she sings all the notes and sings them excellently. She is the only diva to sing BOTH verses of the Act IV cabaletta in a live performance which makes for a solid 18 minutes of very challenging singing followed by another 8 minutes of duet with the baritone. And she can act. And she can ride a horse. What she can’t do, or doesn’t do, is add any of those interpolated but necessary high notes, like at the end of Act I and the end of the just mentioned duet, that would otherwise put her at the top of the list. So, there is a current-day singer I admire!

I would name the horses Arena and Verona.

What makes this production so unique and demented is it’s the Zeffirelli production that out-Zeffirellis any other Zeffirelli production. And it’s all fabulous! So over-the-top and I love every minute of it. It culminates at the end of Act II with the set opening up to the most elaborate reredos (the large altarpiece behind an altar) I have ever seen… and then the horses come on and Trebs and Yusif ride off on them. FABULOUS!

Did I mention, the ballet is done? Here is the perfect solution. It is chopped up and the unsuitable music eliminated and split between its supposed usual place in the Act III soldiers scene and the more appropriate camp scene at the beginning of Act II. This is the way it should always be done.

And done this is, except, as promised, you can find the Opera News parody article I mentioned scanned here.

Instead of reading all the above, you could have just jumped here to know that my #1 choice – the must-have version – is the RCA with Leontyne and Mehta conducting. My alternate choice if you can find it is the 4-11-73 Boston Met performance with Caballé, Cortez, Domingo, and Merrill. What you can find easily is the 1962 Salzburg with the dream cast: Price, Simionato, Corelli, and Bastianini with von Karajan conducting. None surpass these artists. And #4 is the video of the Verona dementia with Netrebko, commercially available.

Starting tomorrow, there is another Trovatore revival at the Met. I wonder if any of it will ever be mentioned in an update of this essay…

“Quale orror!” ~ Andy