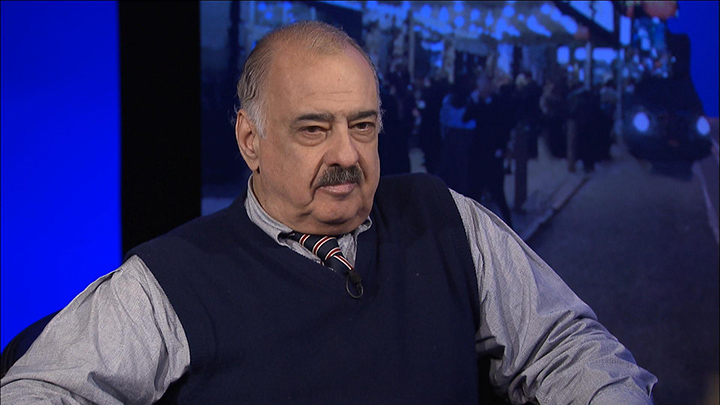

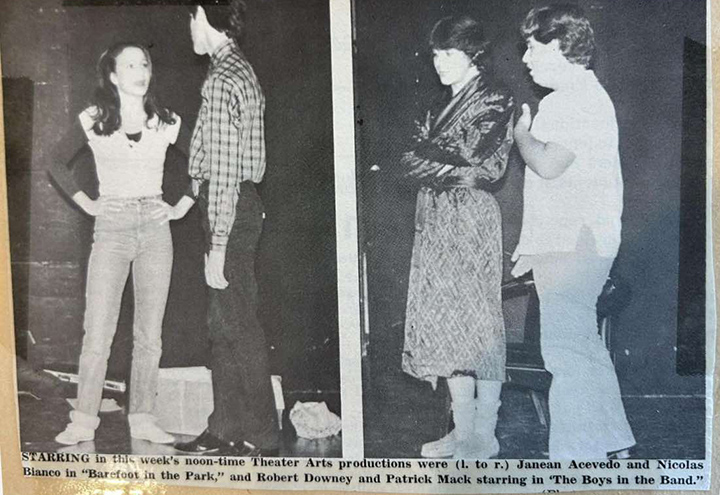

I think I may be the only person I’ve heard of who became interested in opera initially through books. In High School, we had an incredible theatre arts department, I’m sure primarily because of funding by our drama teacher Eugene Jellison because those $3 admission tickets certainly weren’t renting our costumes and buyin’ all that lumber and paint. Nor do I think the school board was interested in funding a fairly incredible production of Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour in 1981. (Hell, in my senior year I was in a lunchtime presentation of a scene from The Boys in the Band with yours truly as Michael and Robert Downey, Jr. as my lover Donald.) Oh, it was Santa Monica and we were rife with budding movie stars.

But I digress. In that same senior year, I was assigned my first production to design. Since I was already doing the theatre arts posters and was the cartoonist on the school paper, I guess it was a natural progression. The play was Molière’s The Miser and I proceeded to check out books from the library on theater and, by extension, opera, to get ideas for sets. One of those books became a gateway drug for me: The Splendid Art of Opera; A Concise History written by Ethan Mordden, which had just been published the year prior so it must have been bright and shiny on the library shelf (which was always this bibliophile’s aphrodisiac).

Now if you ever need to give someone a crash course on opera, Ethan Mordden is your man. The book takes you all the way from Monteverdi to Britten and beyond in roughly 400 chatty pages. He’s scholarly but not overly dry and he writes with a twinkle in his eye. He also dishes some of the dirt you wouldn’t normally hear in someone’s PhD dissertation. It’s like having coffee with a pal who knows absolutely everything about opera. Plus, he writes like he was in the room when it happened with all of them. (p.s. I’m still not friends with Signor Monteverdi or Mr. Britten, but there’s always hope).

In spite of having no resident company in Los Angeles where I could actually see opera until 1987, from ‘82 through ‘83 there were some pretty fabulous telecasts from the Met. The Zeffirelli Bohème. The Gala concerts with Troyanos & Domingo, Domingo & Milnes, and Price & Horne (!). Idomeneo, Rosenkavalier, Sutherland’s Lucia, Tannhaüser, Hansel und Gretel, Don Carlo, Les Troyens & Ernani, plus the Centennial Gala which had me in apoplexy for an entire day. Talk about an operatic starter kit! Yet I wouldn’t have had a clue what to think about any of it if I hadn’t read Ethan Mordden.

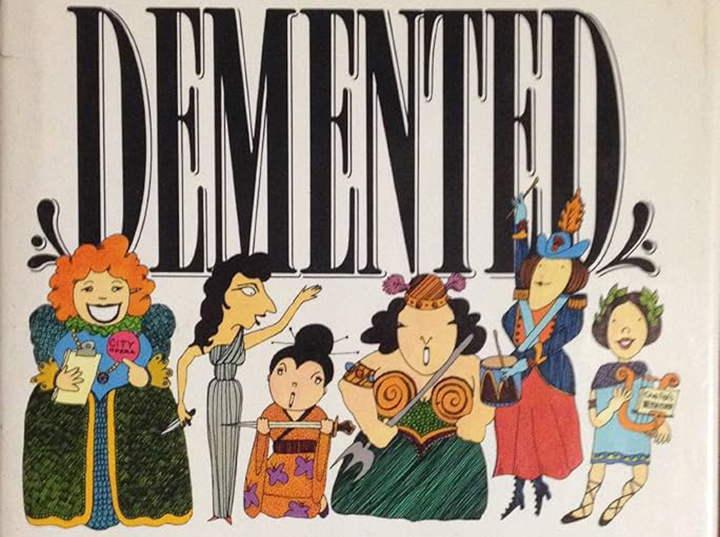

Then in 1984, Mr. Mordden published Demented. Beloveds, let us bow our heads. Therein he coined phrases that are still part of the gay-opera lexicon to this day. A classic. Mind you I couldn’t ever give up Peter Conrad’s A Song of Love and Death or, heaven forfend, my volumes of Andrew Porter’s New Yorker reviews (which were my college education). Yet I think Demented is the one I’ve returned to the most over the years. It’s a literal moveable feast of diva worship. The operatic equivalent of brunch with your opera Auntie Mame. It is beyond doubt that somewhere between Mr. Mordden and Mr. Porter was where I inherited my sense of humor about opera and I will be forever in their thanks and debt.

I’ve kept up with Mr. Mordden over the years through his volumes on Hollywood and Broadway but Demented was his last work in that field besides his Opera Anecdotes (which, p.s., was updated not too long ago). So when my current editor pointed out that Puccini Operas on CD: A Conversational Guide by Mr. Mordden had just appeared on Amazon, I had it on order before you could say Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini.

My disappointment started shortly after it arrived. Back in 1980 Mr. Mordden published A Guide to Opera Recordings, not nearly as comprehensive, say, as The Metropolitan Opera Guide to Recorded Opera (I’m on my second copy), but chatty and I’m always fascinated to learn new things and see how my tastes align with others.

The new Puccini is a slim volume and obviously self-published. It’s under 100 pages, none of which are numbered. Now, the Met guide hasn’t been updated since ‘93, so I was looking forward to fresh conversation. Unfortunately, it appears that time has mostly stopped in the Mordden manse. He’s still talking about 78’s and refers to anything recorded by RCA regardless of the era as “Victor.” It’s quaint. All those 78s to which he refers can undoubtedly be found on the Nimbus label or surely YouTube now. At one point he refers to Puccini’s Edgar as having only one commercial recording. That was true up until 2006; now there are three.

The author opens with a short primer on verismo starting naturally with La Gioconda, and working his way through Cavalleria Rusticana, Andrea Chenier, and then landing on L’Amore dei tre re (an under-recorded opera if ever there was one and featured last year on Chris’s Cache). He briefly mentions touchstone recordings of each. He prefers the Naxos remastering of Callas’s first Gioconda (which makes me curious), but the conversation stops with Tebaldi and Bergonzi’s issued on Decca in ‘67.

I’d have loved to hear what he had to say about Eva Marton and Violetta Urmana. (Our own Andy Knapp opined here on that earlier this year.) He also seems unaware that back in 2006, Orfeo issued a live Vienna performance of Chénier from 1960 with Renata Tebaldi, Franco Corelli, and Ettore Bastianini is such superb voice (and good sound) under Lovro von Matacic that it practically crackles with theatrical intensity. Montserrat Caballé and Luciano Pavarotti are mentioned in the Chénier portion, but not their Gioconda which is odd since the latter roles were actually a better fit for all concerned.

In the preamble to the start of the Puccini section, the author advises that he won’t be wasting time on ‘unnecessary performances’ like the 1977 EMI Turandot under Alain Lombard featuring Caballé, Mirella Freni, and José Carreras, dismissing it as “[capable] forces without commitment or individuality.” Consequently, I almost fell out of my chair when, in the chapter on Manon Lescaut. he wastes ink on the 1987 Decca release with Carreras and Dame Kiri te Kanawa asleep at the wheel. To give it context, though, it is only to praise the conducting of Riccardo Chailly.

The chapter on La bohème starts off with Beniamino Gigli and Licia Albanese under Berrettoni then segues through Toscanini, Beecham, Erde, Serafin, and Schippers before we reach the finale ultimo with Herbie von Karajan. But that leaves Scotto & Raimondi, Caballe & Domingo, Ricciarelli & Carreras, Reaux & Hadley, Dessì & Sabbatini (new critical edition), Hendricks & Carreras (one of my faves), Te Kanawa & Leech, Gheorghiu & Alagna, Frittoli & Bocelli (lord help us), Netrebko & Villazon, Amsellem and Haddock, and Haymon & O’Neill (in English) out in the cold. Mind you, not all of those couples deserve to be rescued from the Barrière d’Enfer, but It’s like the Cafe Momus closed up shop in 1972.

We have a similar problem with Tosca, although here the author seems very individual in his tastes. He very bravely opines that while Maria Callas is in great voice for her classic 1953 recording under Victor De Sabata, “[it’s] not quite a Tosca instrument (his italics), lacking the creamy tone the music needs, for instance the rich sound of Leontyne Price.” My guess is he’ll probably have to enroll in the Witness Protection Program after that remark circulates, and I concur.

He prefers Price on the live Met relay (1962 issued on Sony CD in 2011) with Franco Corelli and Cornell MacNeil to the Decca Karajan 1962 (a “Hark how the bells noisetacular”) and Mehta (1972; dismissed as, “A slack affair by major voices on an off-night). Giuseppe Taddei’s name goes unmentioned (?). Mr. Mordden then praises Mme. Régine Crespin under Mehta live at the Met (a pirate I just ordered) with Gianni Raimondi and Gabriel Bacquier.

He also extols the virtues of Renata Scotto as La Tosca with Placido Domingo and Renato Bruson whom he deems the best of all Baron Scarpia’s under James Levine (Gobbi & Taddei just called their lawyers). Here we are, brothers, and his arguments in favor of this particular interpretation are very persuasive. This recording is indeed one of my favorites and it’s a performance with a special vitality and attention to detail thanks to the soprano and conductor.

I have a pet theory that just like our first sexual experiences can mark our desires for the rest of our lives, positive or negative, so, too, can our first exposure to an opera performance — especially on recording — define our tastes forever after. Mr. Mordden proves this with his devotion to Victoria de los Angeles, a wonderful artist no doubt but one whom I always thought was never ideally caught in the studio. For me, she always displayed a frailty above the staff that bordered on the inadequate in opera. I want that thrill of plangency. He dubs her timbre in Madama Butterfly “ideal” (in mono 1954) which tempts me to revisit and reconsider. (Aside: I have since and I still find her wanting.)

Still after going through Toti dal Monte, Licia Albanese, Renata Tebaldi, and then Callas and Freni under Karajan, he leaves quite a few sopranos on that hill waiting to get married. De los Angeles’s and Scotto’s first assumptions warrant his scrutiny but, once again, 1974 seems to be the year time stands still. Anna Moffo and Leontyne just sent each other condolence cards.

Carol Neblett, 1977 on Deutsche Grammophon, claims the top spot as queen of the gold miners in La fanciulla del West, and he’ll get no argument there from me. But he mistakenly claims that Mehta opens previous cuts so we get all of the score. That didn’t happen until Leonard Slatkin in 1991 on RCA with Eva Marton and Dennis O’Neill or, even better, Melody Moore on Pentatone under Laurence Foster in 2021. Those performances, too, go, sadly, unmentioned, because I’d love to hear Mr. Mordden hold forth on both.

He also singles out Mario Del Monaco’s “Or son sei mesi” on the live relay from Florence opposite Eleanor Steber as “among one of the most spectacular vocal feats in postwar opera,” proving that he’s never sampled Lorin Maazel’s La Scala performance from 1991 on Sony where Domingo is captured in what may be the best evening of his entire career, taking the climactic phrase of that aria in a single breath where Del Monaco takes two. Domingo does the same trick on the DG recording, but you never know about the cleverness of engineers in the control room. (I heard him in the role twice and I never got that trick in the theater.)

La Rondine gets a brief flyby with its three major recordings, none of which really need detain us for long.

Then we get this humdinger ,and I shall quote verbatim from the text: “As I’ve explained I’m not reviewing the ‘Scotto Trittico’ because of Sony’s stingy tracking – a total of five queues for the entire package. Moreover these are questionable performances in part. And it isn’t a Scotto Trittico, anyway. She sings in the first two of the three titles, but cedes Lauretta to Ileana Cotrubas.” Oh, bitch. Mr. Mordden wasn’t riding that churlish high horse in his previous compendium back in 1980 when he had nice things to say about it.

He proselytizes with the expected admonitions for the De Los Angeles, Tebaldi, and Freni versions and lands on the 1991 EMI Pappano set as the best, which at least brings him into our era if not the current century.

Things heat up considerably with the chapter on Turandot. He pointedly reminds us that Puccini had hoped for Gigli to sing Calaf at the prima but another lyric tenor, Miguel Fleta, was deputized instead. He also mentions the luxury casting of Giacomo Rimini as Ping without mentioning that he happened to be the husband of the Principessa in question, Rosa Raisa.

He then takes up the banner for the original Alfano finale before Toscanini ripped it to shreds. He praises Decca for the first commercial recording of said finale way back in 1989 with Josephine Barstow and Lando Bartolini under John Mauceri. He also champions its inclusion on the most recent Pappano EMI release with Sondra Radvonavsky, Ermonela Jaho, and Jonas Kauffman, saying that Alfano I in context “doesn’t just end Turandot but completes it”. Thank you. After naming the singers, though, he doesn’t comment on the actual performance at all which is decidedly un-conversational for a conversational guide.

The problem with this conversational guide is that it ignores much of what has transpired since I myself became an opera fan way back in the 80s. Plus, in trying to be conversational rather than comprehensive by avoiding those aforementioned “unnecessary performances,” we’re denied those witheringly caustic bon mots that we know Mr. Mordden has in his arsenal. There’s nothing more difficult than reviewing a great performance. You can only say something is ‘magnificent’ in so many different ways. My friends and I used to have a saying, “if it’s good, it’s great, but if it’s bad, it’s better”. How I would have relished Mr. Mordden’s thoughts on some of the lesser assumptions not mentioned. Nothing like a little velvet gloved vitriol.

As I mentioned, it’s a slim volume — so slight, in fact, I accidentally threw it away with some accumulated junk mail I’d sifted through on my dining room table. (I did manage to retrieve it once I’d realized what had happened.) If you enjoy Mr. Mordden’s writing it won’t set you back much ($8) and it’s nice to have him return to the place where I found him.