Yet it has a fascination and allure that few other operatic masterpieces have that are structurally more perfect and polished. This masterwork returned to the Metropolitan Opera this past Tuesday in a revival of Bartlett Sher’s 2009 production, a bit of a frustrating puzzle in and of itself. Interest centered on the hot new (to New York) French tenor Benjamin Bernheim, who indeed was the most interesting and effective component in the evening’s success. Hoffmann is a role which the French tenor recently performed successfully in Paris and in Salzburg this summer.

It is a very complete realization of the role with singing, acting, diction, musical style, and stage presence creating a fully embodied and charismatic interpretation of a difficult role. Hoffmann is the connective tissue in all of the disparate “tales” that comprise the work and therefore the protagonist is central to the opera’s success. While the other singers, the conducting and definitely the Sher production seemed at times to be a wayward mixed bag going in different directions, Bernheim maintained a steady focus that provided a compelling central axis to the opera (in itself something of a mixed bag but one of genius).

Bernheim’s voice is lean but brightly focused and blooms at the top. Hoffmann’s vocal writing sits rather high and often centers on or dangerously near the passaggio with high notes popping up out of nowhere. Placido Domingo found the role congenial in his tenor prime because the passaggio was one of the best parts of his dark but idiosyncratically configured tenor. Bernheim’s tone is more vertically laid out with a silvery gleam and sits higher in the French lyric tenor tradition of Vanzo and Clément. He made even the toughest parts of the role sound easy with the voice responding freely from top to bottom. Needless to say, Bernheim’s diction is like cut crystal and his handling of the text incisive and detailed.

If I wanted to be a critical churl and nitpick, I would mention that like most modern international gallic tenors, Bernheim does not feature much in the way of a voix-mixte approach to softer or high-lying lyrical passages like the old school French tenors of yore. Passages like “Ah! Ange du ciel ! Est-ce bien toi?” in Act I or “C’est une chanson d’amour” in Act II were sung with a bright pingy tone that rang out into the house in a more modern international style which sounds less exotic and effete to broader operatic audiences. It would be nice to hear him now and then nod to the grand old gallic vocal tradition.

Tall and slender with angular, unconventional looks, Bernheim projected the image of the tortured, sensitive and emotionally fragile poet who is constantly searching and forever frustrated in life and love only finding refuge in his art. His acting was convincing and free of exaggeration or conventional posturing throughout. Bernheim conveyed real desperation and heartbreak to the finales of each act as each inamorata either eludes, dies or betrays him. This is a neurotic Hoffmann in the Shicoff mold.

As the Four Villains, bass-baritone Christian Van Horn, also Bernheim’s nemeses at Salzburg a few weeks ago, was imposing in voice and physique. It’s definitely a bass-baritone of good size but not dramatic in quality with a rather cantante aspect lacking in boom and snarl (although he tried). I happen to like a suave villain in this opera rather than a booming or barking one – insinuating instead of bullying (Laurent Naouri with much less voice and height showed masterfully how this can be done). Van Horn sang well but loudly most of the time and missed much of the wit in the text. Very tall and handsome, he also seldom attempted physical grotesquerie either as Coppélius or Dr. Miracle. His open-faced bearded visage was the same in each act free of fake noses, painted wrinkles or fright wigs. Paging Samuel Ramey, who was quite the virtuosic stage chameleon master of disguise. Still, Van Horn looked and sounded handsome, has presence and filled out the assignment ably.

Making her Metropolitan Opera debut as Niklausse/Muse was the young Russian mezzo-soprano Vasilisa Berzhanskaya who has scored recent successes at Pesaro, Berlin, Covent Garden and the Wiener Staatsoper. Her timbre somewhat reminded me of the young Vesselina Kasarova in that it has a slightly bottled quality and the registers aren’t always connected and can be incongruent. Kasarova had an individual intensity that drew you in even as the voice threatened to pull apart at the seams (which it eventually did in recent decades). Berzhanskaya also possesses a striking vocal color and has a contralto quality in her lower register. I think a brighter Von Stade sound is more appropriate for this trouser role.

In her first scenes as the Muse and Niklausse in the tavern prologue, Berzhanskaya sounded tentative like she hadn’t completely warmed up. Sometimes high notes would thin out in comparison with the rich middle and bottom. In the first act, her imitation of Olympia’s scales (using her Rossinian coloratura) got appreciative laughs though her “Violin” aria in Act II lacked freedom in the upper register. Her handling of the finale had pathos and authority. I think Berzhanskaya will improve as the run progresses and it’s a distinctive voice I want to hear more of – definitely in bel canto.

Of the three loves, Erin Morley scored again in her third Met run as Olympia. Sounding like a combination of Amelita Galli-Curci and Mado Robin, she decorated each verse of “Les oiseaux dans la charmille” higher and higher eventually hitting an A over high C. Her doll-like movements were precise and funny and the audience ate up all her virtuosic vocal and physical antics. Morley, after Bernheim, gave the best performance of the evening.

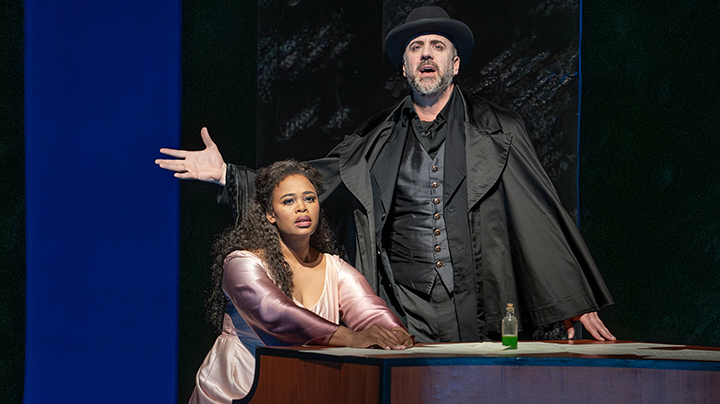

Returning after a five year absence, Pretty Yende played the doomed Antonia in Act II. Yende in recent years has moved away from the high coloratura repertoire exploring demanding lyric roles like Violetta in La Traviata, Magda in La Rondine and the title role in Massenet’s Manon on to agile spinto roles like Lina in Stiffelio, the titular lead in Maria Stuarda and Leonora in Il Trovatore. In Europe, Yende has sung all three heroines in Hoffmann but reports indicate that the stratospheric Olympia is no longer a comfortable fit. Yende always seemed to me a weirdly unfinished singer with a luscious instrument that wasn’t supported by reliable intonation and interpretive insight.

Her performance on Tuesday night also was generally appealing with a larger lyric sound that seemed like it could tackle the occasional higher note or coloratura filigree while filling out in volume for the more strenuous passages like the climactic trio with Dr. Miracle and Antonia’s Mother. In the lyrical passages Yende poured out gorgeous tone while looking and sounding a little too full and healthy — no Malfitano-like consumptive wraith was she. When the music went very high a beat developed in the tone and focus was lost, her one trill was not well-defined.

In the heavy passages, she started to push and her intonation wavered. Mostly it sounded fine, but you never felt she was totally secure. Prior to the pandemic, Yende seemed to be an artist that Peter Gelb was pushing for stardom with HD assignments like La Fille du Régiment and L’Elisir d’Amore – both unnecessary repeats. After the pandemic she disappeared for several seasons and Rosa Feola, Lisette Oropesa (too sporadically), and especially Nadine Sierra rose to prominence in her repertory. It’s still a gorgeous voice that has gained in size but one that isn’t reliable and she isn’t a young newcomer anymore but an experienced international leading soprano. She should be better than she is.

The other native francophone singer in the cast was the Giulietta, Clémentine Margaine, a frequent Met Carmen (she repeated the role in the second cast of the new production last Spring) but in Europe she is a frequent Amneris and Azucena. The voice is huge, especially in the middle, emitting Rita Gorr-like seismic waves of vocal force. In what I have been told is a role debut, Margaine was an imposing and dramatic courtesan – sometimes a bit blunt on the highest notes. The voice still has a plummy wine-colored richness and it was a thrill to hear two native speakers square off in the Hoffmann/Giulietta duet in Act III, though Margaine sometimes could overwhelm Bernheim in volume and breadth of tone. It felt like luxury casting.

The supporting roles were well-taken. Aaron Blake as the various Servants was a joy – this was a stage chameleon – stealing scenes as a supercilious Andres, a spastic goggle-eyed Cochenille, a daffy, grey-wigged Frantz tripping around ditzily with a duster and apron and a vicious sprite of a Pitichinaccio. Blake is more than a character tenor (he sings Tamino among other lyric tenor roles) and is capable of good singing – Frantz’s Act II singing and dancing solo was not a vocal trial but could sound good or bad depending on the situation. Eve Gigliotti as the sinister vision of Antonia’s mother has a good-sized, good quality mezzo voice and Bradley Garvin grieved movingly as Crespel.

Marco Armiliato, the Met’s steady hand in the standard Italian rep, seemed a strange choice for this prototypical French opera. He remains a steady hand in French opera and added a bit of Latin dash and red-blooded energy for what he lacked in elegant gallic finesse. Tempos were fast and forward moving and he maintained a high level of energy throughout. Here or there, ensembles suffered and occasionally volume levels threatened to overwhelm the singers. Again, I think he will smooth over these faults with more performances. Yes, Sir Thomas Beecham or Pierre Monteux he ain’t. For what he is, we should be grateful.

The Met continues to use a musical edition that James Levine concocted for a 1980 Salzburg production that was introduced at the Met in 1982 with the former production by Otto Schenk. It uses the Choudens edition as a general framework but restores the act order to Offenbach’s original intention with the Venice act playing after the Antonia act. Interpolations from the Oeser critical edition add in much extra material for Niklausse/Muse making the character a central leading character who anchors the final ensemble bringing the entire opera into focus musically and thematically. It’s a good solution and I enjoy most of it.

However, the critical edition compiled by Michael Kaye (our late lamented QPF) and Jean-Christophe Keck facilitates casting one soprano as the four heroines (which I prefer and wasn’t done for this revival) and is probably a better solution overall since they found more authentic music for the sketchily reconstructed Venice act (Catherine Malfitano, Carol Vaness and Ruth Ann Swenson, I think, were the only sopranos to take on all four heroines at the Met).

The Bartlett Sher production is busy and all over the place in tone and stage business. Sher said he was inspired by Franz Kafka and Federico Fellini, who have little in common. The visuals go from garish circus decadence to stark German Expressionism with little internal rhyme or reason. Background extras run amok in the Olympia and Venice acts and the tavern scenes. Revival director Gina Lapinski recreated the production with care and detail but some of the details looked messy. The female extras in the Venice act are no longer topless which will help the HD showing (on October 5th) which requires censoring nudity to play certain cinemas. I think that maybe it is time for a fresh look at Hoffmann with a new production and musical edition.

However, for all my critical churlishness and pedantry, I really had a good time on Tuesday night and I urge you to go at least for Chéri BéBé as the poet. And if you can’t get to the Met, try to get to your local movie theater on October 5th for the HD transmission.

Photos: Karen Almond