Singer, actor, activist, first Black student at Rutgers college, Columbia-educated lawyer, NFL player, Communist, enemy of the CIA, and friend of the working class, bass-baritone Paul Robeson stands in a class by himself. If anyone richly deserved the designation of Renaissance man or the operatic-historical treatment, it was Robeson. This weekend at Little Island, Davóne Tines—a Renaissance man himself— brought Robeson back to life in rich, suggestive splashes of color in a recital-cum-opera full of his own arrangements of works associated with Robeson with stellar direction from co-conceiver Zach Winokur.

The performance opened with Tines doing an impression of Robeson’s return to Carnegie Hall in 1958; this was the first time he was allowed to perform in public after enduring years of scrutiny, censorship, and harassment by the state for his political views. A party boat drifted by behind the musicians. Tines, who has one of the most versatile and multifaceted sounds of any artist working today, sounded clear and strong, but it wasn’t fully clear where this was going.

After the third song, however, Robeson began in earnest. Like Robeson did at Carnegie Hall, Tines offered the final monologue from Othello. Othello, a character who works tirelessly to forge his own story in the face of the cruel, insidious narratives that surround him, asks to be remembered accurately, for his awful deeds but also for his triumphs, his nobility, and his dignity. His final tragedy is ceding that story to others. As Tines finished the monologue, the show shifted to give us a premonition of Robeson’s suicide attempt—or, as the singers son believes, an attempt on his life by CIA operatives— in Moscow in 1961. A razorblade slashed Robeson’s wrist. From there we saw Robeson haunted by his own voice, in a deft bit of sound design from Kai Harada, which emanated from a radio and from all four corners of the stage. Robeson’s voice was suddenly no longer his own. The updated mad scene might seem gratuitous to some, but to me it cemented the strength of Tines and Winokur’s project; they might have meant to shock us, but this scene was so laden with meanings, the traumas endured by Robeson so layered, that it still managed to feel complex.

Musicians John Bitoy and Khari Lucas, who up to this point had provided sterling accompaniment hadn’t gotten to flex their muscles fully, began to shift the sound-world from the standard piano-voice into a new space of electronics, guitar, and drums, with pre-recorded tracks joining Tines in key moments. It was slick and richly textured, adding texture and dimension that only grew after the show.

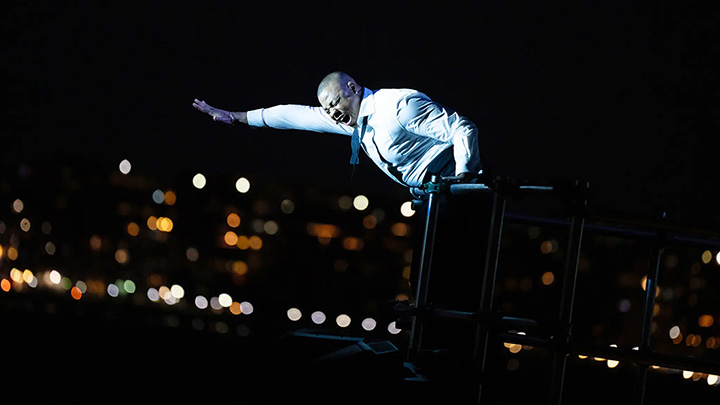

Tines here was mesmerizing, singing a rendition of “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” that firmly cleared it from all cobwebs of cliché. Soon after, he launched in the gospel standard, “Fly Away.” Breaking free from his Robeson impression, Tines’s voice climbed higher and higher in a cry of rage and longing, as he climbed a balcony and stretched his arm out over the Hudson. It was searing, visceral, and sung with impeccable control.

While the central scene was almost overwhelming in its intensity and power, and it’s clear that Robeson had a lot to say—about singing as a fight for justice, about what it means to have a voice— for the most part Tines allowed the musical selections and his own vocal prowess to speak loudest.

This light-handed touch with exposition showed both a deep respect for Tines’s historical interlocutor and a trust in the intelligence of his audience. Instead of being told about Robeson, we saw something of Robeson. From “This is the Hammer,” we see Robeson as a champion of the working man. From “The House I Live In” we get a glimpse into the singer’s tortured relationship with America: both his anger and betrayal at the injustice at its core and the love for the people who built it on their backs. From “The Volga Boat Song” we understand a bit about his interest in Russia, to which he retreated at various times.

And in turn, we saw something of Tines, who came across not only as a singer at the top of the vocal game, but a brilliant researcher and reader of literature, drama, and history, and an artist with real vision.

Near the end of the concert, Tines sang a version of “This Little Light of Mine” that took the Sunday-school classic and forged it into something blistering and white-hot; it traveled from the deepest bass to the heights of glory, as Tines’s upper range nearly to burst into flames. It was so spectacular that tears sprang into my eyes from the pure thrill of the singing. There was a mid-song ovation from the assembled crowd, and a small smile crept over Tines’s face. He had us, and he knew it.

Everything we’d just heard, Tines told us, was something Paul Robeson sang or said, or something that was said about him. The night ended with a new version of “Old Man River” a beloved song from a racist musical that Robeson—according to Tines—struggled throughout his career to adapt into something true, even liberatory. Tines described his frustrations with the song, and then, in his most moving tribute to Robeson yet, Tines offered his own adaptation (“there’s that old man I *don’t* want to be”), one where that river symbolizes the relentless tide of violence, censorship, and resignation, against which the singer stood firm as a boulder, unmoved by the eddies.

Photos: Julieta Cervantes