While such a bold life motto may have been embraced by many artists today, it was almost unthinkable for a musician in the seventies, let alone for a contemporary classical (specifically, minimalist) composer. Thus was the case of Julius Eastman, whose powerful Femenine graced three Bay Area concert halls in a spectacular fashion — Bing Concert Hall at Stanford on February 10 (as part of two-day residency), Green Music Center in Sonoma on March 8, and last Saturday at Zellerbach Playhouse in Berkeley (the performance in review) — courtesy of Los Angeles-based contemporary music ensemble Wild Up and conducted by Christopher Rountree.

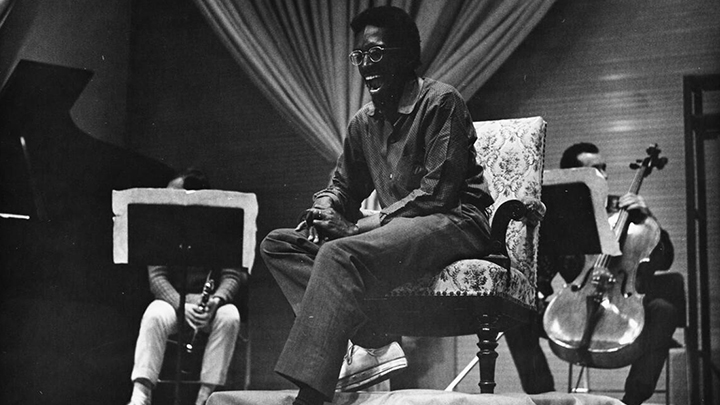

The multi-hyphenate Eastman – composer, pianist, vocalist, and performance artist – was undoubtedly an enigma. Born in Manhattan in 1940, he studied piano with Mieczys?aw Horszowski and composition with Constant Vauclainat Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia and graduated in 1963. He became a member of the Creative Associates program at University of Buffalo (which performed many of Eastman’s early works), joined Petr Kotik‘s S.E.M. Ensemble, and collaborated with the likes of Pierre Boulez and Meredith Monk. After moving back to New York City in the late seventies, his life began spiraling out of control and he eventually lost most of his belongings (probably including his scores and recordings) during an eviction. Eastman died alone at the age of 49 of cardiac arrest in Buffalo in 1990 after spending most of a decade homeless.

Eastman’s legacy was carried on by the herculean efforts of his friends and scholars, especially by the composer Mary Jane Leach, who, along with musicologist Renée Levine Packer, edited a biography on Eastman in 2015 titled Gay Guerrilla: Julius Eastman and His Music, named after one of Eastman’s well-known works. Musicologist Kerry O’Brien chronicled those painstaking efforts (by Leach and others) in her article for Chicago Reader, which culminated with the 2016 release of S.E.M. Ensemble’s live recording of Femenine with Eastman himself in piano, captured on November 6, 1974 in Albany (the whole recording can be heard here). Both the book and the recording spearheaded a surging interest in Eastman’s life, and particularly, compositions; the man wasn’t just a myth anymore!

With his provocative, brilliant, and radical persona, it is little wonder that Eastman continues to inspire a new generation of musicians. One such devotee is Wild Up. Founded by Rountree in 2010, Wild Up aims to (according to the program notes) “eschew outdated ensemble and concert traditions by experimenting with different methodologies, approaches, and contexts.” In 2021, Wild Up launched Julius Eastman Anthology, a planned seven-volume recording project (with New Amsterdam Records) and a series of performances, dialogues, and public programs as “a portrait and response to one of our favorite composers”. The first three volume had been released: Femenine (June 2021), Joy Boy (June 2022) and If You’re So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich? (June 2023).

Musically, Eastman’s style was deeply rooted in minimalism; his works often included significant amounts of repetitions and aleatory/improvisational music, even incorporating elements of pop music. He called it “organic music;” O’Brien above defined it to be “a style of gradual accrual and accumulation, often followed by gradual disintegration.” Eastman also fully embodied the motto “to the fullest” at the beginning, including controversially naming some of his pieces with the most offensive slurs to raise questions about racism and homophobia — and he was consciously ready to defend those decisions.

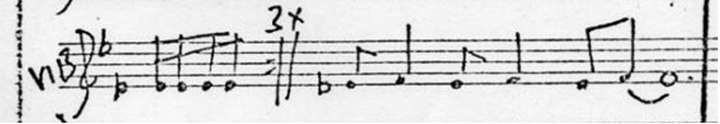

All those qualities could be found in Femenine, a sprawling 70-75 minutes piece with only five pages of manuscripts. Composed in 1974 as a companion piece to Masculine (now thought to be completely lost), it was scored for winds, marimba/vibraphone, sleigh bells, piano, and bass (note the quirky spelling of the word). The sleigh bells played before, during, and after the piece, completely envelope the score and give it a wintry outlook (the 1974 recording used mechanical sleigh bells). Upon this landscape, a two-note theme below appeared in the vibraphone repetitively – called the Prime – before the other instruments chimed in, sometimes to enforce the Prime, other times to counter it. The score above only gave indications about the timing for the changes without any details of each part.

With such a loosely defined structure, no two performances of Femenine could ever be the same, and in a way, it turned out to be alluring to a lot of contemporary ensembles as it provided a short of blank canvas for the ensemble to shine. Rountree described it best in his 2021 interview: “The biggest liberty is the inclusion of a dozen or so long solos — all at architecturally significant moments in the piece. Most classical players don’t grow up improvising, but most of the players in Wild Up are composers and improvisers as well.”

It’s no small wonder that a number of recordings started to come up following the release of 1974 live recording; Wild Up’s 2021 recording was actually the third release of Femenine (not counting the 1974 version) as it followed 2019 release by ensemble Apartment House (on Another Timbre) and 2020 version by ensemble 0 and Aum Grand Ensemble (on Sub Rosa). New York Times critic Zachary Woolfe, in his detailed review of Wild Up’s recording, compared the 4 recordings and gave links for each to sample. The fifth recording came out just last year by Talea Ensemble and Harlem Chamber Players (on Kairos).

Wild Up’s production itself emerged from an earlier 2018 performance of the piece by Echoi Ensemble which featured some of the principals of Wild Up and can be seen entirely below.

Personally, Wild Up’s 2021 recording had the added advantage of being the only recording (so far) that had the music being broken into 10 different “sections”, all of which were signaled in the score. It helped significantly to gain understanding of the structure of the piece and, in turn, brought a new appreciation of Eastman’s organic music. Wild Up also launched into hymn “Be Thou My Vision” on piano (during the portion marked “Mao Melodies” in the score) there, taking a cue from Eastman’s own 1974 recording.

In true Eastman’s fashion, last Saturday performance presented different composition of instruments than the recording, with 2 violins, viola, cello, bass, 3 flutes, 3 saxophones, 2 percussions, piano and 2 singers, plus several members (uncredited) on various types of bells scattered around the hall. The stage was pretty much bare, with only a gold backdrop and the instruments arranged in a semi-circular position facing the audience (except for the grand piano/electronic keyboard and the conductor’s chair).

Despite the setting, there was a sense of theatricality with Wild Up’s presentation, ritual even. When the (sleigh) bells started, the stage was completely empty, resulting in the audience looking around to find the source of the sounds. Percussionist Sydney Hopson then entered the stage, stylishly whipped out his phone, took his spot and began the Prime motif that commenced the whole proceeding. One by one, the instrumentalists entered the stage, whipped out their phones, took their spots and began playing their parts. Interestingly, they also left the stage when they were not playing, resulting in the constant movements of players in and out of stage throughout the whole piece. In a way, the stage turned into something akin to shared workspace favored by many tech companies, where people came into a desk to work and left afterwards. Personally, I felt that the movements were a little bit distracting, especially because there were times when the players leaving the stage were walking in front of their colleagues giving a solo! Curiously, Rountree spent very little time on stage, as he only appeared for a short period in the beginning (after all the players were in) and towards the end of the piece.

Clad in all-black ensemble adorned with black harness and black leather shoes, pianist Richard Valitutto made a striking impression, no doubt in a nod to Eastman’s status as virtuosic queer pianist. He spent some time in the beginning tinkering with the strings of the grand piano, creating an ethereal sound from the instrument. He was also using both the grand piano and the electric keyboard interchangeably, some time even for just a single note. Valitutto’s piano shifted gradually from the soft sound in the beginning to increasingly thunderous and commanding, particularly in the second half, where he literally banged the piano with block chords (no wonder Eastman wrote “pianist will interrupt must return” in the score!) I was particularly mesmerized by his entry into “Be Thou My Vision;” right at the climax, where everybody was playing at their loudest, he came in softly but determinedly to bring everybody to the church!

Wild Up truly consisted of extremely talented musicians, and the improvisational nature of the score generated continuous shift of moods throughout the piece (depending on whoever played the solos) in a totally unpredictable way, even under the constraints of the Prime theme. While to my ears the music sounded a lot like gamelan most of the time (because of its percussive nature), especially in the central “E Flat” section, the saxophone and bass solos transported me to a jazz club, the flutes to Brazilian tropical forest, and the violin solo to a European concert hall. The Ivesian gospel nature of the “Mao Melodies” (how ironic was that!) was charming, but the voices (by Mingjia Chenand Odeya Nini) were particularly wild, ranging from chirping birds to listening to neighbors having sex! It was truly easy for the audience to just let go and be taken to places by the piece. The piece ended with a reversal of the opening scene; after a heartbreak duet with Mia Barcia Colombo’s cello, Hopson was the last man standing, and he played the Prime motif in decreasingly quiet nature (the final one was barely audible) as if to justify O’Brien’s description of “organic music” above. The bells then finally rested.

I was originally disappointed that Cal Performances didn’t provide a description of the piece in the program notes, but after listening to it, I could understand why. There was no certain way to describe the experience perfectly, especially since there was no authoritative way to present it! On a final note, amplification was used for all instruments, and to these ears they sounded fine and clear (but I was sitting right in front of the orchestra!).

It was truly electrifying to experience this piece live, and it really warmed my heart to see the level of dedication and passion Wild Up brought to raise awareness of Eastman’s oeuvre and to carry his music and ideas forward. It certainly triggered my own personal exploration of his compositions (and not just because the Prime theme had been stuck in my head!) I’m certainly looking forward to the next releases of Wild Up’s Julius Eastman Anthology. Last but certainly not least, these tours of Femenine were not their last words on the piece, as next year they are going to premiere a new immersive installation staging of Femenine in a collaboration with artists and choreographers Gerard & Kelly, a co-production of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philharmonie de Paris, La Villette, and Festival d’Automne a? Paris.

Comments