httpvh://youtu.be/iT4nC9FncCg

In 1938, Italy produced a dramatic film version which sadly seems to be lost. The work disappeared after WWII though occasionally regional revivals in Italy emerged providing private recordings. It was broadcast by RAI in 1977, revived in Wexford in 1979, at the San Carlo in Naples in 1984 and a 2013 stage production at the Festival della Valle d’Itria produced a DVD released on the Dynamic label.

Joan Sutherland, inspired by Tetrazzini, recorded “I non sono più l’Annetta” and programmed it as an encore in her recitals and for television appearances.

httpvh://youtu.be/0fhBL_udEcA

The libretto by Francesco Maria Piave (described as “Fantastico-Giocoso”) concerns a penniless cobbler in Venice, Crispino, and his wife Annetta, an unsuccessful vendor of sheet music and pamphlets. The rent is due and the miserly rich landlord, Don Asdrubale, tries to make a sordid deal with the pretty Annetta who refuses his attentions.

A despondent Crispino decides to throw himself into a local well from which emerges the mysterious Comare (Fairy). This capricious fairy offers to make him a rich, successful doctor to humiliate the various local quacks including the sharp Fabrizio and the incompetent Mirabolano. The fairy will appear when a patient is to die but won’t if the patient will live. Crispino is then able to accurately predict the outcome and prescribe food and wine to the patients that will live – who do so.

Crispino’s wealth and prestige go to his head and he becomes arrogant and dissolute. The Fairy gives him a taste of his own medicine in Act III by dragging him down to the underworld showing him his own death and final judgment.

There is a subplot concerning Don Asdrubale’s lovesick heiress ward and her aristocratic but thwarted suitor (shades of Il Barbiere di Siviglia) which is solved when the Comare predicts a fatal heart attack which Crispino is able to diagnose to the minute.

The music is delightful with strong echoes of Don Pasquale and Rossini’s opere buffe including Il Cambiale di Matrimonio. The contralto Comare seems a spiritual and vocal sister to the conniving Mrs. Quickly in Verdi’s Falstaff (Verdi admired the Ricci Brothers and this opera). The work has sung recitatives accompanied by the orchestra and fortepiano though it is a cousin to Italian operetta with the numbers having a strong Italian canzone popular song flavor. Annetta has several waltz-like solos besides the familiar “Io non sono più l’Annetta”.

The most musically striking section is a very long trio for bassi buffi in Act III that is like Don Pasquale’s “Cheti, cheti, immantinente” for three voices. The Ricci Brothers are not great innovators in operatic style or form but are working within the best traditions of Italian comic opera. Verdi himself praised them for their “good themes” and the melodic invention is consistently high throughout the work.

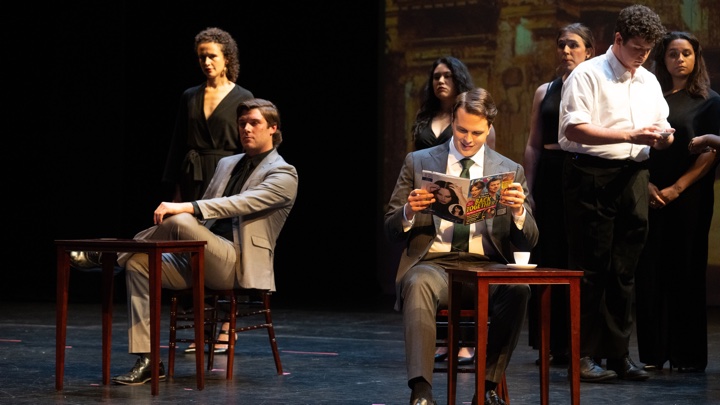

The Teatro Nuovo production was semi-staged with colorful projections of vintage set designs for the opera giving the illusion of a full production. There were a few props and costume changes for the main characters. It felt fully realized and not like a concert presentation.

The orchestra (on classical period instruments) was in consistently bright and sharp form led by Jonathan Brandani on the fortepiano. Italian-born Brandani, currently the Artistic Director of the Calgary Opera, is an experienced and talented conductor who kept everyone together and on their toes. He is a bright, still-young talent who needs to be utilized locally.

The revelation of the cast was Brescia born Italian bass-baritone Mattia Venni as Crispino. He proved a total stage animal, acting the role with his whole body with great spontaneity and comedic verve. His native facility with Italian scored comedic points throughout the evening . His interpretation was directed more towards wit and satire rather than buffoonish clowning. His lean bass-baritone is pithy and nimble.

As his vivacious coloratura wife, Teresa Castillo was in healthy sparkling voice and balanced earthy sexiness with mischievous sparkle. Annetta loves to flirt and enjoys the good life but also has morals and takes no nonsense from men including her husband. Castillo crowned the evening with an interpolated finale: Luigi Venzano’s grande walzer per coloratura “Ah! che assorta” minus the de rigueur final crowning acuto.

httpvh://youtu.be/hUxUy1pJAjs

Mezzo Liz Culpepper displayed a plummy sonority and sense of fun onstage as the mysterious Comare. Bass-baritone Dorian McCall revealed a distinctive, slightly nasal timbre and lots of personality as the streetwise Dr. Fabrizio. Lyric tenor Toby Bradford made a nice impression in Contino del Fiore’s Act I romanza.

Bass Vincent Graña, as Mirabolano and the handsome baritone Scott Hetz Clark (an incongruously young and barihunky Don Asdrubale) were very much in the picture with less striking instruments. Abigail Lysinger as Lisetta and Jeremy Luis Lopez as Bortolo in minor roles filled out the supporting cast adroitly.

What was evident is that these young singers were all working as an ensemble, each knew what they were doing, what they were singing about and why. Well coached in the style and working off of each other, the whole cast was greater than the sum of the parts.

The audience got to enjoy a delightful lost jewel that filled in what Italian comic opera was up to between Don Pasquale (1843) and Falstaff (1893). The world of 19th and early 20th century Italian operetta is another lost continent full of hidden treasures in need of a musical explorer’s discovery.

Photos by Steven Pisano (c) 2023