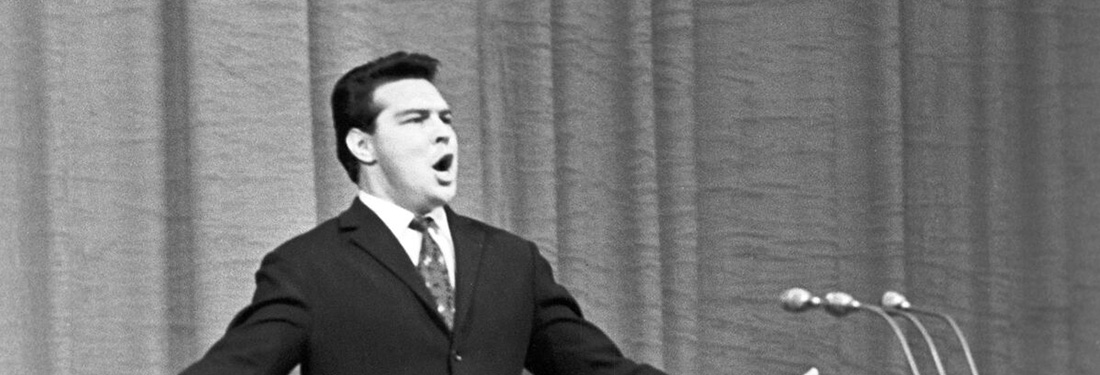

Since I first heard MariAnne Häggander’s rendition on a great BIS CD I bought in the late 1980s, I’ve longed to hear Jean Sibelius’s Luonnotar in person. I therefore had to attend the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s guest appearance at Carnegie Hall on April 25 when Andris Nelsons led a luminous Golda Schultz in the striking 10-minute tone poem for soprano and orchestra.

I was surprised to read that the work’s first Carnegie performance in 1955 was given by Jennie Tourel. I haven’t run across any other mezzos taking on its high tessitura; one of my favorite versions (by a singer I usually don’t much care for) is by soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. Luonnotar has often been favored by Scandinavian divas like Soile Isokoski, Karita Mattila and, lately, Lise Davidsen whose powerful recent performances differ greatly from Schultz’s.

Rising to the challenge of Sibelius’s mysterious mythic monologue, Schultz, whose delicately radiant soprano has lately been embracing heavier operatic repertoire like Donna Anna, Lidoine and Agathe, had no difficulty soaring over Nelsons’s seething orchestra. More than some other versions I’ve heard, Schultz took an intently narrative approach with crisply delivered the text.

It seemed strange to open a program with Luonnotar but Nelsons concluded the evening with another Sibelius work, his Fifth Symphony. In between Anne-Sophie Mutter fiddled through a new Thomas Adès she recently premiered and Mozart’s slight first violin concerto which she unbalanced with three unnecessarily elaborate and showy cadenzas.

The next evening, Les Arts Florissants, absent from New York since early 2019, returned with another chapter in its seriously consequential revival of the oeuvre of Marc-Antoine Charpentier. The first LAF concert I attended after moving here was a 1991 all-Charpentier bash at the Brooklyn Academy of Music featuring the Te Deum, his most famous work.

My first in-person encounter with favorites Sandrine Piau and Mark Padmore, the concert also included the exquisite Missa Assumpta est Maria. That evening was followed over the years by LAF performances of Actéon, Médée, as well as other sacred works like his Leçons de Ténèbres, but never Les Arts Florissants, the brief Charpentier opera that lent its name to William Christie’s group.

Wednesday’s Zankel appearance arrived a few weeks late with four Holy Week pieces by the late 17th century master. Performing without a break, the nine male singers and eight instrumentalists wove a hypnotic spell. Though they performed with the impeccable polish one expects from Christie (in charge at the organ), there was little variety to the darkly solemn works. I’ve listened to a great many of Charpentier’s sacred works (H. Wiley Hitchcock’s catalogue lists over 400) and Christie’s choices this time didn’t strike me as especially inspired.

The two extended solo works performed by a pair of able if unexciting basses only added to the heaviness. The opening Méditations pour le Caréme accompanied by continuo only contained ten brief motets each with swathes of Latin text it was impossible to follow in the darkened theater. The concluding Troisième Leçon ud Vendredi H. 137, a more compact piece with strings and recorders proved the most satisfying, and the voices at times joined together thrillingly.

While it was great to hear LAF again, I was reminded of a more varied Charpentier concert the group led by Paul Agnew performed here six years ago: beautiful but ultimately a little wearying.

I wished Carnegie had instead imported a program LAF performed a few weeks ago in which Véronique Gens and Lea Desandre parried in arias and duets by Gluck and Mozart.

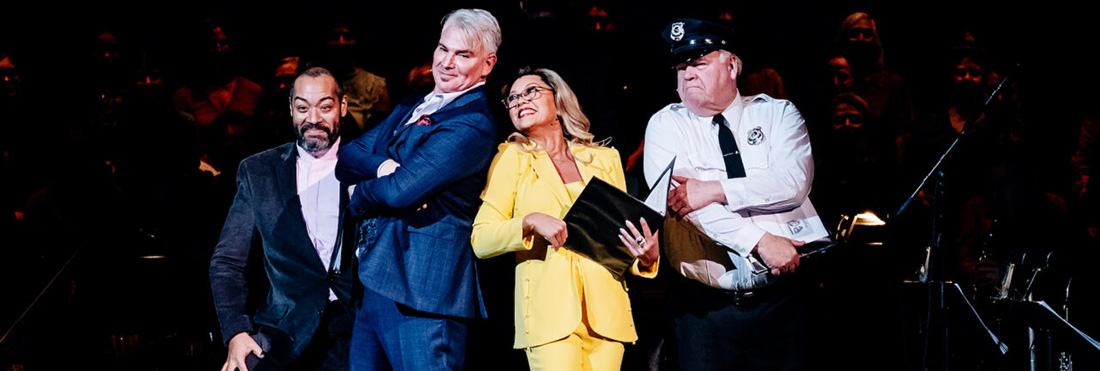

On Thursday, the Park Avenue Armory’s excellent recital series which hosted Michael Spyres in September presented Allan Clayton, another special tenor, in his North American recital debut. Best known in the US for his recent Met appearances in the title roles of Brett Dean’s Hamlet and Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes, he and his marvelous pianist James Baillieu opened their concert in the intimate restored Board of Officers with the Kerner Lieder, one of Schumann’s lesser-known cycles, followed after intermission by a batch of songs by four gay (coincidentally?) composers: Britten, Priaulx Rainier, Nico Muhly and Michael Tippett.

The melancholy 12-song Schumann set found Clayton in fine form although his intent gaze at the score on the music stand before him was frequently off-putting. The tenor who is such a kinetic performer on the operatic stage seemed oddly constrained as “himself.” His arms rested by his side for nearly the entire concert; he gestured just twice toward the very end. If I’d closed my eyes, I would have experienced a vividly moving Schumann cycle with a magnificently expansive “Stille tränen” as its high point. But—eyes wide open—the experience was a bit diluted.

The English-language collection began with the first Britten Canticle “My beloved is mine and I am his,” a touching work dedicated to Peter Pears. Clayton beautifully negotiated the work’s gently lovely lyricism. The starkly titled Cycle for Declamation by the South African Rainier (written for Pears) called for unaccompanied stentorian address; it was illuminating to hear these experiments by a near-forgotten composer, but I don’t think I need to hear them again, The same might also be said for Tippett’s arid Songs for Ariel, a troika written for a 1962 production of The Tempest.

The evening’s surprise was Muhly’s gorgeous The Map of the World. While I’ve enjoyed Muhly’s choral works, his compositions for solo voice have left me wanting more: not so his setting of Chaucer which was done with tenderest emotion by Clayton. Four of Britten’s Folksong Arrangements concluded the evening and found the tenor in more relaxed form finally letting loose for a witty “The Crocodile.” As so often, the encores proved especially satisfying: an ardent Liszt song was followed Britten’s “Deaf Woman’s Courtship,” a riotous duet between Baillieu and Clayton who adopted a deliciously campy high falsetto.

The Armory’s recital series will return in September with Julia Bullock followed by one of the fall’s premium events: Jonas Kaufmann in a Claus Guth-directed staging of Schubert’s Schwanengesang. Baillieu reappears locally that same month accompanying Davidsen in her recital at the Met.

After that filling trio of concerts, I sought out two films I’ve been curious about at local cinemas: Chevalier, a leaden if lusty biopic about Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, a fascinating 18th century mixed-race composer…

…and choreographer Benjamin Millepied’s ravishing but unfocused Carmen whose purported resemblance to Bizet’s opera is nearly undetectable, though I spied Prosper Mérimée’s name in the credits.

I enjoyed Carmen more than Chevalier, whose creators surely watched a lot of Bridgerton. Charismatic American actor Kelvin Williams, Jr. as Boulogne struggles with his accent because of course every French character must speak the King’s English. The blandly pretty actresses playing Boulogne’s love interest and Marie Antoinette had no chance opposite Minnie Driver’s delicious scenery-chewing as La Guimard, one of the ballerinas who foiled the composer’s doomed scheme to run the Paris Opéra.

Though Millepied never quite decided what Carmen should be, he wisely hired cinematographer Jörg Widmer and composer Nicholas Britell who are responsible for the gorgeous look and sound of the film. Though she dances well, Melissa Barrera’s shallow Carmen leaves a hole at the center of the film that even jacked and tatted-up Paul Mescal’s magnetic marine-on-the-run can’t entirely rescue. However, this portrayal along with his achingly vulnerable lost dad in Aftersun mark the English actor as a star on the rise.

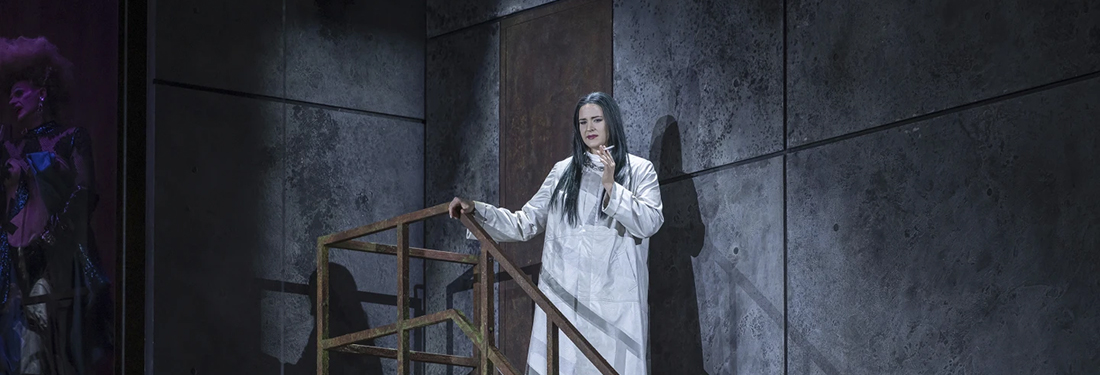

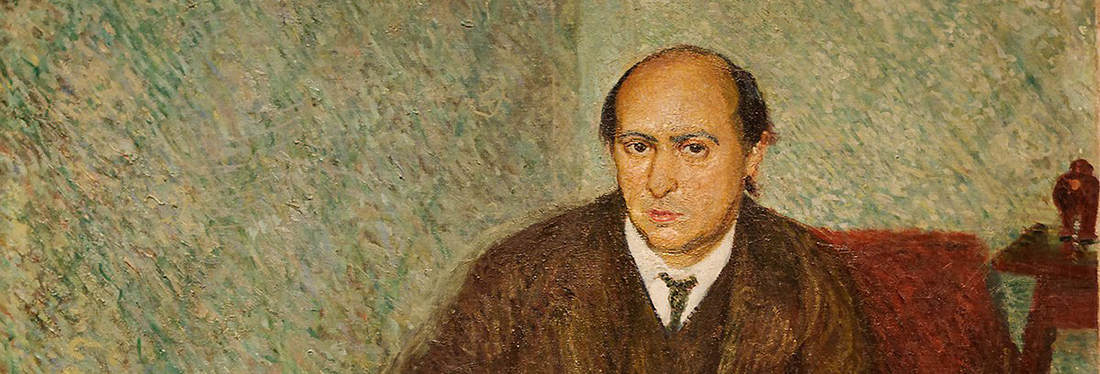

At home I aslo caught Il Boemo, the second recent biopic of a rakish 18th century composer, in this case, Josef Myslivecek. Born in Prague, he had a brief but enormously successful career writing opera seria in Italy. According to the handsomely designed and photographed movie which features several nicely recreated opera scenes, he bedded even more unavailable married women than Boulogne before grossly disfiguring syphilis killed him at 43.

Despite some female nudity and a tepid orgy, Il Boemo is a more serious enterprise than Chevalier. While nearly all of the film is in Italian, dashing Vojtéch Dyk gets to play a scene in Czech in which he becomes both the composer and his identical twin brother!

Warner had announced plans to release a soundtrack CD featuring Emöke Baràth, Raffaella Milanesi and Philippe Jaroussky, but it has yet to appear.

An annex edition of Chris’s Cache to accompany this review includes Golda singing Luonnotar on a broadcast from an earlier April BSO concert, Charpentier’s Troisième Leçon ud Vendredi H. 137 from an identical LAF concert in Gdansk; as Clayton stars in a new production of Handel’s Jephtha at Covent Garden next season, a preview with “Waft her angels;” Mutter played one of Saint-Georges’s violin concerti earlier this year at Carnegie, plus Vivica Genaux sings an aria from Myslivecek’s La Calliroe at a 2011 Prague concert with Collegium 1730 under Vaclav Luks.

Photos: Fadi Kheir (Schultz); Da Ping Luo (Clayton)

Comments