There are predictable complaints about the damsel-in-distress stories. But even more, what I hear is that it’s the musical style and structure—something about the frequent use of cavatinas (to demonstrate legato) and cabalettas (to showcase virtuosity)—that pulls my theater friends out of the moment.

I thought about this watching and listening to Rossini’s Otello, the centerpiece of Opera Philadelphia’s Festival O22. It’s a show that I think offers a fascinating blend of pros-and-cons that could provide supporting evidence to both camps.

Before I get into the details, for those of you who want a basic “should-I-go?” recommendation, it’s an emphatic yes. A consistently strong cast deliver on all cylinders, with a few singers—Lawrence Brownlee and Daniela Mack in particular—bringing a Golden Age combination of musicality, tonal beauty, and coloratura fireworks that is literally jaw-dropping.

And now for the less good news. Frankly, a lot of it starts with Rossini. His mastery of comedy is, of course, taken as a given; but a number of revivals of his less frequently performed dramatic works—Semiramide in particular—have made a case for them as reasonably effective theater.

Alas, I can’t say the same here for Otello. It certainly doesn’t help that we have Shakespeare and Verdi to compare this to, but, even on its own, Rossini’s Otello strikes me as somehow managing to reduce a sure-fire plot to meandering silliness (libretto by Franceso Maria Berio), and offering in its place a parade of anything-you-can-do vocal opportunities.

I’ve long thought that Rossini’s predilection for hyperextended preludes and postludes framing musical numbers is an unsolvable problem for even the most imaginative directors. And at least in Otello, the arias and ensembles themselves can be exciting—but rarely do feel they are in the service of the story. (Desdemona’s “Assisa a’ pie d’un salice,” a ravishing piece with harp accompaniment, is a shining counterexample—but there’s nothing else here at that level.)

Indeed, the composer was noted for his frequent repurposing of his own material. Those familiar with his canon will likely recognize here that the cabaletta to Rodrigo’s anguished second act aria, “Che ascolto? Ahime, che dici?” is the same melody heard in the mischievous “Duetto buffo di due gatti.” So much for narrative specificity!

I wish I could say the O22 production addresses the dramatic problems, but too often it exacerbates them. The piece is updated to what I take to be late 19th century. In itself, that’s not a problem; Othello can work in any number of historical settings. But the entire milieu here makes no sense. The play is rough-edged, exotic, tinged with underlying military prehistory (modern audiences will likely intuit the concept of PTSD). References to “the Moor” and Africa abound.

So why here does the elegant and lovely visual world evoke, of all things, Downton Abbey or Gosford Park?

It’s certainly handsome to look at—the next time I redecorate my Cotswolds manor, I’ll call the design team—but that’s hardly the point. Further diluting the sense of theatricality, the direction here focuses on creating balanced, pretty pictures that often fight the dramatic arc. It makes no sense at all to have Desdemona and Emilia in intimate conversation across a balustrade and a staircase… or that large numbers of onlookers sit down at the height of a tense moment. But that’s what happens.

In other words, there’s quite a bit here to give ammunition to my anti-bel canto friends. But not so fast… because then, there’s the singing.

I’ve long tried to make the point about this kind of work that you have to make a paradigm shift, and look to the music making as the drama. If you’re willing and able to that, O22’s Otello pays off thrillingly. Given the difficulty of every role here, the high consistency of the cast is a marvel, all of them possessing the requisite rock-sold technique needed for both the lyrical and showy demands.

Underpinning all of this, conductor Corrado Rovaris and the orchestra provide idiomatic support, though a few solo passages sounded a bit scrappy at the first performance.

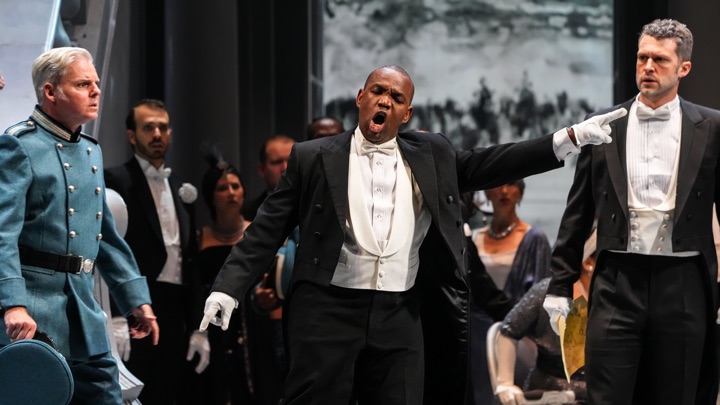

It will likely surprise those who don’t know Rossini’s opera that the title character—a tenor—is actually less prominent than two other tenor parts, Iago and especially Rodrigo. In Act I, he seems almost like a supporting character, though his presence becomes far more prominent in Act II. Khanyiso Gwenxane, making his Opera Philadelphia debut as Otello, rises to the challenge there, and throughout cuts a credible, multi-faceted character. His lovely voice is a bit too lyrical for this part, but his mastery of the line is considerable.

Alek Shrader (Iago) is another compelling stage actor, and the baritonal color of his tenor really suits this material. Shrader also consistently made the most of the words, and dispatched the florid work with ease.

Similarly, bass-baritone Christian Pursell (Elmiro) had both tonal beauty and exceptional fluency in the runs, and he too is a galvanizing presence. In smaller but key roles, Colin Doyle, Aaron Crouch, Daniel Taylor all impressed. Sun-Ly Pierce (Emilia) is a major find—her distinctive and beautiful mezzo soprano made every moment count, and she’s fine actor.

Even in this august company, as I mentioned at the beginning, two performers stood out beyond the others. Daniella Mack (Desdemona) is a riveting presence who knows the value of focus and stillness. To watch her is to feel that she’s fully immersed in the scene. As for the singing, whether in florid work (always cleanly articulated but also bound into a legato phrase) or cantilena, the voice pours out like molten gold. We are fortunate to live in a time of sensational mezzos, and Mack is in the top tier.

As for Lawrence Brownlee… well, I was present in 2001 when he won the Met auditions, and also in 2007 when he made his formal debut in Il Barbiere di Siviglia. Both were unforgettable evenings. Even more astonishing, his voice retains the freshness, suppleness, and clarion top notes that electrified me 20-plus years ago.

Rodrigo is ball-breaking role, but Brownlee makes the demands sound easy—tossing in additional high notes and audaciously decorating cabalettas as if it were the easiest thing in the world. Yet even with all this technical command, for me it’s the plangent and very individual beauty of the sound that makes the deepest impression.

Last night, I wanted my theater friends to be hearing what I was hearing. I think they would have understood that this is why bel canto works. It’s music and it’s theater. And it’s glorious.

Photos by Stephen Pisano

Comments