All the elements of what made Sondheim the 20th century’s pre-eminent musical composer is here, but simultaneously underthought and over-eager to impress. MasterVoices, then, under the energetic direction of Ted Sperling, had a considerable task on their hands in elevating this material that combines the very worst of both 1960s idealism and cynicism.

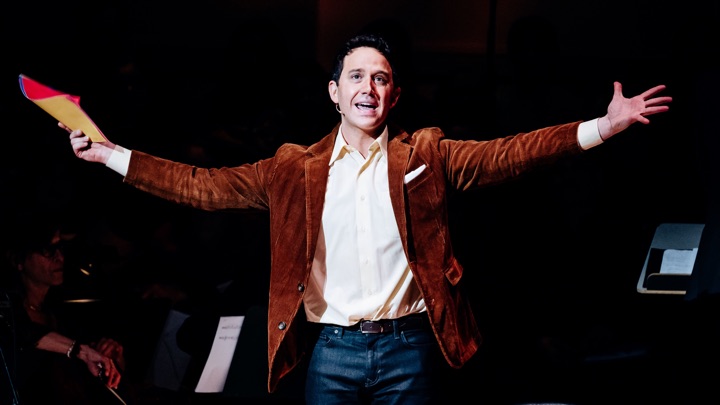

The brightest spot of the evening was Santino Fontana, who shot to international fame with his role in Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. Mr. Fontana excelled in this uneven role, a perfect Sondheim agent of chaos, combining a sleek, breezy vocality with deliberate movement and subtle comedy. He was truly a pleasure to watch, the only person who always seemed completely at ease on stage. Both his duets with Fay (Elizabeth Stanley) were highlights of the whole production, bringing liveliness and clarity to the evening.

Mr. Sperling clearly—if incomprehensibly to me—loves this material with the passionate devotion of a true believer. He led the large orchestra with panache, even if they didn’t always match his energy.

Johanna Gleason, one of the most beloved Sondheim interpreters alive, felt utterly wasted as the narrator; everything that made her performance Baker’s Wife iconic—that dazzling combination of profoundly human frailty, earthy voice, and a sardonic air—was unable to appear here. This bit of stunt casting is part of the tradition of Anyone Can Whistle’s concert history. She didn’t have that much to do, and the narration itself doesn’t give her much to work with. It would never have happened, but I wish I could have heard her sing.

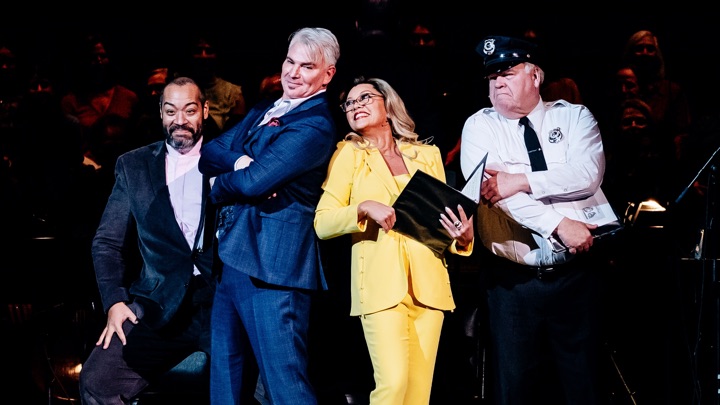

The trio of evil mayoress Cora Hoover Hooper’s lackeys, Schub, Macgruder, and Cooley (Douglas Sills, Michael Mulheren and Eddie Cooper, respectively), had little to sing and not that much more to do. Sills as Comptroller Schub showed a knack for comic timing, even his jokes were never particularly funny, but seemed to struggle with picking an accent, his voice and manner changing wildly from scene to scene.

Vanessa Williams, one of Broadway and television’s most fabulous divas, felt a little dulled in this performance. Her first number, “Me and My Town,” was exciting and polished, her cool, smooth voice adding a surprisingly intimate and human feel to Cora Hoover Hooper. Done up in a glorious pink jumpsuit and backed by delightfully scene-stealing dancers, Ms. Williams was obviously channeling Marilyn Monroe, to charming effect.

However, as the show wore on, Ms. Williams voice and acting lost a bit of their sheen, with more numbers sung from the book, more struggles with high notes, and less specificity of character.

Elizabeth Stanley, whom I thoroughly enjoyed in Jagged Little Pill a few years ago, was cursed here with one of Sondheim’s most insufferable women characters and one of his least developed: Fay Apple. What does Fay want exactly? She wants a hero? She wants to cure her patients, but also make sure they stay her patients? She’s a “woman of science,” whatever that means? She is wildly under characterized, so Ms. Stanley was fighting an uphill battle.

When in her French disguise, Stanley brought life and verve that I missed a soon as it was gone. Fay herself never really came together for me; Stanley sang her final two solo numbers marvelously, particularly “See What It Gets You,” showing command, intelligence and sterling belt. Finally, we saw a real Broadway star. It’s too bad that when the music was over, Fay flattened again into her usual vagueness.

The only duet between Williams and Stanley—which strikes me as egregiously sexist today as it contains none of wit and generosity extended to the rest of Sondheim’s female characters—felt tired and vaguely embarrassing. I would hate to sing it myself, given that it’s basically just catty girl-on-girl bullying. It reifies plenty of misogynist canards without offering a single intelligent critique of them, as if putting them in the mouths of women makes them clever.

Here, I believe a little less reverence for the material would have been helpful; we needed a wink here, something to say “we know this is crazy, but just go with us.” Sondheim’s general genius is not in dispute, but this show has stayed largely in the vault for a reason. If a performance is to become more than just a museum piece, worthwhile not because of its own merits but because of its status as a predecessor to actually great works, the production needs to say something.

As an academic curiosity Anyone Can Whistle was interesting. As a piece of theater, its point of view was unclear. Sperling indicated at the beginning of the show that this work is “more relevant than ever in these crazy times.” After last night’s performance, I would need considerably more convincing to agree.

Photos: Nina Westervelt

Comments