After the smashing success of Opening Night’s premiere of Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut up in my Bones, the Met swiftly returned to business as almost usual with a rejiggered revival of its 2010 production of Boris Godunov. The fundamental change involved the company choosing for the first time the composer’s original 1869 version, its 135 minutes performed without intermission. One had to wonder if the company’s recent long closure had influenced the decision to suddenly embrace Mussorgsky #1?

Throughout the pandemic other US companies sliced and diced familiar operas into one continuous act so that audiences wouldn’t need to mingle during intermissions. We therefore saw 90-minute versions of Tosca, Il Barbiere di Siviglia and Carmen, etc. By ditching the sprawling three-act Boris seen in 2010, the Met would not only substantially reduce the running time and eliminate intermissions, it would also discard a Marina or Rangoni as the so-called “Polish” act is omitted altogether.

I for one really look forward to that act, and it proved a particular highlight of the original production when it featured the thrilling trio of Ekaterina Semenchuk, pre-crash Aleksandrs Antonenko and Evgeny Nikitin. But the loss of their scheming and seducing was more than made up for by the propulsive concision of the seven-scene first version.

Experiencing it in the theater for the first time, I was most struck by how the opera felt less about the Russian people and more about its title character, particularly as it now concludes with the powerful death of Boris, rather than the scene in the Kromy Forest.

This shift in focus seemed appropriate as Pape was likely the revival’s raison d’être. Performing with the Met for the first time since the winter of 2018, the German bass returned in characteristically rich and refulgent voice. Though the very top is no longer as secure as it once was, it remains the striking and instantly recognizable instrument Met audiences have enjoyed now for over a quarter of a century.

I happened to hear Pape in his second performance with the company at Lincoln Center in 1995 during the season premiere of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Amid the sterling cast of Karita Mattila, Ben Heppner, Bernd Weikl and Hermann Prey, the Nightwatchman’s ravishing offstage lines stood out. At intermission I took note of the new bass’s name; he’d debuted as the Speaker in Die Zauberflöte just two days before!

While Pape’s justly celebrated vocal gifts were on splendid display Tuesday evening, his dramatic limitations suggested once again that the haunted Czar is not one of his best roles. A great, authoritative Boris should dominate his scenes, and, while Pape dutifully went through the motions, one felt no fear nor pity for his character. It didn’t help that Stephen Wadsworth’s production offered us from the beginning a quivering Boris On-the-Verge-of-a-Nervous-Breakdown. And then there was also all that distracting hair business!

With a blank protagonist, Boris can become a trial but some of Pape’s colleagues rose to the occasion occasionally stealing the show from him, particularly Ryan Speedo Green as an immensely entertaining Varlaam. His big, buzzy bass-baritone rang out superbly and his rascally interplay with Tichina Vaughn’s imperturbable Hostess gave a welcome jolt to the evening especially after the long, inert Pimen-Grigory scene. Might there be a Boris sometime in Speedo Green’s future?

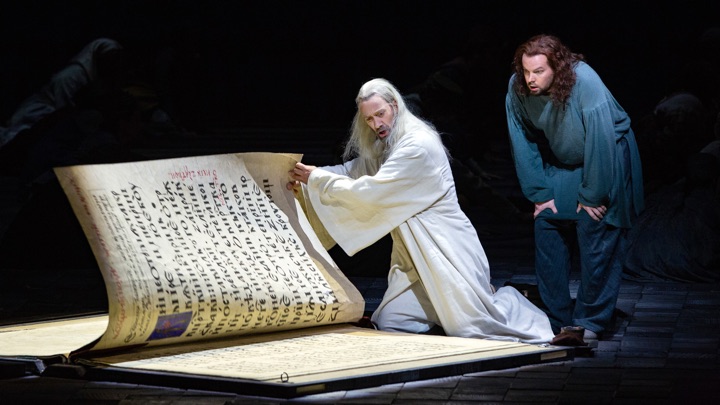

In his Met debut Estonian bass Ain Anger did his able best to animate Pimen’s long-winded story-telling, while fellow debutante David Butt Philip revealed a stirring sturdy tenor as Grigory but this version gives him relatively little to do. Another new artist the Met, Maxim Pastor failed to make much of an effect as the oily Shuisky.

While Aleksay Bogdanov, replacing the originally announced Alexey Markov, made his mark as Shchelkalov, I wondered if local favorite Richard Bernstein (a biting Nikitich) might not have been even more effective. Miles Mykkanen’s piercing, plangent tenor made much of the Fool’s lament, but his laughably frenetic gyrations and unnecessary prominence throughout was the jarring misstep of Wadsworth’s blandly efficient production.Amidst the flood of male voices, one was grateful for Erika Baikoff’s pleasant Xenia and Eve Gigliotti’s hearty Nurse. And as I’m allergic to boy sopranos (and countertenors) as Feodor, Megan Marino’s lush mezzo was a particular gift.

While one occasionally missed the colorful splendor of Rimsky’s reorchestrations, especially during the wan coronation scene, conductor Sebastian Weigle reveled in Mussorgsky’s harsh, unsparing writing and his orchestra played with fire and dedication. The chorus, which had sounded so splendid at the Verdi Requiem several weeks ago, began a bit off form but gradually warmed to its demanding tasks with the men on blazing form during the boyar council scene.

Commissioned by Peter Stein, the production’s original director, Ferdinand Wögerbauer’s dull, simple sets keep the action moving but add little atmosphere, though Moidele Bickel’s costumes do add some needed visual richness to the drama.

The season’s first HD transmission of this Boris Godunov is scheduled for a week from Saturday and may be most recommendable to those interested in experiencing Mussorgsky’s first thoughts. Perhaps by then someone will schedule a wig therapy session for the star.

Photo: Marty Sohl / Met Opera