This was an Occasion more than a musical event—I attended on Saturday—and the packed crowd (2500 people) in damned uncomfortable chairs in Damrosch Park beside the Met were clearly thrilled to be attending any such thing. Live music! People vocalizing, blowing, plucking, strumming, and the sounds coming out to our ears, not from screens. Masks, vaccination cards and i.d. were demanded of all comers.

This was a great and happy event, but it wasn’t so much a musical one. So much of the music was sacrificed to electronic amplification that one wonders if matters would not have been improved had the amplification been omitted entirely. True, the music had to fight off competition from helicopters overhead and sirens in the street (it was difficult to be sure which distant sounds were the offstage band Mahler calls for in his score, and which were traffic noises), but we might have gotten something more cohesive without microphones.

I’m sure the technical engineers are masters of their craft, but that craft isn’t one that melds well with the requirements of that virtuoso instrument, the 19-century orchestra, with its infinite array of colors, harmonies and individual timbres. Through microphones, the metallic could sound tinny, the drums and basses like rolling thunder, louder or softer than intended, the winds rich and keening but without the entwining support of strings.

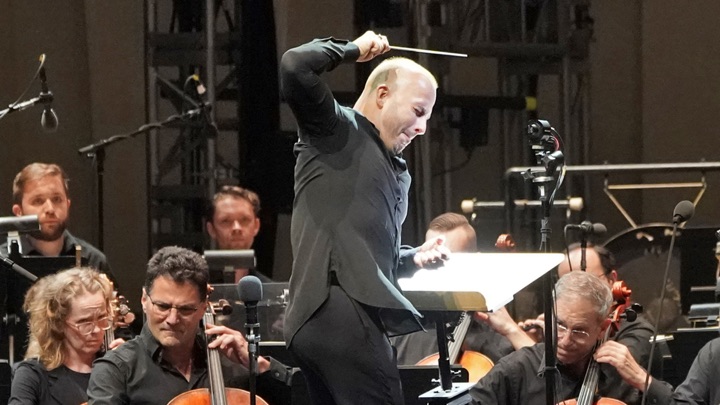

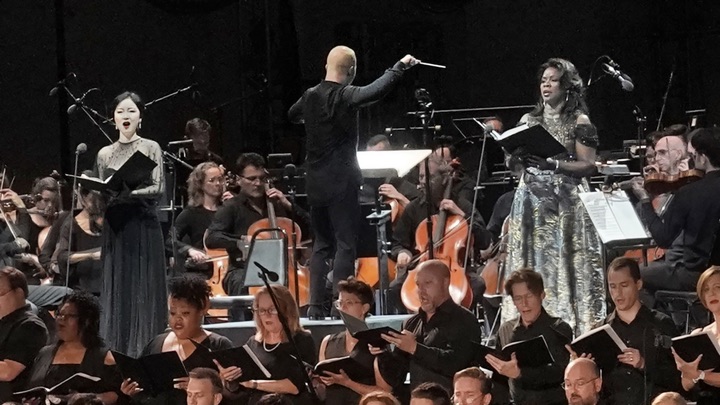

Met Music Director Yannick Nezet-Seguin, already a familiar and favorite figure on the city’s cultural landscape, leaped about energetically, directing instruments and holding the focus of the closed circuit cameras (so as to command the more distant sections following him on screen, not to mention the offstage band and the chorus), fluttering his fingers to express the proper dappled figures of harps or flutes. He directed a great deal of wonderful playing from individual sections of the orchestra, but there was insufficient blending.

The technical systems, it seemed to me, defeated coherence. Deep instruments were too deep, abyssal, and brassy calls came out of nowhere (an effect Mahler might have liked, actually). Delicate touches of harp or trumpet were loud as sirens in the night. The majesty of the conception was there, and the orchestral humor of Saint Anthony’s Sermon to the Fish (the third movement), and the holy hush of the choral epilogue. Somewhere in the bushes was a Mahler symphony, but the tigers and hyenas drowned it out. One would like to hear what Yannick does with this music—and these performers—indoors, in a proper acoustic.

httpvh://youtu.be/411gKEkIi58

The chorus sat in front of the audience, facing away from us so as not to breathe in our faces. Over other heads in the audience, we saw only the top row of heads. They turned to address us on cue, which was far less disturbing—it was rather thrilling—than a marching entrance would have been. In any case, had they been on bleachers behind the instruments, they would have lacked a sounding board behind them to push their music into the listeners.

Denyce Graves sang the “Urlicht” with a pronounced wobble and little fullness to her voice for this all-important sermon. Ying Fang, whose exquisite soprano usually fills the Met like a clear chime, made pretty sounds but was defeated by the microphones in the open air.

Splendid to hear music performed before our very ears after all this time, and by forces of such skill. But my joy was muted by the technological enhancement.

Photo: Ken Howard / Met Opera