Last fall, smack in the middle of the pandemic and against all odds – including one Hurricane Zeta – Atlanta Opera managed to successfully present Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci and Viktor Ullmann’s Der Kaiser von Atlantis outdoors in a circus tent with zero COVID transmission thanks to strict adherence to health and safety precautions among the audiences, artists and staff.

It’s not surprising to see that the experience and the indomitable resilience led them to grander scale stagings and more adventurous collaborations this time around. As reported briefly by my colleague Christopher Corwin in his Trove Thursday posting dedicated to Kurt Weill, Atlanta Opera is currently presenting a new version of his best-known work The Threepenny Opera (seen on Opening Night 4/24) alternating with another (shorter) adaptation of Georges Bizet’s immortal Carmen (promoted as The Threepenny Carmen); both billed as world premieres.

In the video below, Atlanta Opera’s General and Artistic Director Tomer Zvulun, who also served as the stage director for both shows, detailed the palpable excitement of going “back close to home” by performing in the Big Tent at Cobb Energy Center (the home for Atlanta Opera)’s parking lot.

In order to comply with the pandemic health and safety requirements and to limit exposure, the new version of The Threepenny Opera was confined into 90 minutes without intermission. Sanctioned, and even funded in part, by the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, it focused only on the seven lead characters, jettisoning much of Brecht’s dialogues and replacing them with a role of Narrator. The resulting work made it feel as if it were Weill’s opera with libretto by Brecht. Furthermore, Atlanta Opera revealed how it actually included all of Weill’s music in the video below!

The concise nature of the new version closely resembled to the score of Leonard Bernstein’s historic 1952 Brandeis University performance ) of Threepenny featuring Lotte Lenya, David Brooks and Jo Sullivan as part of the inaugural of its Festival of the Creative Arts. Adapted and translated by Marc Blitzstein (himself took the role of the Narrator), this eventually ended up as the version used in the wildly successful first Broadway revival in 1954.

Despite its popularity, in my honest opinion The Threepenny Opera is actually pretty hard to get right. As familiarity breeds contempt, everyone seems to have specific ideas of how the aesthetics should look like. This was reflected in most of the recent performance reviews; there were always complaints that either the performance wasn’t what Brecht had in mind (who actually knew that?), it wasn’t in the right language, or worse, it wasn’t sufficiently dark/disturbing/creepy!

At the center of this was the one aspect that made The Threepenny Opera so alluring – the vagueness or the lack of rigid structure around it, so much so that the musicologist Hans Keller called the piece “the weightiest possible lowbrow opera for highbrows and the most full-blooded highbrow musical for lowbrows”. As if that wasn’t enough, Brecht infused the lyrics with his critical point of view of capitalism, and by setting it among the lowlifes in Victorian England on the eve of Queen Victoria’s coronation, Brecht projected his own ideology on Weimar Republic into the piece.

Naturally, taste changes over time, and what was fresh and innovative before had significantly lost its shocking values these days. Furthermore, as written recently, the advent of social media accelerated the distribution of “toxic disinformation” and satire had been rendered “quaint and futile” in the process. The same thing happened with The Threepenny Opera, methinks. While Weill’s songs were evergreen, Brecht’s words could significantly lose their impact on the listeners, even though his message was still very much relevant to the world we live in. Therefore, it required extremely sensitive handling to be able to bring out an impactful Threepenny Opera to modern audience.

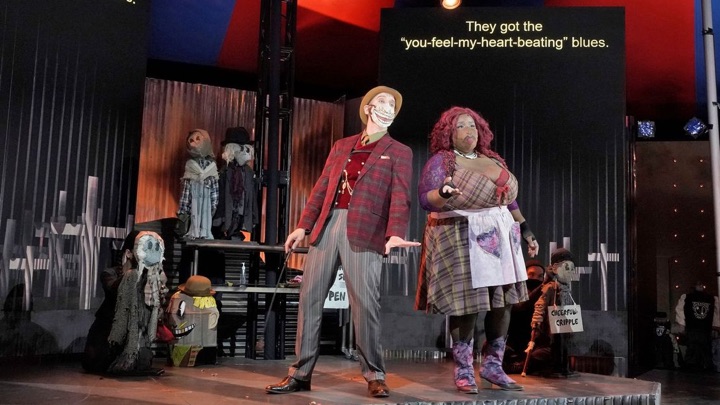

Zvulun solved the challenges of dealing with the pandemic constraints and the ultrasensitive tastes by presenting The Threepenny Opera in a world that was completely alien to mankind … inspired by graphic novels and filled by puppets as the prostitutes, beggars, gangsters, and constables! It was a stroke of genius, really – not only that the puppets replaced the large number of supernumeraries usually required to represent the British underworld, but they also were able to do things that would be objectionable to real-life humans!

Collaborating once again with Center for Puppetry Arts (the largest organization dedicated to the art form of puppetry in the US) but on a much grander scale than last year’s Pagliacci, the puppets – designed by Jason Hines – didn’t just merely function as props, they actively participated in the opera; they “sang”, danced, high-fived their human counterparts, even “commented” on the actions happening on stage. Jon Ludwig, Artistic Director of the Center for Puppetry Arts, served as puppet collaborator in this production, and he seamlessly interwoven the 20+ puppets into the story; there were times that I simply forgot I was watching puppets in action!

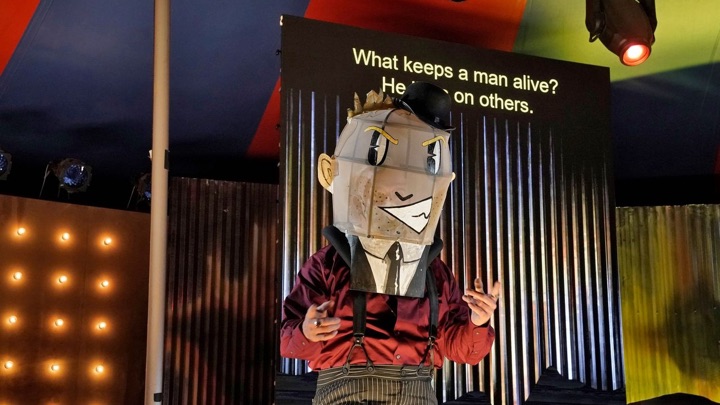

The puppet world also saturated that of the human singers. All of them were masked the whole time for this staging; each mask was decorated with specific expression that characterized the singers, drawn similarly with the expressions of the puppets. Even further, costume designer Erik Teague created giant heads (they looked like decorated space uit helmets) worn by the singers in certain particularly big scenes. Erin Teachman bright and engaging projections on two LED screens at the back of the stage completed the look and feel of the production, tying it all together into a unified front.

Speaking of Teague’s costumes, he shifted the era from Victorian closer to the times of Weill and Brecht’s lifetimes. Perusing a bold color palette dominated by black and red, there was no mistaken that these were dangerous creatures, ready to sacrifice everything and everyone for their own self-interest. Only Polly wore lighter colors in the beginning of the opera (perhaps to signify innocence), but soon she changed clothes and joined the gang.

Teague’s pièce de resistance manifested in his treatment for Brecht the Narrator. Teague’s sketch above definitely suggested a certain influential figure in TV; in fact, the opera began with Brecht changing jackets and shoes into the clothes in the sketch, reminiscent of the familiar opening of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood! It was a sheer brilliant move by whoever suggested the idea; the parallel of such an educational show with The Threepenny Opera should bring the audience into the proper mindset of interpreting and enjoying the opera (even if this was billed “Adults-Only”, unlike the TV show!)

The multiple ends of the stage proved to be useful for keeping considerable distance among the singers and the puppeteers, ensuring smooth transitions between scenes, and keeping the continuous flow of the performance. There was decidedly industrial look of the set pieces, appropriate for an “opera for beggars”, softened only by a shiny colorful disco ball lookalike that housed Marcella Barbeau’s lighting and reflected beautiful patterns on the roof of the Big Tent.

All these superlative elements supported Zvulun’s vision, which was decidedly traditional in interpretation and pretty straight-forward in direction. Nevertheless, he choreographed the movement extremely well, and the whole piece moved in a such a breathtaking pace from start to finish with so many complex details embedded into the show.

There were times that I wished I could see it again just to capture all the nuances and intricacies that were happening on stage. In addition, by placing the audience sitting on either side of the stage, and having the singers and puppets sang and moved around, Zvulun managed to create a sense of intimacy between the performers and audience (that was usually lost in the big opera houses), despite all the social distancing measures.

Speaking of social distancing, Atlanta Opera once again upheld gold standard in compliance with health and safety protocols, including paperless tickets and programs, health screening questionnaires, temperature checks and mandatory face covering throughout the show. Unlike the fall performances, this time the tickets were sold as “pods” of two people (the left side of the stage) and four people (the right). The distance between each pod had been shortened to 3 feet following the health guidance, yet all other safety precautions left intact.

Atlanta Opera assembled quite a first-rate cast for this presentation, and boy, did they deliver! Any productions of The Threepenny Opera would rely heavily on the central character Macheath (or Mack the Knife), as he would have to charm his way to the audience that they would root for him no matter how evil he actually was. In this regard, Jay Hunter Morris was certainly up to the challenge. His Macheath was simultaneously sly and slick, dangerous and charming at the same time.

Interestingly, his Macheath brought to my mind the one role that made him famous, Richard Wagner’s Siegfried, being an impetuous (anti)hero that had no care for the world (much to Weill’s chagrin, I assume!) Morris’ voice sounded round and full, and I was pretty taken aback at how well he enunciated the words, even while being masked! His take on the famous “The Ballad of Mack the Knife” (yes, that famous song was assigned to Macheath in this production) could be heard on the trailer below. Watch how the way he swung his blade as if he was a descendant of Sweeney Todd!

On the other hand, Gina Perregrino employed her dark mezzo voice to portray an ice-queen Jenny despite her red-hot ensemble, as if her Jenny was still bitter from the last Macheath’s encounter! Her duet with Macheath on “Pimp’s Ballad” was like the textbook case of what not to do with your ex… my only quibble was that I wanted more tango on that number!

As the King and Queen of the beggars, Kevin Burdette and Ronita Miller made a sinister, scheming, larger than life couple. Burdette’s sinewy baritone and Miller’s sonorous mezzo voices complemented and contrasted each other; their constant bickering, aided by the puppets, lightened the mood and was definitely one of the highlights.

Polly is always the sole role that undergoes the most transformation in The Threepenny Opera, and Kelly Kaduce – no stranger to the role since she performed it at Boston Lyric Opera three years ago – brought in sensitive reading to both sides of Polly throughout the night. Her “Pirate Jenny” in particular, imbued with so much hopefulness that her rendition was decidedly different from the famous Lotte Lenya version.

Baritone Joshua Conyers, one of Atlanta Opera’s current Glynn Studio Players, sang his Tiger Brown role authoritatively and earnestly, you almost couldn’t believe that he would betray his friend Macheath (but just like the real world, it did happen!) His duet with Macheath “Cannon Song”, complete with a short synchronized dancing with his constable puppets, was a sight to behold. Unfortunately, his fellow Studio Players Susanne Burgess, who played his daughter Lucy, suffered the most from the pandemic constraints, as her high-flying coloratura sounded extremely muddled behind the mask. Nevertheless, her catfight duet with Kaduce “Jealousy Duet” brought down the house and was truly a highlight!

Atlanta Opera brought in veteran actor Tom Key to represent Brecht/Mister Rogers the Narrator part, and his wide-eyed excitement was essential to move the story along and demarcate the sections of The Threepenny Opera (it has three acts, after all!) A day after the Opening Night Morris released an essay about how Key inspired him to pursue onstage career some 40 years prior, and after reading that article, you couldn’t help to have teary eyes remembering the end of the show, where both Morris and Key sang the reprise of “The Ballad of Mack the Knife”. I couldn’t imagine how it felt to be sharing the stage with your childhood hero!

Conductor Francesco Milioto, who made Atlanta Opera debut with this performance, led the orchestra aplomb in a reading that was full of vigor and vitality. It almost felt like a miracle how the orchestra, who like last fall, performed from a different tent, synched beautifully with the singers for the most part; their sound transferred to the Big Tent via speakers. Even on the Opening Night, everything was running so smoothly like a well-oiled machine!

Going back to the Dalai Lama quote above, Atlanta Opera clearly demonstrated how to transform challenges into opportunities with these performances, and the efforts were certainly reasons to be celebrated, not only for Atlanta, but for the US opera landscape in general. Here’s hoping that Atlanta Opera would continue their innovative endeavors, even after they are able to come back inside to Cobb Energy Center home. Personally, I would be very sad if they never returned to the Big Tent again, for I enjoyed these performances immensely, pandemic or not!

Production photos by Atlanta Opera; seating photo by Michael Anthonio

Comments