CAMERON KELSALL: It certainly gets my vote. One thing that struck me during this rewatch was that even though I know the plot inside and out, I still found myself hanging off the edge of the couch, waiting for every twist and turn. It’s so engrossing—and I don’t just mean Chandler and Wilder’s intricately woven script, although it’s a marvel of genre-movie writing. The entire world Wilder, his cast and artistic team create sucks the viewer in…when Fred MacMurray talks about being able to smell the honeysuckle in the Los Feliz hills above Glendale, you’ll swear you can smell them too.

DF: As a native Los Angelino—and lover of its history—I was continually thrilled to see the city and environs used so evocatively. Two examples that I think are pitch-perfect: the house that the Dietrichsons (renamed from the novel’s Nirdlingers) live in, which as you say, is above Glendale, is exactly the right spot for their imagined upward mobility; and the scenic setting of an intimate conversation in the hills above the Hollywood Bowl will take your breath away.

CK: Los Angeles in the ‘30s and ‘40s was Ground Zero for noir, and it makes perfect sense—the city looks so shiny and sterile in the daytime, but as dusk settles in, it takes on a completely sinister character. Wilder and cinematographer John Seitz capture this perfectly, as even interior shots have a chiaroscuro effect that makes every conversation and tryst seem even more diabolical than it actually is.

DF: It’s simply breathtaking to see some of these compositional moments. MacMurray showing up in his last meeting with Stanwyck is like a densely saturated painting. And in terms of dark tone, it’s every bit as compelling. The first ten minutes of this movie—beginning with a wild ride through a foggy pre-dawn L. A., through Stanwyck’s stunning entrance—provide as good a definition of “film noir” as anyone could come up with.

CK: I’ve always believed that genre films like noirs and Westerns live and die on casting, and you really can’t beat MacMurray, Stanwyck and Edward G. Robinson in a role that should have won him an Oscar. (He wasn’t even nominated!) I’m sure we’ll have plenty to say about Stanwyck, the ultimate forties femme fatale, but I want to begin with the men. I don’t think the movie would work so well without a stolid, squared-jawed leading man type like MacMurray in the lead. He’s no one’s idea of a great actor, but he has the unteachable ability to make any piece of dialogue, no matter how hard boiled, sound entirely natural, like he just thought it up in the moment. And he strikes the right balance of good guy and unscrupulous menace that he makes the character’s journey believable—he’s an earnest factotum who, in the hands of the wrong woman, doesn’t think twice about throwing his life away from the promise of a cheap thrill.

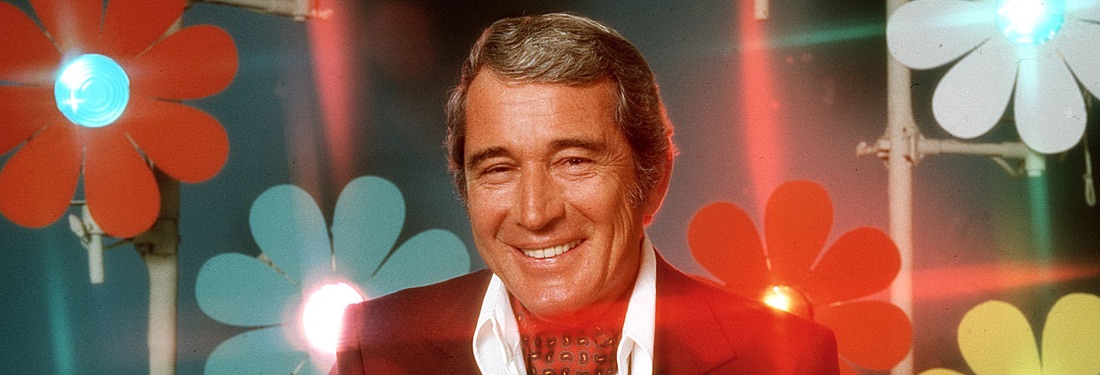

DF: Your mention of “the wrong woman” makes me think we should probably acknowledge that this movie, like most films noirs (oh, hell—like nearly all movies of the era) needs us to adjust to its time. But before leaving behind Fred MacMurray, may I just say: hot cha cha! I grew up watching him as the dithery, essentially neutered father on My Three Sons, and I guess that imprinted on me early; though I had my share of gay prepubescent TV dad crushes (Mark Miller in Please Don’t Eat the Daisies springs to mind), it never occurred to me to think of MacMurray as sexual. But here, he positively smolders! There’s a famous trope in Double Indemnity that has him lighting matches with a flick of his fingernails. Yet I kept wondering why he bothered; surely just one look from him and they’d spontaneously ignite.

CK: The supporting cast is strong across the board too, with lots of flashy small parts. Robinson, of course, steals scenes left and right as the pugnacious insurance claims investigator who cracks MacMurray and Stanwyck’s plan wide open. But it’s worth mentioning Tom Powers as the unfortunate husband who gets bumped off, Jean Heather as Lola, Stanwyck’s pouty stepdaughter, and Byron Barr as her wrong-side-of-the-tracks boyfriend. Recognizable character actress Betty Farrington is also a hoot as the Dietrichsons’ world-weary maid.

DF: Agreed on all counts. (And Farrington gets the film’s best line: glaring at MacMurray, who has come to make a sales call, she ushers him into the living room with, “They keep the liquor locked up.”) I don’t think there’s a better example of Robinson on film than this, which is really saying something. My memory of the novel is that the character of Lola is a real piece of work—she’s softened here, as are several other elements, but Heather gives her some flash. What became of her? And also of Barr, who is as good or better than most of the “troubled young leading men” actors who worked this genre. Well, Cameron—are we ready for the main event? (Or at least, the element that brought us to Double Indemnity.)

CK: Indeed. Stanwyck certainly excelled in a variety of genres, but noirs like Double Indemnity really capture what made her such a memorable actress. Her performances are layered without seeming overly fussy—she can come across as manipulative and sincere at the same moment. That quality really comes in handy here. Throughout the film, we’re never fully sure whether anything Phyllis Dietrichson says is true, and Stanwyck has the audience in the palm of her hand, controlling us not unlike she controls MacMurray’s Walter Neff. The aforementioned final scene is, to reluctantly use a word I abhor, a revelation.

DF: I sometimes think that Stanwyck—one of my great favorites—is the unlikeliest female movie star of this era. She’s striking, but not traditionally attractive; she’s not soft and pretty, but she also doesn’t have the great bone structure of Davis or Hepburn. Her voice is nasal and has a hint of Brooklyn twang that she never lost. All of that is evident here from the beginning, and I also can’t imagine any other leading lady who would have put up with that god-awful wig. Yet all of it comes together here in a way that’s exactly right, and electrifying. As you say Cameron, like many of the greatest screen actors, she sometimes seems to be doing very little. But watch her gazing dreamily off-screen, her mouth set into something between a half-smile and a sneer, and your blood will run cold.

CK: Stanwyck, of course, had a somewhat rough-and-tumble background, and she never entirely lost that coarseness even though she undoubtedly ascended to the upper echelons of Golden Age stardom. It’s a quality that suits this style of film very well, and I hope we can explore it even more in movies like Sorry, Wrong Number and The Strange Loves of Martha Ivers in weeks to come—not to mention classics like Stella Dallas and Golden Boy.

DF: Oh, go ahead—twist my arm. I’m up for more Stanwyck anytime, and as we have teased out, we’re also going to look at another of my favorites, Susan Hayward. Before we go, I’d just like to say one more thing about Double Indemnity. It too has some considerable changes from the novel, which were necessitated by censorship rules of the time. That makes it all the more amazing that the movie is so strong, but I’d also recommend reading Cain’s short, jaw-dropping novella. It’s not your normal Thanksgiving fare, but I promise you’ll be grateful that you did.

Comments