CAMERON KELSALL: I last watched this version just a few months ago, after reading a biography of Kim Stanley (seen here, in her final acting role ever, as Big Mama), and came away with much the same conclusion. To me, it’s indicative of a frustrating problem that cuts across many Williams adaptations—a surfeit of strong individual elements, but little sense that the piece hangs together as a unified whole. Though, I will say, this Cat seems more together than most. Unlike many of the teleplays we’ve considered so far, this one is actually directed by a Tony-winning theater director, and I’d venture that accounts for its relative success.

DF: Your first point—the difficulty of finding a coherent wholeness in Williams—seems to me very similar to a problem that’s often commented on about Anton Chekhov’s plays. And indeed, to me Williams, especially here in Cat, hits Chekhovian themes of family and frustration. Honestly, I think Cat is immensely difficult to bring off—so many moving parts! In this production, Lange’s performance is itself a study in pluses and minuses. I admire the go-big-or-go-home nerve that sets it in motion, and there’s obvious intelligence behind every moment. But she pushes the beginning almost into camp, frantically clawing the air and using the broadest Southern accent imaginable. (I transcribed this: “Ma luuuuuuhhhhvly layce drayyyusss.”) Later, she lightens up, and some of the quieter moments are marvelous, but the damage has been done.

CK: Some of Lange’s choices can come across as overwrought, although I would attribute at least a percentage of that to the rudimentary filmmaking on display. (This adaptation was a co-production of Showtime, then in its infancy, and KCET, the Los Angeles affiliate of PBS.) During Maggie’s Act I monologue/aria, the camera often captures her in tight one-shots, expanding and distorting every movement to almost cartoonish levels. The physicality of her approach might read with more subtlety had there been a greater sense of back-and-forth in the cinematography. Her accent is a little overstated, though perhaps that was inevitable, playing against two Texans: Tommy Lee Jones (Brick) and Rip Torn (Big Daddy).

DF: Jones was the big positive surprise for me here. I had remembered him as oddly cast, and it’s probably fair to say that David Dukes (who plays Gooper here) is more traditionally handsome and suave—conventional casting would likely reverse them here. But I think this is far more interesting. I love Dukes’ drily bitter take on Gooper, and Jones seems to me a revelation. His dark, hooded eyes always suggest something going on under the surface, and he plays the long arc of Brick’s gradual unraveling with tremendous precision. He and Dukes both use understatement to great effect.

CK: Jones himself was a notable college football star; he speaks with authority when he describes the highs and lows of life between the goal posts. I agree that it’s a surprisingly vital take—more than other Bricks I’ve seen, he suggests the character’s brokenness and dissatisfaction with the direction of his life, an ability to recognize what’s going wrong but not to change it. He and Torn also generate an appropriate sense of tension in their long scene together—perhaps fueled, if Stanley’s biography is to be believed, by personal animosity. Whatever the source, it’s thrilling to watch a Big Daddy and Brick who are actually drawn to and repelled by each other.

DF: Torn to me should be nearly ideal—including that there’s often a streak of genuine rage and meanness underneath the surface, which can benefit Big Daddy. But as I find often with him, the performance is inconsistent, veering wildly from moments of absolute commitment, to something resembling clownish self-parody. I think of Torn as a walking demonstration of great talent unfettered by self-discipline.

CK: For an actor as ebullient as Torn, I found him most affecting in his quietest moments—I was particularly struck when, at his most unguarded, Big Daddy confesses that the drive to amass wealth is a shallow means of keeping death at bay. There is also something poignant in Torn’s youthful appearance: Although the play takes place on the eve of Big Daddy’s sixty-fifth birthday, Torn here is only fifty-three, and his person is trim. The character’s certain demise reads differently when he’s presented as still believably vital.

DF: Agreed—and also, the fact that Torn is still quite handsome underscores the striking backstory of the plantation’s original owners—two gay men who were clearly attracted to the then-young Harvey Pollitt. As I said earlier, happily that point is not softened here, as it is so often.

CK: Torn does have a tendency to showboat, though, and that’s when the performance approaches parody. If Olivier at his worst was playing Col. Sanders, Torn at his worst is playing Foghorn Leghorn.

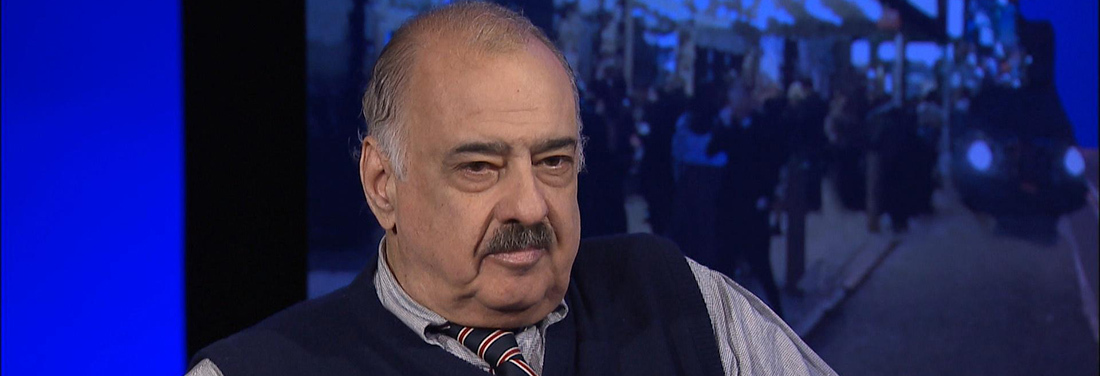

DF: Speaking of actors who might be called “unpredictable,” we have Kim Stanley here as Big Mama, which I can imagine involved some risk, given her… well, shall we say, personal unpredictability? But what she delivers is absolutely sensational. She has pretty much everything the role needs—she’s big-hearted, sloppy, embarrassing, vulgar, delightful, and mercilessly, penetratingly insightful. And she’s also funny as hell—I laughed out loud at her telephone conversation with Miss Sally in the Gayoso Hotel, a scene that could serve as a textbook acting lesson.

CK: Stanley’s life and career are mired in tragedy—one of which, I would say, is the relative scarcity of filmed performances she left behind. Among other things, she proves absolutely comfortable and natural on camera, something that’s never guaranteed from stage actors. I don’t think I’ve ever seen as compelling a breakdown as she displays here in Act III, where she loses her composure without sacrificing her dignity. Intelligence, indeed. Stanley won the Emmy for her work here; also nominated in the same category was Penny Fuller, sharp-tongued as “Sister Woman” Mae.

DF: Stanley is so virtuosic here that it was probably inevitable she’d take the prize, but Fuller is really her equal—the rare Mae who finds the waspish humor but also seems like an actual person.

CK: As a pair, Fuller and Dukes are superb too. They really suggest Mae and Gooper’s manipulative nature, with crocodile tears barely concealing their desire to take over those 28,000 acres. Brick and Maggie may have their issues, but it makes sense that Big Daddy would recognize them as his kind of people—they’re many things, but they’re not phony.

DF: In that final scene, the trio of actresses here—Lange, Stanley, and Fuller—really makes us feel the power shifting from the male characters to the female ones; it’s something I think Cat really needs, but rarely achieves. Well Cameron, I’m sure we could both go on… but shall we save some of that for our next Cat reports? I’ll just say in closing that I strongly recommend watching this version as a benchmark for what the play is all about.

CK: Warts and all, this adaptation captures the play as Tennessee Williams intended it. It’s a must for casual admirers and hardcore fans alike.

Comments