“Having just the vision’s no solution.”

Though a number like “I’m Still Here” might fall into the trap of camp performance, a deeper look at the structure of the song says a good deal about Sondheim’s postmodern tendencies. In a way, Carlotta is just another example of a Sondheim character whose narrative is presented that of failure in life.

However, to focus on a linear narrative about life that ends in failure calls into question the viability of the narrative form itself. This gives leeway for experimentation and innovation with structure, which Sondheim achieves with this number, telling a linear life story with a questionably optimistic ending in a nonlinear way as narrated through events in pop culture.

Its gradual, nonlinear coalescence is a metaphor for the character and a small-scale model for the show as a whole. It’s at junctures like these that Camp Sondheim mingles with Postmodern Sondheim in structure and message.

“The postmodern looks for breaks, for events rather than new worlds, for the telltale instant after which it is no longer the same,” says scholar Frederic Jameson in Postmodernism, Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. “The ‘When-it-all-changed;’ as Gibson puts it, or, better still, for shifts and irrevocable changes in the representation of things and of the way they change.”

In crafting his musicals, Sondheim’s focus, regardless of genre, tends towards the processive. In fact, many of the songs in Sondheim’s musicals are commentary on the action on behalf of the characters – for the songs to advance the plot would be a betrayal of traditional modes of human communication. Instead, they’re more about synthesizing feelings or emotions.

As previously stated, Sondheim reflects postmodernism and the postmodernist reorganizational tendencies in his various genre experiments and pushing the boundaries of temporality within his own musicals. The mixing of the past and present through the “young” versions of the principal four characters is an example of this.

Additionally, similarly to the way “I’m Still Here” is framed within the context of a non-linear non-narrative, Sondheim tends to favor themes in his musicals that emphasize and set up for fragmentation. Themes like marital strife, miscommunication, and reclamation or redemption of villains are all fair game with Sondheim.

In capitalizing on these themes of failure, it opens Sondheim up to explore narrative structures which form the basis of some of these genre experiments.

However, the other half of Sondheim’s postmodernism comes on demonstrating the processive, visibly constructional elements of his songs that climax in a “when it all changed” moment. An example of this is “Sunday” from Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George, a musical that can be seen in many ways as Sondheim’s postmodernist manifesto.

“Order. Design. Tension. Balance. Harmony.”

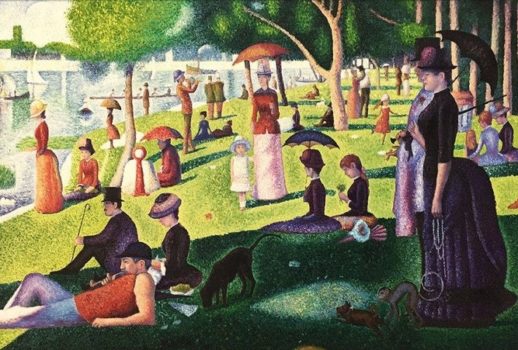

Inspired by Georges Seurat’s painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, this show depicts a fictionalized version of Seurat’s quest to finish his most famous painting and reconcile his art with the world around him. In the second act, the action is advanced forward from the 1890’s to the 1980’s where Seurat’s grandson, George, is also struggling to make an impact with his own art.

Though its temporal setting would seem camp prone (Paris in the 1890’s and Chicago in the 1980’s), Sunday is a sincere and affectionate look at an artist’s relationship with his society and his subjects. That relationship, it turns out, is one of organization. The creation of the painting is the pivotal moment of the musical and the finale of the first act.

As Act I nears its conclusion, the squabbling secondary characters fight their way towards the center of the stage. George, at this point recently deserted by his frustrated mistress, Dot, watches the squabble and as the cacophony builds, the effect is overwhelming. But once urged by his mother, George takes control of the tableau and the final number begins. He dictates, “Order. Design. Tension. Balance. Harmony.”

As the song progresses, both its structure and the accompanying narrative action are processive on the part of the artist. Structurally, the song is only a single sentence the characters sing as they shift into place:

The observed objects, grass, trees, water, are all described in terms of their composite colors, blue, purple, yellow, red, just like the composition of Seurat’s pointillist paintings. The sentence builds upon itself to gradually create a visual description of the painting in a structured, sequential manner to create a whole product both verbally and visually onstage by the end. Indeed, bit by bit, the painting comes together through words.

In the libretto, George is “moving about, setting trees, cut-outs and figures – making a perfect picture.” As he literally moves and arranges the frozen characters, Sondheim reveals the artist as an organizer of society’s moments. As Seurat makes order out of chaos, so, too, does Sondheim until the picture is finished on the climactic final chord.

However, as the final chord is sustained by the chorus, the orchestra plays a dissonant distortion of the arpeggiated chord that recurs throughout the musical – though the characters are fixed in place in this photo, the issue of artistic vision and endurance will endure (and actually open the second act). Though this picture reflects a moment frozen in time, the nature of art is something much larger and more drawn out.

Sunday is one of Sondheim’s most emblematic works because it’s his most persuasive piece on behalf of the artist. However, something like Follies is equally significant in articulating the Sondheim sensibility which is primarily postmodernism with elements of camp grafted in through calculated structure and, to a certain degree, individual interpretation of the artist.

Alexis Smith, camp casting but not a camp performance.

Ignoring camp entirely would have made the creation of Follies as we know it impossible, but to interpret it as exclusively camp is to lose significantly on its value and ignore its radical, non-linear organizational elements that make it both cinematic and a moody, early concept musical.

This could be why Follies was not a critical success at its premiere and provides insight into the review by Walter Kerr that praises the work of the individual actresses but criticizes the structure.

Ethel Shutta, Mary McCarty, and Yvonne De Carlo come off best, Miss Shutta jabbing a rhythmic finger at us as she thrusts one foot forward and teaches us what it is to place a song, Miss McCarty seeming to shoulder the sky aside as she shouts, “Who’s That Woman?”, Miss De Carlo smokily insisting, “I’m Still Here” (“When you’ve been through Herbert and J. Edgar Hoover/Anything else is a laugh”), though she doesn’t—in all truth—look as though she’d been anywhere. . . .

Unfortunately, the liveliness here is all left-field, and the legitimacy in the love stories that ought to give the evening its solid foothold is skimpy and sadly routine.

Through examining Sondheim as approaching camp versus viewing Sondheim as a staunch postmodernist, we realize that even on a structural level, Sondheim attempts to create a manifold and varied depiction of the modern era through a sampling of various aesthetic modes.

Often using and reinventing the postmodernist modes of conceptualizing the world, Sondheim as a camp figure is nonetheless (and potentially despite it all) a part of the Sondheim mythos. Looking at Sondheim also gives insight into the inherent similarities of the camper and the postmodernist and how each one goes about crafting their view of the world, the camper as a viewer and the postmodernist as an acting agent.

At the end of the day, Sondheim’s ability to manifest as both in so many performance traditions makes his genre experiments a genre unto themselves, one right with camp, postmodernism, and further insights about human nature. As long as one approaches that genre with an open mind, the versatility of Sondheim’s work ensures that one won’t walk away empty-handed.

Photos: Martha Swope (Smith); Matthew Murphy (Gyllenhaal).

Comments