This was not a performance as gimmick. Whether it was the playfulness of “Tom, Tom, the piper’s son!” or the haunting “Malo, Malo” refrain, Hewitt was able to vocally and dramatically mine the character’s innocence and the deceptive ambiguities lying beneath the surface.

Nearly matching her was soprano Joan Hofmeyr as Flora. She too was able to temper her maturity of voice and convince as the younger sibling. If on occasion—during Flora’s more dramatic moments—indications of her “real” voice did emerge, it did little to break the spell.

However, in the pivotal part of the Governess, Annaliese Klenetsky did not have a success. The role should dominate the opera, but the soprano often failed to make much vocal impact. Klenetsky’s singing came off as small, tentative and pinched, particularly in the first act. Perhaps it was opening night nerves, or perhaps the role is simply too big for her voice at this point in her career.

That is not to say that there weren’t moments of merit. When not pressed, as in the bedroom scene with Miles in Act Two, the voice is quite winsome and appealing—if decidedly soft-grained. The character’s more dramatic moments, such as her “Who is it, who? Who can it be?” in the opera’s fourth scene, call for a rhythmic clarity and power that was not there.

The voice is more responsive to quiet allure than declamation, and one wished for forceful precision rather than neatly produced tone.

Yet despite any vocal shortcomings, Klenetsky did create a credible dramatic character. One rarely encounters a singer so close in age to the 20-year-old Governess, and there was much to be gained by this.

In large part due to Klenetsky and the director’s conception of the role, the inclusion by Britten and librettist Myfanwy Piper of Yeats’s “The Ceremony of Innocence is Drowned” finally made sense to me. Is it not to the Governess, rather than the children, that this resonates more?

Katerina Burton’s lovely, clear, and unusually youthful Mrs. Grose proved an asset in all of her scenes. Chance Jonas-O’Toole as the Prologue seemed somewhat vocally underpowered and hesitant, but dramatically he emerged as an almost ever-present silent witness in this production.

It was the performances of Charles Sy as Peter Quint and Rebecca Pedersen as Miss Jessel that totally dominated the opera. Each ghostly appearance galvanized the proceedings. Both voices distinct and individual in character. Both singers conquering the vocal demands of their roles.

Sy’s melismatic call to Miles sent a jolt of electricity through the house. Britten’s writing here is mysterious and sensuous (Have 16th notes ever felt so erotically charged?), and the tenor took full advantage of the opportunity. His voice has the hallmarks of the role’s originator Peter Pears, but whereas Pears’s voice could take on a flute-like quality, Sy’s baritonal underpinnings create a more viral virile impression.

Dramatically he presented an ominous yet seductive presence and was the perfect counterpart to Pedersen’s tortured Miss Jessel. Britten does not provide Miss Jessel with music of a complimentarily sensual nature. Whereas Quint’s music is perfumed and accompanied by a celeste, Jessel’s is sinister and haunted – her appearances heralded by a gong.

Yet despite these musical limitations, Pedersen’s performance was in many ways as alluring as that of Sy’s. Her singing was rich and full-bodied: evenly and impressively produced on both extremes of the soprano’s range. In a role that is often undercast, Pedersen overwhelmed.

Britten’s chamber opera (which considering its complexity was written astonishingly in just four months) is a fascinating score. Its architectural tonal world is relentlessly in flux. Anticipated resolutions rarely occur. The listener is deliberately kept off-balance and in a constant state of unease. The mortar that Britten uses to bind it together are the 15 interludes between each of the opera’s scenes.

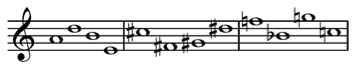

Each interlude is a variation of the twelve-tone “Screw” motif introduced during the opera’s prologue. They are in many ways the heart of the opera. Conductor Steven Osgood and the 13 members that comprised the orchestra did a masterful job of conjuring the interludes’ contrasting moods and locations.

The twelve-tone “Screw” theme.

Elsewhere there were a few times, particularly in the “On the paths, in the woods, on the banks, by the walls” section in the First Act’s final scene where the tempi seemed plodding rather than lithe, but that is a minor quibble.

Director John Giampietro and scenic designer Alexis Distler have set the action at Bly in a single windowless decaying manor room. The room’s peeling walls—with hidden and trap doors—support what is left of a collapsed ceiling. The oculus created by the collapse adds a sense of impending dread but also relieves a sense of claustrophobia.

Kate Ashton’s especially evocative lighting design and handsome costumes by Audrey Nauman complete the schema.

Just as Britten uses the interludes as a connective tissue, so too does Giampietro use them for similar effect. There is a fluidity to his staging. The dramaturgy is always thoughtful, and he does not shy away from underscoring the story’s many ambiguities while creating a few of his own. Yet any variations from the actual stage directions stemmed from a reasoned conceptual conceit.

Perhaps the director’s biggest and most successful digression was in the staging of the opera’s final scene. The score clearly indicates that Quint should be heard from off-stage. In Giampietro’s staging Quint looms largely in the room. He is resolutely at the Governess’s side.

As the Governess presses Miles for the name of “who do you wait for, watch for? Who? Who? Only say the name and he will go forever” and he finally shouts, “Peter Quint, you devil,” the director has Miles run toward the Governess and Quint, but who is it he is really running to? Before Miles can reach Quint, the Governess grabs the boy into her arms.

Miles does not immediately die. He and Quint mirror each other with outstretched arms and remain thus all through the Governess’s “Malo” lament. It is only in the final measures of the opera that Miles expires at last with Quint’s arms still reaching for the boy. “What have we done between us?” Indeed!

I fear that Britten’s last chamber opera will never become a staple of the repertoire. Its appearances are few and far between. For me, this score feels like it will never reveal all of the mysteries so masterfully embedded in its pages by the composer.

Any opportunity to see The Turn of the Screw is an opportunity to unlock more of those mysteries, and I am especially grateful when the opportunity is a production as thoughtful as the one presented by Julliard and its creative forces.

Photos: Rosalie O’Connor

Comments