The only impressions I remember are the astonishing beauty of the voice of Benita Valente as Ilia and the furious histrionics of Hildegard Behrens in Elettra’s third act aria. But I have a distinct memory of the handsome and stately production of Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, featuring a giant head of the god Neptune with its gaping maw serving as entrance and exit at key moments.

So when the curtain went up on Sunday afternoon’s Lyric Opera of Chicago revival, I was surprised and delighted to find it was the same Ponnelle production borrowed from the Met, looking spiffy and beautiful and unchanged since 1983! David Kneuss has directed the revival with great warmth and skill, and Lyric’s musical forces provided an afternoon of superb, if lengthy music making that served Mozart’s 1781 opera magnificently.

Those readers who know my musical tastes will not be shocked to find that I have a somewhat conflicted view of Mozart’s operatic works. I adore the sublime melodies, the generosity of spirit, the long lyric lines, and the delicacy of emotion expressed in these works.

But at the same time, I find the endless repetitions tedious and deplore the somewhat cutesy playfulness of operas like Cosi fan Tutte and The Magic Flute. Happily, Idomeneo is firmly rooted in the opera seria tradition, and, while there are plenty of repetitions in its lush score, the opera features deep explorations of the themes of love winning over hatred and the victory of unity and mercy over revenge.

The plot centers around King Idomeneo of Crete, shipwrecked and near drowning, making a bargain with the god Neptune that if he is saved from death, he will sacrifice the first person he sees. This turns out to be his son Idamante, though all the years of the Trojan War have passed so that they don’t immediately recognize each other.

Idomeneo’s torment about how he can appease the god without killing his son forms the heart of the opera, along with Idamante’s growing passion for Ilia, the captive daughter of King Priam of Troy, causing severe angst for his paramour Princess Elettra of Argos. There are moving arias reflecting the themes of love vs. duty, family vs. national honor, familial love vs. vows to the gods.

And in the final act, Neptune unleashes a monster to attack the Cretans, but the god finally relents as he sees the triumph of Ilia and Idamante’s love, and all (except the bitter Elettra) are reconciled.

Lyric’s handsome production is elegant, stately, and traditional in the best sense. And its cast of splendid singing actors is uniformly elegant.

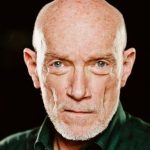

Tenor Matthew Polenzani plays the troubled Idomeneo as a dark, conflicted monarch with delicate emotion and tender vulnerability. His singing is meltingly beautiful throughout, tinged with many colors—his second act “Fuor del mar” was a master class in Mozart style and musical grace and garnered the afternoon’s largest ovation.

Equally impressive is Lyric debutante Angela Brower in the “pants role” of Idamante, her bright timbre and physical dexterity illuminating the role, and she has excellent chemistry with the Ilia of Janai Brugger. Ms. Brugger sang with liquid and limpid beauty and a real grace of bearing that made her loving scenes with Idamante utterly believable. Her opening aria “Padre, germani, addio”, where she laments the loss of her family in Troy, was sung with sensitivity, delicacy, and moving emotion.

As the scorned Elettra, soprano Erin Wall almost steals her scenes with her furious arias in Act One and Act Three where she calls down the Furies to exact revenge—no fury like a woman scorned indeed. But I thought Ms. Wall’s formidable soprano seemed a bit squeezed and she seemed to be internalizing her anger instead of letting it burst forth. The voice never seemed to bloom, but the character was played vividly and frantically.

There is able support from David Portillo as a flexible-voiced, honey-toned Arbace; Whitney Morrison and Kayleigh Decker as the women of Crete; Josh Lovell and Alan Higgs as the Trojan men; Noah Baetge as the High Priest of Neptune; and David Weigel as the Voice of Neptune.

The chorus in Idomeneo, representing the people of Crete and the freed Trojan captives, is yet another vital character in the opera. The Lyric Opera Chorus under Michael Black responds to the challenge magnificently, providing a stunning wall of sound sung with precise diction and dexterity.

The chorus is here required to use unison stylized gestures in response to the events of the opera, and they effectively move as one and reflect the emotion of each moment beautifully. Likewise the Lyric Opera Orchestra, playing with delicacy under the sensitive but authoritative baton of Sir Andrew Davis, garnering many “bravis” at the start of each act from an audience obviously sympathetic with their recent strike.

At its best, Mozart’s music is haunting and even healing, especially here when expressing the quiet joys of reconciliation at the opera’s end. While I thought the afternoon could have used some gentle cuts to the many repetitions at the end of arias (when the supertitle screen goes blank, you know they’re merely repeating the previous text), it was an afternoon of profound beauty.

Photo: Kyle Flubacker