My own reaction to the HD broadcast–surely a different experience, for better or worse, than the one Lincoln Center patrons had–was equivocal. I enjoyed looking at the work of Kentridge and his design team, while feeling that other productions had made more of this opera’s horror, tragedy and black comedy. I made an effort to put that evaluation out of mind and consider Kentridge’s production anew for the living-room take, but at the end of three hours, I found I had arrived at the same place.

To begin, a quote: “We have a culture in which people applaud scenery when the curtain goes up. At the Met, this is an instantaneous isn’t-it-pretty reaction, and most people never go beyond that–to them, the scenery and costumes are the production. I regret this. Obviously, to you and, God knows, to me, the full measure of a production is drawn from the experience you receive from the singing and the acting within this setting and how all that relates to your expectations and knowledge of the piece.”

The man who said that, in a 1987 New York profile, was the originally scheduled conductor of the Kentridge Lulu, James Levine. He was responding to a critic/interviewer’s challenge regarding the bland pictorial productions that were his theater’s norm in that era.

There is an argument to be made that an important theater should lead its audience rather than knuckle under and spoon-feed it what it expects, but there is something to Levine’s observation. Engage long-time Metgoers on productions, and you often find that they most remember what a production looked like. This one was beautiful; that one was ugly. This one had bright colors; that one was all gray. This one was lavish; that one looked cheap. An inquiry about the actual direction that (one hopes) accompanied the designs may not yield much.

Many of the productions in the Met’s repertory in 1987 have been replaced, but what I sometimes refer to as the “all perimeter, no center” approach is still very much with us. The planks and projections of Robert Lepage‘s Ring, and the sea of lights in his L’amour de loin, have more in common with the later, completely decorative work of Franco Zeffirelli than may initially seem apparent. These are productions that fill the eye and do not dig very deeply. They display rather than dramatize the operas.

Kentridge’s Lulu is a somewhat better example of the “framing” approach. Maybe the approach was an understandable one in box-office terms. Kentridge had made a hot ticket of Shostakovich’s satirical The Nose–a stronger production than Kentridge’s Met followup, in my opinion. Lulu, like The Nose, is a hard-sell opera. Although it is older than almost anyone who would be in a theater to see it in 2015, it still is widely perceived as forbidding “new” music.

But a viewer familiar with Lulu, someone who has seen what can be achieved with it in the theater, may feel that questions it poses were not answered here, nor really considered. Such a viewer may also feel that the singing actors were left to their own devices, to varying effect, rather than molded into a true dramatic ensemble. In an interview among the disc’s bonus features, the leading lady comments, lightly and without malice, that Kentridge is “not a regisseur.” One sees what she means.

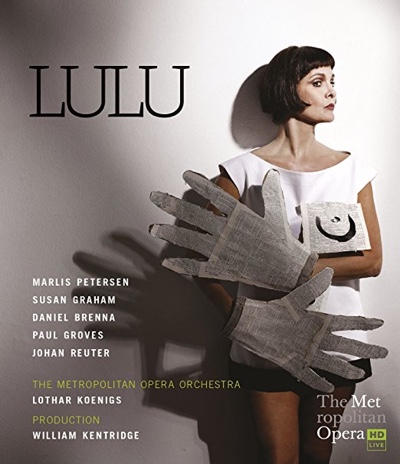

What Kentridge is, rather than a director, is an acclaimed visual artist. His Lulu is striking in design, from the continuous, elaborate overlay of animated projections (combining Kentridge’s ink drawings with film footage and text) to Sabine Theunissen‘s Art Deco sets to Greta Goiris‘s stylish costumes. Two silent, stony-faced performers, a hunchbacked servant in tuxedo (Andrea Fabi) and a pianist/Lulu double (Joanna Dudley, very graceful), hover onstage throughout like Expressionist phantoms, delivering props and effecting scene changes, or physically responding to the music.

The projections, designed by Catherine Meyburgh, evoke the pursuits of Lulu‘s characters: art (The Painter), music (Alwa) and especially print journalism (Doctor Schön). Sometimes a line from the libretto is quoted in the projections either before or after we hear it sung (e.g., “I used to dream at night of the man made for me”). The words jump out at us like a tabloid headline or a sensational pull quote.

The happenings of the libretto are faithfully if plainly, sometimes awkwardly, enacted. The job is done with some concern for fidelity–entrances are appropriately timed, and no character who is not “supposed to be” on stage ever is, setting aside the two mimes–but the libretto is driving the direction more than the music is.

All of Lulu‘s characters present a director and cast with an array of options, but only a few big choices are made, such as Countess Geschwitz very openly flirting with Lulu in the presence of Schön. I would have no idea, if this were my first Lulu, why Schön’s last words before expiring are “The devil!” Nothing in the blocking makes it clear. A more experienced operatic stage director, working with his premiere cast, probably would not have Alwa staring out at the audience while demanding a kiss from Lulu.

By 2015, Levine, whose health struggles have been well chronicled, was not up to conducting this long-time specialty, a work he had introduced to the Met in 1977. The theater was fortunate to secure an experienced Berg conductor, Aachen-born Lothar Koenigs, then 50 years old. The qualities of clarity and precision in Koenigs’s conducting are more in evidence on the Blu-ray release than they were in the Met HD cinema showing, which had the typical soupy, voices-forward mix.

It would be fair to call Koenigs’s a “cool” Lulu–he is not trying to bring Berg’s score to the decadent expressive boil others have pursued–but the orchestra’s work is up to its highest recent standards. There is a nice spring to the scherzo-like movements of Lulu’s quarrels with Schön, and every motif is clearly voiced. The conductor’s work is elucidating in effect.

Marlis Petersen, an experienced Lulu, had announced her plans to relinquish the role when the Kentridge show closed. Vocally, she was going out in good though not peak form. The middle register can sound underpowered and colorless (mostly in the early scenes); highs are accurate and piercing but effortful. Petersen is in terrific physical shape and throws a lot of energy into her work. It is the sort of performance we see when a singer knows a role well and has to fill in some blanks herself. When a dramatic situation presents a clear, obvious option, the soprano pursues it powerfully. Elsewhere, her intentions are harder to read.

Susan Graham, by contrast, was new to Countess Geschwitz. She comments in her interview on the disc that Geschwitz’s music was unlike anything she had sung, and that she struggled to memorize and master it. Her first-class musicianship and mature artistry conceal that struggle. She brings interesting and sometimes touching ideas to the role, seemingly pursuing a Geschwitz in thrall to Lulu, as all of Lulu’s doomed suitors are, but with traces of self-possession that make her more than a pathetic creature. The argument with Lulu in the Jungfrau Railway scene has high voltage, staying just this side of a catfight, and Geschwitch’s spotlight opportunities in the final scene are as poignant as they should be.

The principal men fare less well, seeming adrift. Johan Reuter has a promising voice for Doctor Schön/Jack the Ripper, and sings the role with fresh and beautiful tone, but Schön seems less important than he should. There is something of an artistic stature gap with Petersen’s hard-bitten, forceful Lulu, and I missed any sense from the production that this man, loathsome though he is, is Lulu’s fated one, her equal. Franz Grundheber, the Schigolch, gives the impression of having a good time and being happy to be back after an 11-year absence from the Met. This esteemed Wozzeck of many productions, 78 and vocally craggy, inhabits Berg’s world with casual ease. The direction does not ask much of him, and he sails through, unperturbed.

Daniel Brenna, a baritonal tenor who had sung Tannhäuser and Siegfried by 2015, does not find much of the lyricism in Alwa’s music, nor does he give the character much of a face or point of view. He makes heavy weather of his contribution to the final scene’s ensemble, in which several characters who have pursued Lulu to their ruin react to her portrait. Another tenor, Paul Groves, mostly shows preoccupation with maintaining vocal altitude. The Painter’s anguished wish to exchange places with Goll’s dead body goes for little (one should not think it would be an even swap). Groves is more effective in his return as Lulu’s second customer, the African Prince.

There are compensations in briefer roles, when singers can saddle up on a single attitude and ride it for a whole scene. Martin Winkler gets things off to a strong start with a commanding Animal Trainer (behind a 1930s microphone), and he has fun spitting and mincing through the longer role of the odious Acrobat. Elizabeth DeShong‘s Wardrobe Mistress, Schoolboy, and Page are big-house vocal luxury, and bass Julian Close‘s Theater Manager/Banker is an encouraging Met debut.

Just as it is difficult to get them to turn out for Lulu at the Met, it is difficult to get them to stay once they have done so. An overhead view during final ovations shows more empty seats than we usually see in Saturday HD broadcasts. I suspect more of those seats had been occupied at the start of the afternoon. Nevertheless, Kentridge’s Lulu has been recorded as one of the theater’s successes of this decade. If its visual ingenuity and flair made it easier for some members of the audience to spend time with Berg’s intricate and, I believe, quite beautiful music, and ultimately to warm to it, I am grateful for this. Anyone who enjoyed the production in 2015 can buy with confidence; the broadcast looks and sounds very good on the Blu-ray release.

However, when I think back on the great productions of Lulu I have seen, several of which were filmed, I always remember some telling bit of business, something the people on stage did. Who could forget Jack the Ripper slowly ascending those steps and vanishing into the moonlit night (Patrice Chéreau); Lulu watching the ballerina’s Black Swan with admiration and envy and perhaps self-hatred (Krzysztof Warlikowski); Lulu erotically licking the Painter’s blood from Schön’s fingers, as Schön’s face registers revulsion, horror, need (Christof Loy, my favorite of the easily available DVDs)?

I have seen Kentridge’s production twice, the second time a day ago, and I find it difficult to call to mind any particular stage picture from it. Most of what stays in my mind is a jumbled impression of ink collages and the legs of Marlis Petersen. The collages are often stunning, the legs even more so, but there is more in Lulu than that.

Comments