Anna Moffo made some of the most entrancing records ever. Their appeal is to “voice fanciers.” (I understand. We’re a despised group.) But Moffo’s best work renders us helpless.

Luckily, after a few years with EMI Moffo was signed by RCA Victor and the great producer, Richard Mohr, with his ace engineer Lewis Layton, in what was the golden age of stereo recording. They had cut their eye teeth on Toscanini, befriended Fritz Reiner and Charles Munch and with the Chicago and Boston symphonies come up with the “Living stereo” records starting in the mid-fifties—still some of the best captures of symphony orchestra sound in history.

Mohr, a “closeted” voice fancier, invented a way to record singing that was clear and clean, yet totally honest. Moffo and her various orchestras are placed in a recognizable space, she is “above” and slightly “behind” the orchestra, so the balance always seems realistic. There is no effort to exaggerate the size of her voice, nor is she given a “pop singer” presence. Mohr and Layton set two microphones to the best of their ability and let the conductor do the rest. Balances within the orchestras represent the maestro’s ear, his blends and contrasts are immaculately captured and the interplay of Moffo’s timbre with the sonorities achieved is simply magic.

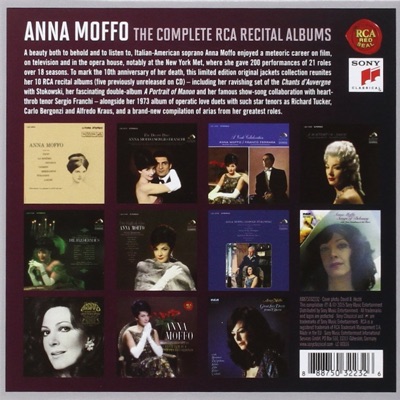

In Sony’s new collection of all her RCA recitals, 12 CDs offered at an astoundingly low price, the sound has been polished by a discreet remastering. The result is a three-dimensional clarity without any loss of naturalness. One can “hear” the space in which she and her orchestras are working, her sound shimmers over instruments that are completely natural sounding and the results are mesmerizing. Mohr had trained a group of associates who trade off these various records with similar results.

Anyone is going to test this remastering by listening to one of the great vocal long-playing records ever made: the Rachmaninoff “Vocalise,” Villa-Lobos’ “Bachianas brasilieiras No. 5” and a selection from Canteloube’s “Songs of the Auvergne,” conducted by Leopold Stokowski no less with “The American Symphony Orchestra” from 1964.

Stokowski summons gorgeous playing from the orchestra, lush but detailed and never overdone; his ability to keep the Rachmaninoff alive despite the slow tempo is as amazing as his witty rhythms in the Canteloube. Moffo’s sound, shadowed sweetness, sits within this framework. She has a caressing nostalgic allure in the Canteloube, an exotic sexual promise in the Villas Lobos and spins an otherworldly hypnotic spell in the Rachmaninoff. It’s all been recorded countless times but no one ever has done any of it like this. Given additional presence and detail as “cleaned up” here one would wear out even a CD if that were possible.

Another incredible recording is the Verdi arias accompanied by the wonderfully astute Franco Ferrara. Every aria is given an impeccable framework which Moffo fills with improbable beauty. She wouldn’t have sung most of these roles, yet her feeling for the style, the easy spin of her singing in difficult music, the float, the beautifully formed words are wonderful (and rare). She has an effortless virtuosity in the “Bolero” from Vespri and “Ernani involami,” which has a delectable lilt and stunning precision in rhythm, an incredible trill as well as astounding high notes.

She is a heartbreaking Desdemona. Even lacking an Emilia she creates an atmosphere of increasing dread, of girlish dreaming which quickly turns into terror. She spins out the refrain, “Cantiamo, cantiamo… salce…” with devastating sweetness. The complete honesty of the recording allows the orchestra to well up as it does from time to time, emphasizing the character’s fragility and youth. The way her timbre contrasts with the winds is utterly magical. It’s not the only great account of the scene but it is unforgettable and very moving.

Sony offers the original record jackets and notes (but one needs a magnifying glass to read them) and a booklet with thorough production details and a bromide-filled but harmless note by Jürgen Kesting.

All the recital LPs are here, from her first for RCA The debut recital in 1960 conducted by Tullio Serafin to her last for them, Heroines from Great French Operas. With Serafin, she does astounding things, incredible trills, astounding ascents in alt, phenomenal agility… but then there is her heart. One hears it instantly in Liu’s arias which are improbably gorgeous. Anyone who saw her in the insanely competitive Met revival of 1961 knows how devastatingly moving she could be.

There are two additional CD length collections of selections from her complete operas for RCA, including two little arias from her delectable La Serva Padrona (this is short enough to have been included complete).

Four recitals have never been released on CD before. Of greatest interest are two devoted to The Portrait of Manon album from 1963, the first, highlights from Massenet, the second, from Puccini, with two selections from Massenet’s morceau Le Portrait de Manon. These are conducted by the great serialist (!) René Leibowitz. Manon features Giuseppe di Stefano, of all people, as des Grieux and Manon Lescaut offers the wonderful, pocket-sized and shamefully underrecorded Flaviano Labò in the equivalent role. Good supporting people were engaged including everybody’s favorite Anna di Stasio.

Massenet’s opera was a disappointment for Moffo at the Met. She was given a new production which she did 10 times in 1963-64. The garish, clumsy production was hated and she was judged a disappointment. (In the house, she and Gedda sounded small and looked undirected. When the Met brought this to Philadelphia they were both much better. Her soft- focused sound didn’t blaze through some of the bravura, although it was well delivered, but her honeyed tone floated effortlessly around the smaller house and she was quite touching.)

On the CD, she sings alluringly throughout but without a lot of personality. Surprisingly in the generously represented first two acts, it is Di Stefano who is unforgettable. Singing as lightly as possible and crooning a lot he manages a role he obviously understood totally with enormous charm and far more sweetness than on any of his other stereo records. Yes, he makes a meal of Le rêve, but it is abundant and delicious.

In act three he has some rough spots but remains in surprisingly good voice for this period, his French is excellent and he even suggests endless vulnerability. Moffo only trumps him with “Nest-ce plus ma main.” truly X-rated singing. In the final scene, he is more heartbreaking than she.

This all changes in the Puccini. She is so spectacular one can only regret Victor failed to record her complete, although the role would have been a big sing for her live in the huge Met. She has total command of the style, abundant imagination and depth of feeling and she sounds ravishing.

It is not a “big mama” Manon. Instead, this is a sentimental girl with a big heart and impulse problems. She gets the complete scene with Lescaut (a fine-sounding Robert Kerns) that frames “In quelle trine morbide,” so she offers pouting then longing and an endless legato line with breathtaking pianissimi. In the big duet with des Grieux (Labò sounds wonderful!), she has total immediacy. Her expression of fear that she has lost him, “Son forse della Manon d’un giorno, meno piacente e bella” is as heartbreaking as I’ve ever heard it. Her soaring upwards at the end of the duet is thrilling,

Luckily, she gets the scene with that perv, old Geronte, where she mocks his looks and age. She sounds like a little girl making a teasing joke rather than a roaring bitch, it’s a wonderful effect. She sings over the chorus in act three, her voice has substance and she moves higher and higher effortlessly. Labò is thrilling in “Guardate, pazzo son.”

“Sola, perduta, abbandonta” sung like a child who is suffering terribly but doesn’t understand why is very moving and they are both wonderful in the final moments of the opera.

Leibowitz who was French-born really goes to town with Puccini, he’s even a little over the top with rubato and wild emphases. He sounds bored with his countryman, Massenet.

“Trippy” might have been the word members of a certain generation would have used to describe Moffo’s 1965 collaboration with Sergio Franchi, called The Dream Duet. Franchi was one of that legion of pop tenors described as “operatic”, although compared to say, Andrea Bocelli, he sounds like Lauritz Melchior. He was a huge name in a vanished era where the music of the people could actually be sung by a voice like his. He appeared on broadway, became a superstar in Vegas, sang for Presidents (reportedly startling John F. Kennedy with his volume in the national anthem) and was a regular on the many variety shows on TV. And of course, his records were best sellers.

He had a fine natural voice, poor pitch sense and didn’t know how to use the head voice for getting into the top (he was no crooner). He is a butch, frequently flat partner for Moffo. The arrangements made (one might guess on ‘shrooms) are by Henri René. From the left come barrages of string tone, from the right horripilating eruptions of brass, from the middle shrieks from the winds and then—by beatific miracle—a celesta sounds, tinkling over the noise. This is the only “multi-mike” record made by Moffo in this series. It doesn’t sound as though she and Franchi were in the same space, not only because each has a separate acoustic (as do all the instrumental groups) but because one suspects a lot of time was spent getting him to sing somewhat close to the pitches. It’s a big hoot, but be warned!

Moffo had a great feel for the kind of popular music known as “legit.” Her record with Skitch Henderson, a wonderful conductor, called One Night of Love is so treasurable one wants to offer it for canonization. The songs, from Broadway and operetta, are perfectly chosen and the lush but inventive arrangements show off Moffo’s remarkable range from that sexy bottom to the soaring top but never in ways that seem wrong or “operatic”. Her spontaneity and sense of fun and her gift for nostalgic melancholy are on display as are stunning high C’s, beautifully inflected words and tons of charm.

In her time Moffo was compared (less than favorably) to Maria Callas and Victoria de los Angeles, and she offered her first Met Lucia the week after the elemental Joan Sutherland stopped American presses with her Met debut in the same role. But none of those great ladies could possibly have made a record like One Night of Love.

The Great Moments of Fledermaus, made in Vienna, conducted by Oscar Danon, is nothing special, although Rise Stevens barks through Orlovsky’s aria, Franchi struggles with pitch as Alfred (poor Richard Lewis gets to throw in some of Eisenstein) and George London sings Br?derlein with much feeling but rough tone. Moffo is fine but not quite memorable. The “old-fashioned” translation (as Sony describes it) is passable but not always clear.

The sad finale of this collection is Moffo’s last RCA recital, made in 1974, two years before she stopped singing opera (she never really “retired”). Called Heroines from the Great French Operas, it documents her vocal crisis. Not every aria is badly done, although all have an aura of caution, but some are unwisely chosen, such as Juliette’s Waltz Song or “D’amour l’ardente flamme,” which exposes the most worn part of her voice and which she can’t sustain.

Moffo was called a lot of names before she died, including “has been” and “failure.” One of the virtues of this Sony release is that it is in effect a (very affordable) votive candle to human possibility. Where did the miracle come from that allowed this poor girl to achieve so much beginning with so little? The miracle came from her for on these records burns the magic of a great human spirit, something Anna Moffo proved can shine in the midst of all the puzzlements and miseries of life on this planet. Grazie, Sony—and brava, Anna!

Comments