In fact, what appears as an unlikely motto is an exchange of lines from Waiting for Godot:

ESTRAGON: We always find something, eh Didi, to give us the impression we exist?

VLADIMIR: Yes yes, we’re magicians.

And at least the beginning scenes of the opera have a strong Beckettian tang. The curtain rises to reveal an ambiguous interior space suggesting a public area of a theater. A low ceiling is pierced by skylights (or perhaps circular lighting fixtures) and a series of shallow risers extend upstage into semidarkness where the foot of a broad staircase can be glimpsed. Curiously, the floors are covered with threadbare Persian rugs.

One of the carpets unrolls itself, revealing a middle-aged man in tatty, worn evening clothes: this is Moses. Bass-baritone Robert Hayward (surely at Kosky’s behest) takes very literally the line “Meine Zunge is ungelenk,” not so much stuttering as having a sort of momentary episode of panic every time he tries to utter one of the adjectives describing God. The Voice of the Burning Bush is heard—from singers distributed around the circumference of the auditorium, so the sound seems to come from everywhere and nowhere—commanding Moses to remove his shoes, which he sets aside only an instant before they burst into flame and—apparently under their own power—stroll offstage.

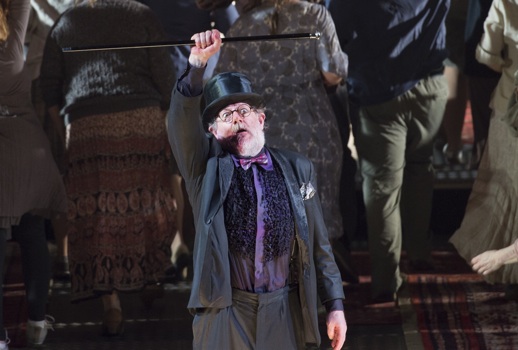

From nowhere a walking cane appears in Moses’ hand, then vanishes again, then reappears. It obviously a prop, not genuinely magical at all, and Moses seems to be performing these tricks involuntarily, accidentally. When Aron (tenor John Daszak) arrives, he’s sporting a crisp white dinner jacket and electric-blue slacks, like a cruise ship compère. His handling of the magical illusions is a lot more expert than his brother’s, and we realize that, at least from Aron’s point of view, he’s the star of this downmarket vaudeville act, with Moses as a stooge or fall guy.

So Aron’s slick words of exegesis are in this context mere razzle-dazzle: something to catch the attention of an audience not really capable of understanding Moses’ (by definition) ungraspable idea of God. He does a whole routine with a “floating” cane, and either by accident or design, the thread is visible.

The working of the various miracles (or, in this context, “miracles”) falls to the expert Aron: he produces brightly-colored silks, directs Moses in “healing” his leprous hand (obviously a glove, but when exactly did he take it off ?), and then produces a glass of water which Moses drinks and then immediately vomits back up as blood.

There is no intermission, just the lowering of the front curtain leaving only Moses visible. In silence, he does an oddly disturbing little magic act, producing a scarf adorned with the Star of David, vanishing the scarf, and then producing it again, but this time as plain white silk. Back and forth he goes: Jew, not a Jew, Jew, not a Jew. The implication, I think, is that this uncertainty about his identity is what has kept Moses on Mount Sinai for those long 40 days and nights.

The earlier energy of the crowd is greatly surpassed in the “Wo ist Moses” chorus; I really thought those singers were going to hurt themselves with all that jumping and flailing, but in fact they not only survived but sang the overlapping lines with pinpoint precision. Aron turns blasphemous really quickly, summoning the Elders to prostrate themselves at his feet. The crowd strip off their watches and jewelry, piling it all into an old woman’s hat, and she dutifully shuffles offstage with the trinkets as the Calf of Gold rises on a stage elevator.

The Calf, though, is not a statue but rather a dancer dressed as a showgirl, in a plumed headdress, a stylized belly dancing costume and gold body paint. As she begins to gyrate, Aron turns the crank on an old-fashioned movie camera which projects a flickering strobe light onto the dancer. Somehow the light seems to bleach the hue from the dancer and everything around, creating a sepia image recalling silent film.

The various soloists such as the Naked Youth peer out from around their dummies to sing their lines: there is no suggestion of realism at this point. However, the elderly woman who earlier collected the gold returns in a bedraggled version of the showgirl headdress, topless and smeared with gold paint. She freezes downstage just off center in a silent scream.

Now the action shifts from tame to utterly disturbing: the crowd begin to pummel and tear apart the dummies, flinging them in a vast heap until most of the stage seems to be covered with disfigured bodies. The allusion to the Holocaust is both explicit and grimly powerful. When there is nothing left onstage but a pile of corpses, we hear from a distance the scream, “Moses steigt vom Berg herab!” But the mountain the prophet descends from is a mountain of dead Jews; he can hardly keep his balance as he clambers over the tangle of limbs.

And Moses is not carrying tablets; rather, the Commandments have been inscribed into his very flesh, great bleeding gashes across his chest and back. Hayward is now naked but for boxer shorts, and Moses seems to be in a state of shock. The smashing of the tablets takes the form of a clumsily bungled suicide attempt. There are no people left alive to follow the pillar of fire except for Aron, who leaves Moses alone. “O Wort, du Wort, das mir fehlt!” sobs the maimed old man, who then wraps himself in a carpet and lies still. The curtain falls very slowly indeed, and even after the theater was completely dark, it took a minute before the applause tentatively began.

Moses und Aron is always a rather grim work, but this production dared to be more pessimistic than most. The reference to Godot seems to amplify the sense of futility in the piece, suggesting that Moses’ notion of God as incomprehensible, inexplicable idea was from the outset doomed to failure, and, by extension, that perhaps any kind of religion is by its very nature absurd and unworkable. What is left is a struggle with the concept of Jewish identity: for instance, was Arnold Schoenberg a Jew at birth? Was he still a Jew when he converted to Protestantism at age 24, or did he “return” to being a Jew in 1933?

Dramatically this was superbly disturbing, and honestly I have been turning this production over in my head almost since last Sunday night. Musically it was on if anything an even higher level, absolutely magnificent conducting by Vladimir Jurowski. His take on the work paradoxically combined transparent detail and shattering force; it seemed to hover right on the cusp between music and noise without ever crossing over. Nothing felt formal, but everything was perfectly, immaculately in place.

What’s more, the whole score had a sweetness and clarity, an almost Schubert-like feeling, but again without blurring or softening the harmonies or orchestral colors. This had the boldness only a star performance can offer: utterly personal and yet utterly convincing. (The only other real star performance I saw during my week in Germany was Valer Sabadus as Xerxes, though that was a different sort of case because the whole concept of that production was that the performer was a star. So I can’t swear that Sabadus would always deliver a star performance, but Jurowski I think we can count on to dazzle on every occasion.)

Hayward had the advantage in playing Moses of actually having a strong voice that he kept in check instead of what often happens in this opera, casting a singer who no longer can sing. The bigness of his Sprechstimme, louder most of the time than anyone else’s singing, conveyed a sense of majesty despite the down-at-heel persona he was assigned in this production. I personally prefer a more glamorous tone for Aron than Daszak summoned, but his insouciant ease in this terrifying music was just right. (He also has a great look for Aron, one of those open “actor” faces that seem, deceivingly, so sincere.)

The casting of the smaller roles is a testament to the Komische Oper’s repertory system: the Naked Youth, Michael Pflumm, is also the second cast Tony in West Side Story, and the Young Maiden, Julia Giebel, had sung Celia in Lucio Silla the night before!

As with the Herheim productions earlier in the Regietournee, I really do long to see this Moses at least once more, not only to catch more detail but simply because it was an experience so sublime as to bear repetition. Or, to put it another way, before I saw this production, I respected Moses und Aron; now I’m fascinated by it.

Photos: Monika Rittershaus

Reach your audience through parterre box!

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

-

Topics: barrie kosky, cher pubic, komische oper, regie, waiting for godot

Latest on Parterre

Merry Widow | Finger Lakes, NY | July 25-28

Geneva Light Opera’s production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow will feature prize-winning baritone Bryan Murray and soprano Alexis Olinyk in the superb acoustics of in the landmark Smith Opera House in Geneva, New York on July 25, 27, and 28. A small city on the north end of the largest of NY’s Finger Lakes, Geneva…

Geneva Light Opera’s production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow will feature prize-winning baritone Bryan Murray and soprano Alexis Olinyk in the superb acoustics of in the landmark Smith Opera House in Geneva, New York on July 25, 27, and 28. A small city on the north end of the largest of NY’s Finger Lakes, Geneva…

parterre in your box?

Get our free weekly newsletter delivered to your email.

Comments