Certain operas are better in theory than practice. Boito’s Mefistofele has some undoubtedly fine tunes, and is perhaps neck-and-neck with Boris Godunov as a top bass star vehicle. But as an opera, it only works in fits and starts. For one, the fidelity to Goethe’s Faust gives the libretto a rather episodic, detached feel.

Gounod’s Faust might be a lot cheesier but it’s also more tightly focused and thus better theater. Boito’s opera has some some stunning choral work in the Prologue and Epilogue, a famous tune in Margherita’s lament “La altra notte” and an extremely enjoyable “Walpurgis Nacht” act but also a lot of filler. It’s not a long opera but it feels endless.

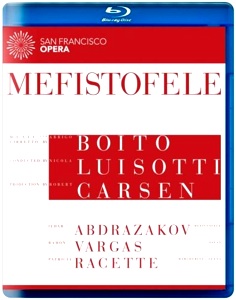

San Francisco Opera’s 2013 revival of Robert Carsen’s by now classic production is also one that looks better on paper than in actual execution. The production is as fine as ever—a very effective, timeless production that has enough doses of camp and visual splendor to maintain interest. Carsen goes farther with the by-now overdone “show within a show” trope than most directors—there are nods to commedia dell’arte, baroque opera, and French grand opera traditions as Faust and Mefistofele make their journey to hell and back. Costumes and sets seem to have been refurbished and look bright, colorful, and vibrant. No complaints about this production.

The musical values however leave something to be desired. When this production opened it was a star vehicle for Samuel Ramey. In his prime he was a genuine bass with charisma to burn. Ildar Abdrazakov seems to be under the mistaken impression that he’s more than a pleasant lightweight bass-baritone. He’s cute, and looks fairly good shirtless but the voice lacks the weight and gravitas that this part needs. He also lacks the kind of joyful malignity that I imagine famous scene-stealer Fedor Chaliapin brought to the part. Although a review in the invaluable Met archives seems to indicate that even Chaliapin couldn’t stave off the boredom of Boito’s opera:

A pity that the great Russian basso should have come forward in a work so tiring to the average listener, though full of interest to the student of operatic history. True, the character of Boito’s spirit of evil, a big, heavy brutish creature, forceful and mighty, but without the subtleties we are wont to associate with Mephisto, gave to Chaliapin an excellent opportunity for displaying his gigantic frame, his magnetic temperament, his dramatic power in big effects and his remarkably robust voice. But the ordeal of taking into the bargain so many dreary wastes, where music fair to make up for dramatic deficiencies, proved too much for a large portion of the audience, and before the close of the presentation rows upon rows of chairs in the parquet gaped empty.

Abdrazakov is just working with his voice’s built-in limitations. Ramón Vargas (Faust) and Patricia Racette (Margherita/Elena) are two fine artists whose voices are in precipitous decline. Vargas has recently cancelled a slew of engagements, and one can hear the troubles in this video: a strained, whitish top, a wobble, and (most dismaying) even his middle now lacks the sweet, ingratiating timbre that used to be his trademark. Vargas was never much dramatically and his Faust is a total cipher. I hope this treasurable tenor can recover some of his vocal goods.

Racette is even more problematic. I know she’s a San Francisco Opera institution, beloved not just for her devotion to the company but for her championing of new works and steadfast professionalism. That being said, she’s pretty much unlistenable at this point. The always smallish, vinegary lyric soprano now sounds unbearably shrill and curdled and any sustained tones bring out a Callas-like wobble. “L’altra notte” sounded like my cat when she whines for some tuna. And even her dramatic instincts fail her—she overplays both the girlishness of Marguerite and the glamour of Elena without being convincing as either.Conductor Nicola Liusotti and chorus master Ian Robertson are the stars of the evening—the chorus and orchestra sounded amazing. In fact, they overpowered the small-scale singers in almost every scene. Which was a mixed bag—all it did was serve as a reminder that this opera calls for grander soloists than the ones cast. The splendor of Carsen’s production is another double-edged sword. This Mefistofele was all dressed up with nowhere to go.