The key to enjoying Bellini’s I Capuleti e Montechi is to do a hard factory reset and reformat your brain to forget all other works based on Romeo and Juliet. Forget Tchaikovsky’s fantasy overture. Forget Prokofiev’s ballet score. Most importantly, forget Shakespeare’s play. If you can do all those things, you can enjoy Bellini’s opera for what it is—a primo ottocento relic with some very beautiful music.

Romani’s libretto makes the “star-crossed” lovers story less a tale of missed chances and senseless violence than a very conventional love triangle. There’s Romeo who is in love with Giulietta, daughter of Capellio. Giulietta is of course bethrothed to another (Tebaldo). And Romeo and his Montechi family are responsible for killing Capellio’s son. Much singing and sadness results. Romeo does indeed die of poison in the tomb but Giulietta expires from the same Unexplained Operatic Death that afflicts her Wagnerian sisters Elisabeth, Elsa, and Isolde. As I said, forget the Bard and it will all make sense.

Felice Romani’s libretto was not even commissioned by Vincenzo Bellini himself. The libretto had been used by a composer named Nicola Vaccai. That opera had premiered five years earlier and the part of Romeo was considered a choice part for the leading ladies of the day. Two famous Romeos, Giuditta Pasta and Maria Malibran, decided to incorporate Vaccai’s tomb scene into Bellini’s opera for their own Special Diva Edition. Not that Bellini could claim much originality for his own opera—many of the arias self-borrowed from the earlier opera Zaira.

The Bellini melodic magic is present in spades despite the patchy history of the work’s composition. Giulietta’s opening cavatina “Oh! Quante volte” is loveliness itself, as is Romeo’s opening aria (“Se Romeo t’ussice un figlio”). And the duets between Romeo and Giulietta are justly famous, especially the extended tomb scene. What the work doesn’t have despite all its tuneful prettiness is much dramatic voltage. Deadly feuds and violent thoughts are dispatched with melodies that sound generically romantic.

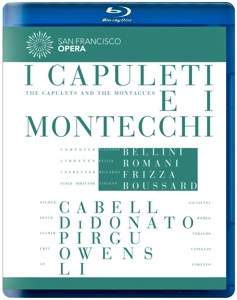

In a performance recorded live at San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House in October 2012, the assembled cast is mostly excellent. The chief reason to see this video is Joyce DiDonato’s strong performance as Romeo. Her voice has some built in limitations: a slender, reedy timbre and an intrusive vibrato that occasionally take the “bel” out of “bel canto.” What she has in spades is musicality and a natural feel for how this type of music should go. She knows when to sing a pure melodic line and when to ornament and trill away. She knows when to blend her voices with her colleagues and when to power through cabalettas. There are many singers who have a more conventionally beautiful voice than Joyce, but I can’t think of a singer who has more expertise in baroque and primo ottocento music and sings this kind of music with more care.

Nicole Cabell (Giulietta) was a soprano that was heavily promoted as the “next big thing” for a few years ago before the buzz tapered off. She has a very fine lyric soprano—it has a charmingly bright, fluttery sound that made an impact in “Oh! Quante volte” and her voice blended well with DiDonato in the duets. Decent coloratura skills too, although Bellini’s Giulietta is not really about coloratura fireworks. This is not going to sound very PC but I think that Cabell simply doesn’t have the looks for the kind of roles she sings. Her exotic, mature face looks like a natural Carmen or Dalila but she has the voice of a Gilda.

The seemingly ubiquitous Saimur Pirgu pops up as Tebaldo. It’s is not a very central role but I can’t for the life of me figure out why he’s in every opera video I see. He’s got an unremarkable, serviceable voice with a cute face. Eric Owens is a great singer but I don’t think Bellini is his thing—voice is too rough-grained, more of a Wagnerian dramatic bass-baritone than a basso cantante. Ao Li rounds out the cast as Doctor Lorenzo. Ricardo Frizza is another conductor whose ubiquity defies logic. I heard him drag La Bohème until it became as lifeless as Mimì’s body. He gives Bellini’s score the same listless, tired feel.

Vincent Broussard’s production and Christian Lacroix’s costumes seem designed to give some edge to the occasionally drippy music. A bunch of horse saddles hang from the ceiling of the stage. A dark, monochromatic color pallette is favored for all the “men’s” scenes. Romeo is a tough gang-leader type—we know that from his baggy cargo pants, black leather jacket, and army boots. DiDonato is aso wearing her generically wavy long-haired trouser role wig. Giulietta is portrayed as “bel canto mad”—her chambers look vaguely blood-stained and she spends a lot of time in her undergarments and on top of a sink.

The issue with this sort of regie-lite production is that it strives to look different but has nothing to say beyond the different look. Whatever you want to think of directors like Calixto Bieito, Peter Sellars or Stefan Herheim, they carry their concept throughout the opera with a relentless consistency. Broussard just presents different-looking stage pictures without any underlying concept. Seriously, if you’re going to do this, it’s better to bring back David McVicar and his pillars.

Comments