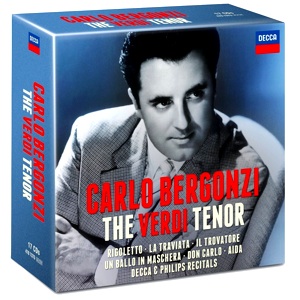

A great man has passed and our consolation is that so much of his art has been preserved for us on recordings. This year marked Carlo Bergonzi’s 90 birthday and next week, in honor of that occasion, Decca is releasing a box set

of 17 discs titled The Verdi Tenor, comprised of all of the Verdi opera and recital recordings Bergonzi made for Deutsche Grammophon, Decca and Phillps combined. It also includes his milestone traversal of nearly every tenor aria in the Verdi canon under the baton of Nello Santi. In memoriam now it also serves as archive to this supremely gifted musician who was an aristocrat among tenors.

His fundamental attributes were a warm, masculine, timbre coupled with an effortless expanse of phrasing that seemed to give the impression of more breath in reserve. He knew his way around an “oo” vowel and wasn’t afraid to use a glottal stop for emphasis if he felt the effect warranted. He generally kept the bottom of the voice light and almost always utilized a portamento to reach above the staff. All of these things in combination, to say nothing of his understated gifts as an interpreter, allowed him to retain his youthful sound well into his later years.

In 2012 when we were all celebrating the Verdi centenary Warner Classics went about remastering and re-releasing all of the Cetra recordings from the 1950’s. I know people who cut their teeth on these warhorses and have hardly been able to stomach the homogenized productions the record companies have served up since. Made in an era when opera was not only fiercely nationalistic but singers prized themselves on their individuality.

In 1951 the 27 year-old Bergonzi had just made the transition from baritone to tenor with his debut as Andrea Chenier in Bari. Someone at Radio Italia heard about him and shortly thereafter he had a contract to sing the tenor roles in Giovanna D’Arco, Simon Boccanegra and I Due Foscari for the RAI. All before the end a year that also saw his theatrical debuts in Pagliacci, Un Ballo in Maschera, La Forza del Destino and Adriana Lecouvreur. (We’re lucky nowadays if we get one new role out of a celebrated singer every other season!)

The I Due Foscariis especially compelling because it finds the tenor under the youthful, but already experienced, baton of Carlo Maria Giulini. The performance is nearly uncut, though the soprano, Maria Vitale, is fortunately being spared the majority of her opening aria. She’s a little overzealous in the Caniglia style. Bergonzi sings with an uncommon brashness and sounds. most appropriately, like a man who’s begging to be let out of prison. Perhaps there’s a little too much piangere in his big aria. Gian Giacomo Guelfi makes a stolid and considered Doge and the mono sound has been polished clean but is only flattering at the lower decibel levels. It’s well worth the addition to anyone’s collection.

Another underrated recording Bergonzi participates in is a wildly fascinating Rigoletto from La Scala conducted by the very individual Rafael Kubelik. Our tenor is joined by the then just 30 year old Renata Scotto as Gilda and, most controversially, by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Verdi’s accursed court jester. Kind of a Stimm, Stimm/Kunst, Kunst lineup of talent, this cast seems to try harder because they know they’re entering what is already a very full playing field in the catalogue.

Scotto is laser-sharp at times with stunning staccatos and it’s 1964 so the voice is still leggiero with a healthy top and very little of the wiriness that beset her later. She’s super scrupulous with dynamics, as one would expect, and, as always, dedicated to the beauty of the language. She also pops out a ripping good e-flat in alt at the end of the “Vendetta” duet.

Fischer-Dieskau is an anomaly; a thinking man in a role that mostly requires voice, voice and more voice. Sure he does a good deal of declamation rather than Italian style cantabile but he is so dedicated and individual of utterance that, to me, it matters not.

The real star here is Kubelik in the pit, whom you wouldn’t necessarily consider a natural Verdian. His use of rubato is almost preternatural and he is constantly gifting his singers with these gorgeous moments of grace within their parts. He’s also not in the least bit afraid to completely stop the orchestra, mid phrase mind you, to allow his soloists a stylish turn. Bergonzi benefits from this approach greatly as do we the listener.

They also make some very vivid and interesting choices in cadenza and our tenor ends “Parmi veder” with an impossibly long variant that would have required at least two breaths and an oxygen mask from a mere mortal. He also sings the cleanest and most stylish ‘La donna é mobile’ I’ve ever heard.

This Rigoletto is part of the Verdi box set mentioned above but it can also be got on the cheap on its own.

Two more recent releases are part of Verdi at the Met set. First is the Macbeth from 1959 and it was the Metropolitan Opera’s first. We all know the story about Maria Callas being fired by Rudolf Bing and hiring Leonie Rysanek to replace her. It was a canny decision. She’s a bucking bronco in the role and the voice, to say nothing of her support, are all over the place. She has no fioratura facility to speak of but a whacking good high C at the beginning of the ensemble that ends Act I. Her sleepwalking scene is a magnificent fil de voce.

Leonard Warren is revelatory in this role. His velvety legato just spinning out. Real acting with the voice and he and Rysanek are gripping in the Act I love duet ‘Fatal mia donna’. Not surprisingly they are both more vivid here than on the RCA recording that followed. Luxury casting features Bergonzi as Macduff, magnificent in the aria and especially the cabaletta/duet later with tenor WIlliam Ovis.

Erich Leinsdorf was a late replacement for Dimitri Mitropoulos who had suffered a heart attack. He’s a veritable man possessed with this score and by the time we get to the banquet scene he and the orchestra and chorus are on fire. Textually there’s a lot missing from this musical edition, quite a few repeats, the ballet, but what’s here is “cherce,” as they say and an interesting comparison to the studio set.

The other inclusion in the Verdi box is a Thomas Schippers-led Aida with a golden age cast dating from 1967. Bergonzi’s Radames here is a singing lesson. He attempts a piano messa di voce on the B-flat at the end of “Celeste Aida,” nearly comes to grief, adjusts and makes a save. He rings out like crazy during the temple scene and at the finale of the Nile act his “Io resto a te” is absolutely epic. Every line he sings has an interpretive thought behind it.

Grace Bumbry gets applause at her entrance and proves almost immediately why she deserves it. She lays down the Verdi law every time she opens her mouth. Her involvement is so intense she ends up throwing, what can only be termed as, a gospel scream into the judgement scene to remind anyone who didn’t know that she was a pupil of Lotte Lehmann.

Leontyne Price is in vintage 1967 form, when the top of that voice still had that precious vulnerability and juice. At the end of the Nile scene she spins out the most ravishing pearl on “fuggiam” it’s almost worth the whole set. During the jealousy duet you can figuratively hear the locking of horns. It’s a healthy competition.

Then Robert Merrill shows up and you’d think you’d died and gone to heaven in Bussetto. Even if his Italian betrays an American accent at times the sound is so full and the plangency so magnificent. There’s even this snarl in his voice at times that literally took my breath away. I need to add that Jerome Hines holds down the front for the basses on both of these recordings as Banquo and then Ramfis and he defines stentorian. His Banquo is particularly moving in his Act II scena.

Schippers takes an odd ritard here and there for emphasis and I’ll let him.The ballet in the Triumphal Scene is accompanied at times by a fearsome jangle of wooden beads which brings to mind a Cecil B. DeMille epic. The orchestra and the chorus aren’t as inspired as the Macbeth but, then again, performances of Aida at this level of competency at the Met were fairly commonplace at the time.

My last inclusion here is my most favorite and it’s a duet album on the Orfeo label made in July of 1982 when Bergonzi and Fischer-Dieskau met in the recording studio for the third and final time. The two Forza duets, Pearl Fishers, La Gioconda, La Boheme all get loving treatment from two gentlemen who were, I believe, both 58 years old at the time. You’re constantly amazed at how well they’re singing. Not that they can compete with their younger selves but it was a fine Indian summer for them. “Si, per ciel” from Otello finds Bergonzi mining real metal in the voice and the Don Carlo friendship duet gets a exquisite piano reprise.

I hope that at least some of you were intrigued by the selections here and seek out these fine recordings. I promise their pleasures will be many. Viva Bergonzi!

Comments