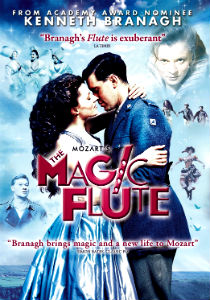

I’ve long been a fan of Kenneth Branagh, even though this fandom feels a bit like being a camel in the desert. At the ridiculously young age of 29 he directed and starred in what I consider to be the most rousing screen adaptation of Shakespeare’s Henry V. But from there on it’s been a bumpy road.

For every gem like the pants-wetting, backstage hilarity of A Midwinter’s Tale there are two duds at least. Don’t get me started on the monstrously overblown Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or the pull-the-rug-out-from-under-you nonsense of Dead Again. He’s at his best when he’s working with Shakespeare as evidenced by his most excellent Much Ado About Nothing but, even then, did we need every single line of Hamlet and did the cast of Love’s Labour’s Lost really need to warble Gershwin standards?

The mystery here is how his very imaginative film version of Mozart’s The Magic Flute got lost on its way to the multiplex. Having made the film festival rounds back in 2006 when it was fresh and received a limited release in Europe it never did get distribution in the U.S. until now. Finally having seen it in full we won’t be needing to call in Hercule Poirot to divine why.

In spite of the best efforts of a very elite group that include Bergman, Zeffirelli, Syberberg, Losey, and Powell & Pressburger, film and opera have never really meshed. The only director I think who came close to capturing the real magic was Jean-Pierre Ponnelle. His ingenious use of the camera like an objective proscenium evoked aspects of the theatrical experience that made his productions unique to their format.

Like so many great masterpieces Mozart’s evergreen score practically defies staging because it touches on so many themes it’s hard for an impresario to hold to any one concept. Often times in the theater the Flute just gets positively weighted down by the vision of some grand artiste dabbling in opera. Which is a lot like what happens here.

A year before War Horse at the National Theatre in London, Branagh hit on World War I setting for Flute, with Tamino as a young soldier. The concept works mostly in the beginning before you can start asking a lot of obvious questions. It works best when the Queen of the Night (Lyubov Petrova) makes her first entrance on a British Mark V tank. Genius. The Three Ladies shape-shift throughout as nuns, nurses, lady corporals, whatever contrivance is necessary at the plot point, which is clever.

Papageno is still a bird catcher, although now employed by the military to provide canaries for nerve gas detection. The Quintet (no.5) between the Ladies and Papageno and Tamino is set during the famous Christmas Truce of 1914.

Rene Pape’s Sarastro is the head of a field hospital in a converted castle and he also sings the lines of the Speaker. I don’t think there’s really any reference left to the Freemasons.

Branagh is brimming with ideas but, unfortunately, many of them tend not to coalesce with the wartime backdrop. A brigade of violinists marching into battle during the overture is a stunning visual coup but the butterfly the camera’s also following through the trenches is Hallmark Card smarmy. Other hits are the inventive touch of having the sandbags in said trenches morph into faces to sing the roles of the two armoured men and the nightmarish rendition of the Queen’s second aria.

Everyone does their own singing which is admirable and as it should be. The Tamino of Joseph Kaiser is particularly fine in both voice and presentation. He’s got the slightly dim but guileless affect down cold and his slim tenor is unaffected. The Papageno of Benjamin Jay Davis is mostly a Broadway baritone with the occasional foray into opera (Baz Luhrmann’s Boheme) and he does a commendable job even if he is laying on the ingenuousness with a trowel.

Sadly, outside of Pape’s Sarastro and Petrova’s aforementioned sub-machine Queen, neither of which require my endorsement, I wouldn’t call any of these singers particularly distinguished in their roles. The Pamina of Amy Carson is a downright liability. Although she’s exceedingly pretty of face the voice is almost completely blanched and sports a top so brittle with straight tone it can only mean tea and biscuits will be served shortly.

Production design by Tim Harvey is imaginative, utilizing some charming forced perspective work to hide the fact that we’re complete studio bound. Meanwhile Roger Lanser’s cinematography does an excellent job of keeping everything looking far more lush and detailed than I’m certain the budget could afford. A veritable CGI army of digital artists, compositors and matte effects workers is listed on the final credits and responsible for what, I’m sorry to say, is some seriously substandard work that appears at times like a fuzzy video game from 20 years ago.

James Conlon leads the Chamber Orchestra of Europe in a businesslike reading of the score that maybe could have drawn attention to itself a bit more since the visual element is almost always stronger. Even with a cast this youthful it’s near to impossible to avoid the musical aspect sounding canned. It is sung in English, which isn’t a crime with the Flute, and not surprisingly, the Sir Peter Moores Foundation is listed among the production credits.

Sound effects are kept to a realistic minimum although we do have the notorious “voice over” effect at times when characters are emoting within close range.

The best news about this Flute is that it’s available for streaming from Netflix (and Amazon Instant Video.) The DVD screener I saw looked to be just about the same quality on my monitor when I compared the two versions.

Comments