Before there was a Stefan Herheim Boheme (which I reviewed a couple of weeks back for this site), there was a Herheim Eugene Onegin, recorded in June 2011 at De Nederlanse Opera and released on DVD

and Blu-ray

by Opus Arte. As the Boheme might be described as “Rodolfo’s Dream”, this Onegin is “Onegin’s Flashback.” Herheim weaves his directorial magic by setting the opera in three different “time zones”—the here and now, the period of the opera’s composition, and the historical context of the Pushkin verse novel on which it is based.

Tchaikovsky’s lushly romantic opera (1881 revised version) follows the story of the naïve Tatyana who writes a love letter to Onegin, only to be rebuffed and lectured about being so careless with her feelings. Onegin wanders for eight years, searching for happiness and fulfillment, then, when he encounters the regal Tatyana who has become the wife of Prince Gremin, desperately tries to win her to no avail.

In this production, we begin in an elegant Moscow hotel in today’s times with gowned and tuxedoed guests emerging from an elevator and moving to to the entrance doors to an elegant ball given by Prince Gremin. Onegin suddenly emerges, having returned from his wanderings. He sees the red-gowned Tatyana on the arm of her Prince, and begins to wonder how this all began; we are then transported to the first scene of the opera with Madame Larin and Filipyevna talking about life in “the good old days.”

From this time on, Onegin rarely leaves the stage. He observes all the past events of his cold and callous youth, frequently enters into the action as if a participant, and tries to put together the story of his life through Herheim’s fascinating visual world.

The director also makes the production a comment on the very essence of the Russian character. In the name day party scene, a Russian star hangs above the scene, then it burns itself away; and there appears the Russian bear, life-size and dancing, always reflecting the emotional world of the opera. He remains a force in the piece, especially in the most remarkable part of the production: the Ball Scene at Prince Gremin’s, where Herheim shows us nearly two centuries of specifically Russian images.

Through this scene pass Russian Orthodox priests, Cossacks, Hussars, 60’s Olympic gymnasts, peasant folk dancers, Odette-Odile and the Prince from Swan Lake (the dancer as the Prince flirts shamelessly with the mortified Onegin), even cosmonauts in full space suits and Communist soldiers, and, of course, the Bear. Andre de Jong’s choreography is witty, thrilling, and delightful. Onegin wins a huge laugh at the end of this brilliant tour de force when he turns to the audience and sings, “I’m bored even here…”

Tatyana’s letter scene is also drawn as a psychological battle between the naïve Tatyana’s passion for Onegin and her mature love for Prince Gremin. In this scene, the young Tatyana’s bedroom and writing desk occupy the main part of the staging, but always present is Prince Gremin in his bedroom on stage left. Tatyana is pulled in and out of writing the letter by Gremin’s sleeping presence. And, Onegin, in flashback, enters the room to watch Tatyana’s tormented writing, and then sits at her desk and writes the letter to her dictation!

It’s hard to describe the extraordinary dramatic impact of this staging. Throughout the performance, director Herheim evinces a childlike wonder in creating his images. There is nothing of the cynicism of some Regietheatre directors—Herheim is a remarkably imaginative director who nonetheless manages to create an overall framework that makes sense with the characters, the story, and the music.

He has a strong artistic partner in conductor Mariss Jansons, who leads a masterful performance from the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, drawing a powerfully emotional reading of the music without resorting to sentimental tricks. He clearly knows that Tchaikovsky’s score is fraught with emotion; orchestra and singers need not add more layers on top.The cast is remarkably fine. Krassimira Stoyanova sings with gorgeous tone and tosses off Tatyana’s passionate outbursts with ease and beauty. She also clearly understands and commits to Herheim’s staging. This Tatyana is torn between the present and the past, between Gremin and Onegin, between the various sides of her own personality. I’m sorry to say that she looks frumpy and matronly in Gesine Vollm’s costumes; in particular, her red ball gown that should be flattering, is poorly cut and only serves to emphasize her least attractive features. And yet her performance is beguiling and powerful.

In quite a coup de theatre, the handsome young bass Mikhail Petrenko is cast in the usually-an-older-man-thrilled-with-his-young-wife role of Prince Gremin. He is every bit Onegin’s equal in looks and style, and the Prince’s big last act aria about his finding joy with Tatyana is brilliantly and gracefully sung. Tenor Andrej Dunaev is very fine as the doomed poet Lensky, singing with a liquid, lovely tone and bringing depth of emotion without resorting to effects. His “Kuda, kuda…” is a model of poised singing.

I also quite enjoyed the ladies of the Larin household—Olga Savova was luxury casting as Madame Larin, and Nina Romanova was delightful as Tatyana’s aging nanny Filipyevna. Elena Maximova’s Olga bubbled with girlish charm and high spirits. There was no ragged singing from anyone in the cast; all these Russian voices are in remarkable shape.

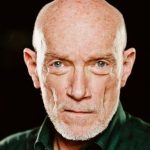

In the title role, Bo Skovhus was less successful. Perhaps because of the direction, he seemed stuck in playing the character’s confusion, and we never saw the dark side of the character’s personality. Even in lecturing Tatyana about her letter, he seemed unsure and too gentle. His singing was fine, if a bit lighter than I would have liked. He finally came into his own in the difficult final duet with Tatyana, but otherwise seemed too much “on the surface” of the role. There was, for me, a sense that he wasn’t quite buying into Herheim’s wilder ideas.

The superb sets were designed by Phillip Furhofer and, outside of the unflattering costumes for Tatyana, designer Vollm gave us inventive and stylish clothes. Lighting by Olaf Freese was vitally important in delineating time and place. The very game chorus of De Nederlandse Opera sang beautifully and acted/danced as if they were having a fine time. The audience certainly were!Herheim’s vision is certainly not universally loved. But he presents us with a unique and unified point of view that is highly theatrical but remarkable in its detail and inventiveness. I could watch that “Russian history lesson dance” at Prince Gremin’s ball ten times, and still see new things in it; in addition, it places the story in a clear perspective of the national character of Russia. And yet, Tchaikovsky’s personal torment, reflected in this magnificent music, is always present.